Posted on 07/05/2014 4:40:26 AM PDT by Kaslin

Before he was America’s first president, George Washington was a spy and a soldier, serving on America’s frontier. His spying activities in advance of the French and Indian War brought him a national reputation and helped precipitate that great war. The reputation he built then secured a military command for him in that war which would eventually lead to international acclaim as America’s first commander-in-chief.

In the year of 1753, French soldiers marched south from Canada into an area where claims of sovereignty between France and England were in dispute. This area is roughly where Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania is now located at the forks of the Ohio and Allegheny rivers. The French soldiers brought with them Native American warriors and together they harassed, captured and killed English, Dutch and German settlers in order to scare them into leaving the area in order to claim the land for France.

The governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, chose 21 year-old George Washington to trek 400 miles into the frontier to deliver to the French a demand to leave the disputed area or face the prospect of war with colonial America and England. Washington also went to gather intelligence on the way, as there was little doubt that England and America hoped to pick a fight as much as the French did.

We know quite a lot about what happened on this expedition because Washington kept a diary that was later published.

According to the diary, Washington took with him Jacob Braum, his fencing master, and two Native American scouts lent to him by Half King, America‘s Native American ally plus he "engaged Mr. Gist to pilot us out, and also hired four others as Servitors, Barnaby Currin, and John MacQuire, Indian Traders, Henry Steward, and William Jenkins, and in Company with those Persons, left the Inhabitants the Day following."

They plunged into the wilderness, taking notes about the country, and how best to defend it. Washington was very familiar with this area. He had been traveling these roads on business for years. He owned a great deal of land in the area, like many of the pro-war party in Virginia. He accumulated the land by acting as a frontier surveyor.

After weeks in the wilderness and often sleeping with no cover on the hard ground, Washington made contact with a party of French soldiers as winter was coming on. The soldiers took him to the fort that the French had recently built near the forks of the Ohio and Allegheny rivers. The commander of the French forces in the area was named Monsieur Tissot. Washington told Tissot that he was on a diplomatic mission and that he had a communication from the royal governor of Virginia. Monsieur Tissot read the letter from Governor Dinwiddie but said that a reply would be a long time coming as he needed to send the letter to his master in Quebec, says Washington.

In the meantime, the French entertained Washington and his party with elaborate courtesy, holding feasts and parties in their honor. Washington was given freedom to inspect the French fort and made notes about its weapons and design.

Finally after weeks of waiting, with snow beginning to accumulate on the ground, George was given the bad news: the French had no intention of leaving the area. This meant war.

Washington was impatient to leave the fort, although it meant braving icy temperatures and ice-clogged rivers for the 400 mile return trip to Williamsburg, the capital of colonial Virginia. Waiting until the weather warmed would allow the French to have months to prepare for the spring and fighting; and the Virginians might be attacked by surprise.

Equipped with a pair of snowshoes, Washington says he left the French fort accompanied by his guide, Christpher Gist, and two Native American scouts friendly to the French.

Shortly into their journey, one of the native scouts fired at Washington and Gist with a musket but the bullet missed its target. They chased him away, but they took the other scout prisoner until they could put many miles between themselves and the prisoner’s friend. When they were safely away, they released the scout unharmed, records Washington in his journal account.

Washington and Gist then traveled quickly, worrying hostile natives might be all around them.

Using hatchets, they spent an entire day fashioning a raft to cross an ice-choked river. As they crossed, they used poles to push the raft across, and to avoid the ice chunks in the river. Unfortunately their homemade raft was no match for the ice. One chunk after another bombarded the raft until both Washington and Gist were forced overboard. They swam safely to a small island in the middle of the river. They spent the night in frozen clothes sleeping on the ground. The temperature dropped so low that in the morning that they were able to walk safely across the frozen river and shortly thereafter arrived in the colonial capital.

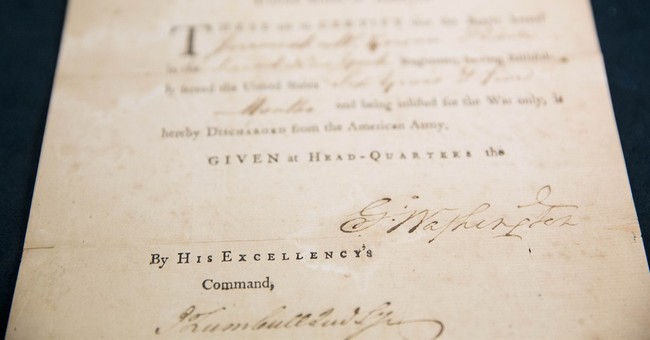

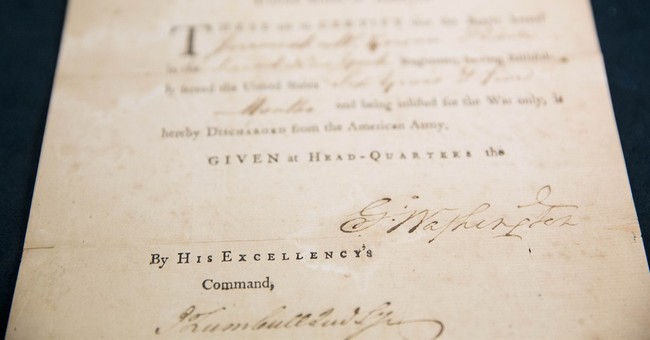

The colonial legislature in Virginia (the House of Burgesses) after reading Washington’s own account of his adventures, voted to raise an army to confront the French, and if necessary fight them. Because of his distinguished service as a diplomat-spy, Washington was selected as the second in command of the Virginia army.

Much of Washington’s military philosophy was formed during the French and Indian War. Just as in the Revolutionary War, Washington faced a foe that enjoyed numerical superiority, at least in men-in-arms. Washington therefore concentrated on keeping his force as a “force in being” and started to develop an appreciation of how intelligence could be used to even the odds against a numerically (and sometimes materially) superior foe.

This is in part because his record of command had a very shaky start.

Washington took about 400 troops into the wilderness, and despite being greatly outnumbered in total, decided to pick a fight with a small French advance contingent even though technically England and France were not at war.

After surprising and overwhelming the French advance guard, Washington retreated to his main camp, called Fort Necessity, a rickety compound of upended logs dug into the shallow earth, with the appearance of a ten-foot privacy fence.

Here the French soon approached with a force that was both numerically superior and materially superior.

The fort was poorly situated in a clearing that was too near to the forest. The forest gave the French cover while Fort Necessity offered only American soldiers a mud hole while it rained on them steadily. Much of the powder Washington had in the fort was spoiled from the wet. In an eight hour battle, the French finally compelled Washington to surrender the fort under terms that narrowly allowed him to avert total humiliation, although they were humiliating enough. Half-King, ostensibly Washington’s ally, mocked him by calling the fort “that little thing upon the meadow.”

The next day, Washington marched out of Fort Necessity and surrendered the fort to the French. The French promptly burned it to the ground.

The date was the 4th of July, 1754.

But the date that became important for Washington to celebrate in future years was July 3rd, not the 4th. And not because that was the day the Declaration of Independence was actually signed. It was approved on July 4th, and signed at later dates.

As historian Fred Anderson notes: “Indeed, in a letter Washington wrote on July 20, 1776, as he awaited the British invasion of New York, he made no mention of the independence proclaimed two weeks earlier, but noted only his ‘grateful remembrance’ of ‘escape’ at the battle of Fort Necessity on July 3, 1754.”

There are a number of great firsthand accounts of George Washington during the French and Indian War, but I highly recommend Anderson’s The War That Made America and George Washington: A Life by Willard Sterne Randall. Randall’s is an especially absorbing, complete biography of a great man.

The date of Independence Day is whatever the Founding Fathers decided to make it. Maybe they liked the number 4 more than 3. If it were up to me, I would made the day we were finally free, October 19, 1781 as Independence Day.

GW wasn’t the BEST military man but he was steadfast determined and above all HONORABLE in word and deed for his entire life.

I am convinced that this country would never have become what it is without him.

I have stood before his tomb and begged him to return. We need him again.

Amazing to think the French (Rochambeau and Admiral de Grasse) collaborated with Washington in 1781 to defeat the British in Yorktown.

I like to tell folks that if Washington had not defeated Lord Cornwallis that October we would still be speaking English in this country.

A spy? Can’t believe nobody recognized him!

Well, that's one way of putting it.

From the French POV, Washington attacked and murdered a diplomatic party, quite in contrast with his reception the year before while on a similar mission.

Yorktown really wasn't all that decisive. The British southern strategy had already failed, like all their other initiatives. They could march through the country, but the patriots closed in behind them, and they accomplished exactly nothing.

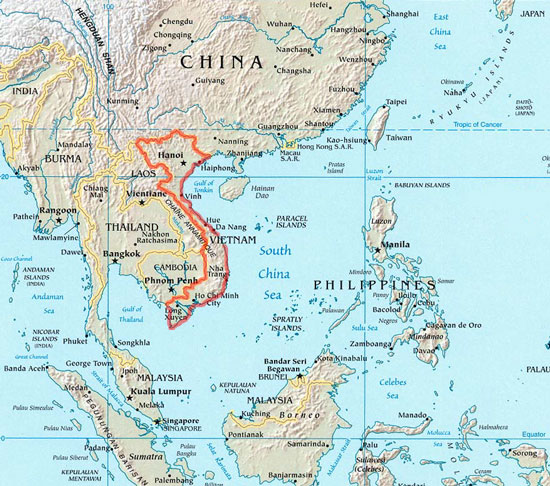

Sooner or later the futility of their attempts to reconquer America would become obvious to them. The British had to win, the colonists only had to keep from losing, a much easier task. As we learned in Vietnam.

For some reason, the date independence is declared is always the day people observe, rather than the date independence is achieved.

If the founders had picked July 3, my father (RIP) would've been a Yankee Doodle Dandy - but my neighbor (a retired surgeon; you too RIP) wouldn't have been. Neither would have Calvin Coolidge or The Boss in the Bronx. (Sorry, I haven't read this whole thread yet)

ff

True enough, but I live here so I joke.

"Sooner or later the futility of their attempts to reconquer America would become obvious to them."

The war of 1812 was part deux of the Revolutionary war so they were still unconvinced and managed to burn down DC. You're right that the effort was doomed (too much territory, supply lines too stretched, out much like Napoleon in Russia) but they were still trying. My post was more to the shifting alliances and interests of the French and how they related to the efforts of the colonists.

As to Vietnam, we didn't fight to win. We were trying to keep the communist from moving south and controlling the shipping lanes. It was a defensive action more than an attempt to conquer. The object was to preserve the strategic lines of communication and transportation. (Much like Korea and the first gulf war we fought a, "holding pattern" rather than to achieve victory.) The politicians weren't trying to "win" which is why we "lost". The public was lost in the long war without understanding why the South China Sea was strategic enough to protect.

Agree.

Except I just finished a book on the War of 1812, and I don’t think it’s really fair to call it Revolution II.

The Brits were perfectly well aware they could not possibly reconquer USA. What they thought they could do, however, was chop off pieces, such as be moving the northern border south so that Canada included all the Lakes. They also thought they could assemble an Indian Nation as a buffer state in the northwest, and possibly in the southwest. They possibly even thought they could take New Orleans and force the USA back beyond the Mississippi.

All of these notions were delusional, of course. The massive population explosion underway in the USA and its resultant expansion westward could not at this point in time be stopped by the British, or for that matter by the US government.

As for the burning of Washington, that was an truly shameful episode in American history. The British force involved was really just a raiding party, and either MD or VA had more than sufficient militia available to stop the march on DC. But astonishing incompetence on the part of the American and state governments allowed the defeat to occur.

The American performance in the war was amazingly mixed. Incredible incompetence and cowardice and then the reverse.

The American Navy for the most part performed prodigies. The Army, not so much, especially in the first year or so.

Jackson’s defense of New Orleans against a much superior British force was a truly great victory. One of the worst British defeats of the 19th century.

The war didn’t end with victory at Yorktown.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.