Flying East on Rockaway Beach

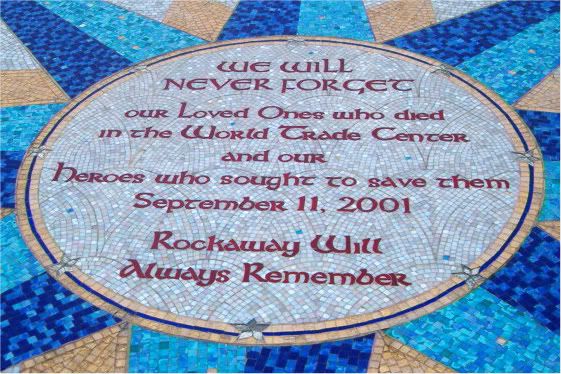

Each July the residents of Rockaway Beach open their homes to host Wounded Warriors –wounded service men and women and their families. Rockaway, home to many New York City firefighters and police officers and the families of those killed in the 9/11 terrorist attacks, honor the heroes who went to war for them with a parade, a street party, and a Catholic Mass at the Breezy Point 9/11 Memorial.The event begins when the Wounded Warriors ride into Rockaway on antique fire trucks, escorted by the NYPD, including NYPD choppers, and the FDNY. Traffic comes to a standstill just outside of Manhattan and the wounded warriors, flanked by New York City firefighters and police officers, ride through Brooklyn and Queens with hordes of people, including firefighters, waving and cheering them on. Overpasses along the route are filled with supporters, more fire trucks, and banners. Firefighters in dress uniform and work uniform stand in salute as the parade passes.

Then, after meeting their host families in Rockaway, the soldiers and their families prepare for four days of sailing, fishing, water-skiing, scuba diving and a dinner cruise in New York Harbor. Clearly, the event means more than a chance to learn to water ski and go fishing; it is a mix of recreational and spiritual therapy on the waves, a time for heroes of all breeds to come together to celebrate each other.

Hometown Heroes

It's one of the most enduring images we have of the September 11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. In the chaotic hours following the deadly assault, when the fear of further attacks was still extremely high and the fate of so many New Yorkers was still unknown, three city firefighters did something so simple, yet so extraordinary, considering the circumstances. They raised up an American flag that had been displaced among the wreckage and destruction around them.The photo that ran in various newspapers the day afterwards inspired New Yorkers and Americans still struggling to regain some sense after the inhumane attack, and that image will remain with them for years to come. It was so appropriate, and yet so bitterly ironic, that one of the firefighters in the picture - that fellow on the left - was George Johnson, a resident of Rockaway Beach.

Known mostly for its picturesque beaches and strong Irish American population, Rockaway has taken on a grisly infamy since the terrorist attacks. In terms of people missing and loss of life, it is among the hardest hit places in all of New York City - some reports have claimed as many as 70 Rockaway residents, many of them firefighters, were either confirmed dead or still unaccounted for.

There are few places in New York City that have the type of community spirit that Rockaway has, and much of it is drawn from an Irish American heritage that means so much to so many of its residents. There are so many stories of people missing or dead, all of them heartbreaking in one way or another.

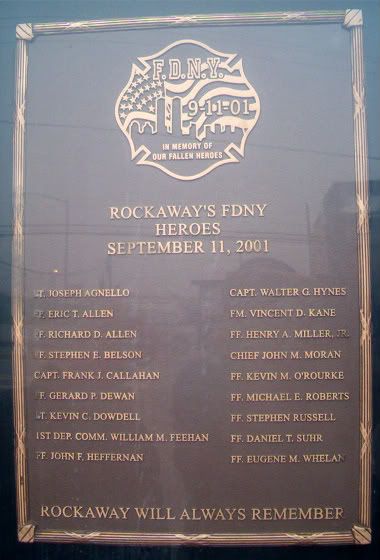

Joey Agnello, Lieutenant Ladder 118

On the morning of September 11th, Agnello and 5 of his fellow firefighters aboard Ladder 118 responded to what was to become their final fire. They parked their rig at West and Vesey Street by the towers and vanished into the thick cloudy smoke and soot of the Marriott World Trade Center Hotel. Accounts by those rescued speak of the Ladder 118 crew ushering hundreds of the building occupants to safety. Survivor Bobby Graff says, "Their families should be proud of them. They knew what was going on, and they went down with their ship. They weren't going to leave until everyone got out. They must have saved a couple hundred people that day. I know they saved my life." Graff recalls, "Joey helped me bring handicapped people down from the 19th floor in the elevator. We then went up to the 12th floor where people were screaming and brought them down. Then the mayday call came on the radio and the command was 'Get out! Get out! Get out!'. Joey and the other guys used their bodies like a brace - like a riot squad - directing the people out. They knew what was coming, but they stayed where they were. I'll never forget that." The men of Ladder 118 died side by side. A simple man, Joey, 35, never looked for credit for his accomplishments, nor wanted for material possessions. He found comfort and happiness in the little things: being with his family and looking up at the sky on a starry night. "Sometimes, when I take the dogs to the beach for a walk and I look up, I know he's still around," his wife said. "Like tonight. There's the most beautiful moon, and I know he's with me."

Eric Allen was diligent, determined and headstrong. He was so tough, so capable, that it would never occur to people to look down on him, a 5-foot-5 tower of gym-rat power. He knew how to size up potential trouble quickly and dodge it adroitly. Once, while driving cross-country with his buddy Joe Ruggiero, the two walked into a bar on the Texas-Oklahoma border and, in the blinding daylight, saw half a dozen oversized cowboys playing dominoes. "Drinks for everyone on us!" shouted Eric, buying a barfull of friends. The short guy cast a long shadow: Eric, 44, was a ubiquitous, modest Mr. Fix-It for friends and the elderly in the neighborhood. His motto was "Do the right thing," which for him meant taking extra courses to be eligible for the hazardous duties of Rescue Squad 18 of Manhattan. He was a sweetie with a crust, a shy man who loved acting. As he drove on jaunts to the country with his wife, Angelica and their 3-year-old, Kathleen he would make up songs about how much he loved them, yelping happily.

Richie Allen, Firefighter Ladder 15

Summer after summer, Richie stood watch along the beaches of the Rockaways, keeping swimmers out of danger. He had his share of ocean rescues, and then there was the one he pulled off on dry land, after a couple of people dug a giant hole in the sand that then collapsed around them. When he was not in the tall lifeguard's chair himself, he was never very far away. He'd create a hammock by tying a sheet to the supports beneath the chair and rest there awhile, enjoying the breeze blowing and the gulls calling and the pace of one more nice warm day. He was the much-adored oldest of six children, and his siblings trailed him into lifeguarding. "Growing up in Rockaway, if you can swim, then that's the best job to have," said Judy, one of his sisters. He got other jobs — substitute teacher, sanitation worker — before the Fire Department called him to work in May of 2001, when he was 31. He spent seven weeks with Engine Company 4 in Lower Manhattan, and then moved to Ladder Company 15 in the same firehouse. On Sept. 11, he rode with the engine company to the World Trade Center, even though he was off duty after having worked all night. The Sunday before, he and his mother, father, sisters and brothers had all spent the day together on the beach. And they realized that their lifeguard had become a firefighter. "He said how much he absolutely loved the job," said his mother, Gail. "It was part of his breathing, almost. He was saying he couldn't wait for his first fire." Beach 91 Street has been named, "Richie Allen’s Way.

Stephen Belson, Firefighter Ladder 24

Stephen E. Belson, 51, had different nicknames from different stages of his life. At Rockaway Beach, where he worked after college as a lifeguard, he was known as "Bells". But at the fire station on West 31st Street in Manhattan where he spent most of his career as a firefighter, he was given the title ''Mr. Ladder 24.'' ''He was our ambassador, so to speak,'' said John Montani, another firefighter in Ladder Company 24. Firefighter Belson attended all the functions, was always available for holiday duty and could back a fire engine into a station in five seconds flat. His last job was as a driver for one of the battalion chiefs, Orio J. Palmer. Both rushed to the World Trade Center on Sept. 11; neither returned. Before he joined the department, Firefighter Belson was something of a beach bum, a surfer, a devotee of the Grateful Dead and Hot Tuna, or as one friend said, a free spirit. Then, one day, he and his lifeguard buddies decided to get real jobs. Firefighter Belson who grew up in Flushing, Queens, moved to Rockaway Beach, bought a house and fit right into the tightknit community of firefighters and police officers. Unlike many of his neighbors, he wasn't Irish or Roman Catholic. But that made no difference. ''While he was Jewish, he was considered one of them,'' said his mother, Madeline Brandstadter. ''They even named Beach 92nd Street after him: Bells' Beach.'' His mother recalls the two most important pronouncements in her son's life "I love Rockaway and will never live anywhere else" and "I love the Fire Department and will never work anywhere else" ".

Frank Callahan, Captain, Ladder 35Frank Callahan, 50, was living his dream. As a boy and a young man he had wanted to be a firefighter. In 1970, when he met Angie Lang, the woman who would become his wife, at a party at a volunteer firehouse in Breezy Point, Queens, he had not yet attained that dream. "He was on the list," Mrs. Callahan recalled, referring to the men and women who had passed the written and physical tests to be firefighters and were waiting for the call. It came a few years after they met. Mr. Callahan was appointed in September 1973. "That job was all he ever wanted," Mrs. Callahan recalled. "That was the best thing that ever happened to him." In the years that followed, the couple had four children. Frank was promoted to captain in 1997 and months later was transferred to Ladder Company 35 on the Upper West Side, but the family did not have any big parties. "He wasn't big on celebrations," Mrs. Callahan said. A quiet man, Frank liked to read about the Civil War or World War II. "He'd rather sit and be home," said Mrs. Callahan. As the children grew, Mr. Callahan taught them how to ride bicycles and play basketball. But Mrs. Callahan's most cherished memory was when her husband and Harry, then not older than 5, worked together on the exterior of their house in Breezy Point, with Harry helping his father with the hammering. "He was his little helper; wherever Dad went, he went," Mrs. Callahan recalled. "He was very good with his kids that way."

Gerald Dewan, Firefighter Ladder 3

Gerard Dewan was only 35 years old on September 11, 2001. On that day, he and eleven others from Ladder Company 3 (Battalion 6) in Lower Manhattan were called to duty at the World Trade Center. He was one of the first rescuers to enter the twin towers, but he never made it out. He was born and rasied in Boston and came to Rockaway Beach to begin his career as an NYC firefighter in 1996. He was a 3rd generation firefighter, with 9 firefighters in his family, including his Grandfather and Dad, but there were no jobs openings in Boston at the time. The Gerard Dewan Memorial Fund was established to keep Gerard's memory alive and to honor his commitment to helping others.

Kevin Dowdell, Lieutenant Rescue 4

When Kevin's family moved to Colorado while he was still a child, he moved in with a sister in Rockaway Beach and graduated from Far Rockaway High School in 1972. He had worked various jobs in construction, including as a "sand-hog" or tunnel digger, before he got the call to join the New York City Police Department in 1980. A year later, Dowdell got a call from the New York Fire Department. He couldn't pass up the opportunity and left the NYPD. "He loved the fire department," his wife said. "It was really like a home away from home." A member of Rescue Co. 4 in Woodside, Lt. Kevin Dowdell, 47, is presumed dead in the terrorist attacks. Kevin's work ethic and other traits of his personality are evident in both of his sons. His living spirit carried one son, James, into the FDNY and another to West Point. Army 1st Lt. Patrick Dowdell, departed for Iraq on St. Patrick’s Day, 2007.

Willaim Feehan, First Deputy Commissioner

William Feehan was the Fire Department's second-highest official. His knowledge and cunning in battling fires made him the stuff of legend to his firefighters. When he was not fighting fires, Bill walked the fields of Gettysburg, toured Churchill's War Room and read naval history. Military culture, with its embrace of tradition and tactics, appealed to him, much the way firefighting did. He worked as a substitute teacher for several years, even after joining the Fire Department in 1959. He was first assigned to Ladder Company 3, and then to Ladder Companies 18 and 6, making him a truckie, as firefighters call those who serve in ladder companies. He also served in Engine Company 59, and in Rescue Company 1, a unit that suffered heavy casualties in the World Trade Center collapse. He fought many large fires, particularly in Harlem and Brooklyn in the 1960's. He battled the blaze that killed 12 firefighters in Madison Square in 1966, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard fire in 1960, which killed 50 people. He was named chief of department in 1991, making him the first person to hold every possible rank within the fire department. When he died, Commissioner Feehan, 71, was the oldest and highest-ranking firefighter ever to die in the line of duty.

John Heffernan, Firefighter Ladder 11

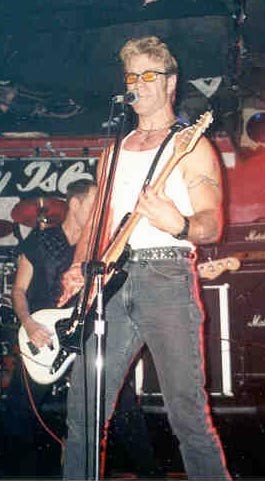

When John Heffernan died on Sept. 11, it robbed New York's punk community of one of its strongest creative forces. When he met The Bullys in 1998, Marky Ramone liked the band so much he produced their first album, Stomposition. Bandmates remember the charismatic redhead with "a map of Ireland and a few bar brawls" on his face. Heffernan, who ran his band's business and designed thebullys.com, wrote and produced the band's next album, We Fight Again; the title track an ode to his native Rockaway. Those were his streets, that's where he grew up, that's what he wrote about, Rockaway. "It's Still My Home" was an oath of blood loyalty, a Celtic warrior's do-or-die pledge to love and defend his turf. Hef, 37, was a New York firefighter since 1993. Beach 114th Street has been renamed Firefighter John Heffernan Street.

Walter Hynes, Captain Ladder 13

Walter G. Hynes, was a 32-year resident of Rockaway. He valiantly gave his life on the morning of September 11, 2001 while assisting victims of the World Trade Center attack. Walter worshipped at St. Francis De Sales and was the Captain of Ladder Company 13 for the New York City Fire Department. He was 46. Walter was a family man, as well as a jack of all trades. In addition to his job with the FDNY, he was also an attorney, and the co-owner of a restaurant in Rockaway Beach. Beach 93rd Street has been renamed in honor of Walter Hynes.

Vincent Kane, Fire Marshal Engine 22

Kane, 37, grew up in Breezy Point, Rockaway, Queens, where he became a volunteer fireman at 17. "He was always giving," Joan Kane, his mother, said. He loved to play tunes by the Grateful Dead or the Beatles on his guitar. He spent hours in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and went to performances of the New York Philharmonic . . . something that still amazes his friends in Engine Company 22. "Most firefighters don't even know what the Philharmonic is," said one of them, Michael Ruddick. Vinnie kept a guitar in his locker at the firehouse, too, and would sometimes announce to his colleagues that he was heading out to play it in the park. I used to tell him he was straying as far away from the normal firefighter stereotype as he possibly could, Ruddick said. He was also an environmentalist who regularly patrolled the firehouse trash bins for recyclables. And he became a vegetarian, though the other firefighters insisted on piling red meat onto his plate anyway. "My daughter would be serving turkey on a holiday, and he would have the artificial kind," said his mother. "We had to laugh when he'd do that."

Henry Miller, Jr, Ladder 105

With one exception, Henry Miller Jr., 51, made his way through life slowly, meticulously. He took maddeningly long to finish anything — woodworking, roofs, stories. His garage was a testament to the potential of broken objects, the dream of a thousand somedays when he would get around to fixing them. (Enduring mystery: just how old was that slice of pie found under the scuba gear and fishing tackle?) Yes, he took his time. Spent 28 years at the job. Countless hours giving pep talks to a woman who lived on the street; she would later credit him with her decision to get off welfare, find work, start a bank account. He was 45 before he married. And like all his projects, this one glowed: "I dunno, fellas," Mr. Miller would say to holdout bachelors, "marital bliss, it's the way to go!" He was a steady, gentle man, slow to anger, who covered his wife Diane and her children with a mantle of security. He understood the value of time and unwavering persistence: he beat back bladder cancer and smoke inhalation, too. What's the exceptional rush? Only to a fire: Henry Miller drove the truck for Ladder Company 105 in Brooklyn.

SURF WITH HENRY

John Moran, Battalion Chief Battalion 49

(Freeper BCM)

If God was interested in good company he found it in John Moran. John was truly a modern day Renaissance man. He displayed equally assets of physical and intellectual prowess, all wrapped up in true humility. Think of society's loss of an individual who dedicated his life to service in the form of fighting fires and saving lives. He answered the call for leadership by rising to the rank of Battalion Chief, enduring departmental exams for years and at the same time attaining a Juris Doctorate from Fordham University School of Law! An accomplished musician, John played bass guitar, guitar, piano, the Irish tin whistle, drums and I would imagine a few other instruments I am not aware of as well as singing. John Moran was an Irish Lion with a heart to match, he embodied so much that makes me proud to be an Irish-American, and his brother Mike did us all justice by plainly stating what we all felt. Beach 118th Street at Ocean Promenade has been renamed Chief John Moran Way.

The Ballard of Mike Moran by dougfromupland

Kevin O'Rourke, Rescue 2

All the kids knew. If their bike was broken — a flat tire, a loose chain — then all they had to do was take it to the firehouse and see Kevin M. O'Rourke. He would dig his tool kit out of his locker, where the other firefighters had taped up a sign saying "Kevin's Bike Shop," and he'd fix it. And while the kids were there, he invariably taught them fire safety. He would unroll a rug and demonstrate how to do the stop, drop and roll technique for when one's clothes caught fire. Firefighter O'Rourke, 44, lived with his wife, Maryann, and their daughters Corinne and Jamie. Each year, his family and his wife's family would converge for a ski trip and a golf outing. He also was a regular in the annual firefighter ski races at Hunter Mountain. There would be five-man teams, and they would be in their jackets and helmets and have to cling to a fire hose and swoop down the mountain. There were innumerable teams, but one year Firefighter O'Rourke's came in fifth, and it made him very proud.

Michael Roberts, Engine 214

6611. That was the number of Firefighter Robert Roberts's badge. When he left the job, the badge was assigned to his brother, John. When Firefighter John Roberts left the job, #6611 was passed on again, this time to John Roberts's son, Michael. #6611 was a Roberts family heirloom by then, but Michael Edward Roberts had a habit of misplacing things. So his mother, Veronica, urged him to think about putting the badge in a vault and getting "one of those fake ones" for everyday use. She need not have worried. In nearly four years as a firefighter, Michael never lost track of that badge. He was as conscientious a recruit as Lt. Michael Bell, an officer of Engine Company 214 in Brooklyn, had ever seen. Although Firefighter Roberts had transferred there only in March, Lieutenant Bell said, "We could tell he was going to be a star." Being a fireman was the center of his life, but Firefighter Roberts, 31, was more than that, said his uncle, Assistant Police Chief Joseph Fox. "He had a way of popping into and out of people's lives," Chief Fox said. Firefighter Roberts routinely volunteered to work holidays for colleagues at the firehouse who had families.

Stephen Russell, Firefighter Engine 55

Stephen P. Russell was a firefighter with Engine Co. 55 in Little Italy. Steve and his fellow firefighters were investigating a gas leak nearby on September 11, 2001. They rushed to the towers and joined other FDNY units in evacuating those moving down from the upper floors. They called him "MacGyver" at the firehouse. He could fix anything, and do anything that needed to be done. He worked wonders with wood. He was a member of the Carpenters Union. He was so skilled that he built his own furniture and many items for the firehouse as well. He had even built a display case which has now become a memorial to him and his four fellow firefighters who died at the World Trade Center. Steve was born and raised in Rockaway Beach and lived in his house on Jamaica Bay. Steve loved the water. He was a master scuba diver, a sailor, and an avid water-skier.

Danny Suhr, Firefighter Engine 216

Daniel Suhr sacrificed his life trying to rescue victims in the World Trade Center attack, but it was the efforts to save him once he was injured that ended up saving the lives of several city firefighters. Suhr, 37, was fatally injured when someone jumped from Tower Two and struck him. Seven firefighters, including four members of his Engine Co. 216 in Williamsburg, came to Suhr's aid. Minutes after Suhr was rushed to Bellevue Hospital, the tower came crashing down. Suhr and his colleagues would have been in that tower if he had not been injured. "We're alive because of Danny,” firefighter Tony Sanseviro said. "It was almost like he knew,” firefighter Chris Barry said. "He didn't look scared, but he knew it was bad.” Before Suhr died, the Rockaway native was the captain for the FDNY football team and the Brooklyn Mariners, a semi-pro team.

Eugene Whelan, Firefighter Engine 230

"He was no saint!" said Eugene Whelan's mother, Joan, her laughter bubbling up. "Yeah, he could be a giant pain!" her husband, Alfred, added, chuckling about the ninth of their 10 children. But examples eluded them. While Firefighter Whelan, 31, undoubtedly jettisoned saint eligibility at some Rockaway Beach pub or Grateful Dead concert — a captain called him "the king of fun" — he was still terrific. He kept extra winter jackets in his Jeep in case he spotted a shivering homeless person. He was a persistent serial hugger, spreading those burly embraces known as "Eugene hugs." He was a Mr. Fix-it and human Velcro to kids. In Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, the neighborhood served by Engine Company 230, children would arrive at the firehouse with broken bicycles for Firefighter Whelan to make whole. During a school visit, he asked why one child was left in the bus. The child was paralyzed, a teacher replied. Mr. Whelan carried the child to the fire truck. "He understood what life was really about," said his father, "so we feel pretty good about him." Beach 37 Street has been renamed "Firefighter Eugene Whelan Street".

And Two Very Special Non-Rockaway Friends

Timothy Stackpole, Captain Division 11

In the company of heroes, Stackpole’s story is one that stands out from the pack. He was first recognized for his heroism after surviving an East New York inferno in 1998 that killed two firefighters. He and four other firefighters had raced into the building, mistakenly believing that an elderly woman was trapped within. The floor gave way, killing two of his fellow firefighters. Stackpole of Brooklyn, NY was left critically injured. Stackpole underwent a heroic recovery and joked from his hospital bed that because of the injury he’d have to retire after 40 years on the job instead of 50. This despite the fact that his severe injuries would have qualified him to retire with a full pension. He underwent years of rehabilitation, dozens of surgeries and painful skin grafts. He made it back to active duty, promoted to captain at Division 11 in Downtown Brooklyn just days before he died. On Sept. 11, Stackpole formed a company that rushed into the South Tower shortly before it collapsed.

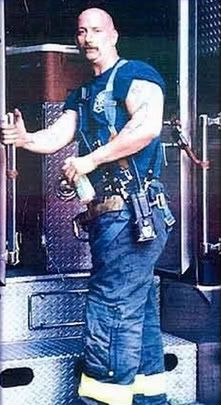

David M. Weiss, Firefighter Rescue 1

Firefighter David Weiss, 41, was declared missing on September 11, 2001. Born and raised in Freeport, NY, he joined the Freeport Volunteer Fire Department in 1978 and the Iron Workers Local 580 in New York City. He was appointed to FDNY in 1989 and became a member of Manhattan's elite Rescue Company 1 after receiving the Emily Trevor-Mary B. Warren Medal for a daring rescue of a man. A car had plunged into the East River from the FDR Drive. David, off duty, was also on the FDR Drive. He stopped his car and climbed down the iron trestles of the elevated highway and jumped into the river to save the driver. In addition David was a recipient of various awards including Firefighters Quarterly Man of the Year 1993, Firehouse Magazine Heroism Award and a NYC Transit Award.The men of Rescue 1 are specialists, called in to fight the unusual fires, free trapped firefighters, and save lives. They were heroes long before Sept. 11th. During the summer of 2001, a television show called "The Bravest" shot almost 100 hours of tape, capturing everyday acts of courage by the men of Rescue 1. "Lots of heroic deeds are done here. Lots of heroic stuff that’s never said. More heroic than anything you can imagine," said David on one of those tapes. "I was born for fire fighting. I’m a legend. Ever since I was a kid, I knew what I wanted to do. Organized chaos is a fire situation and you can’t beat the action in Manhattan. The emergency work. The fires. The buildings. You don’t find this anywhere in the world."

David could be described as all muscle and heart, standing at five-foot, nine inches and weighing in at two hundred and twenty-five pounds. His tattooed-covered body was one that, if you needed to be rescued, you wanted it to be someone like him. He was a fun-loving man who had a extraordinary zest for life and he rode a Harley. David’s body was never recovered and a memorial service was held for him on September 30, 2001

Rest In Peace, Brothers