Posted on 08/20/2010 9:51:07 AM PDT by Daffynition

When I think about the rules of grammar I sometimes recall the story—and it’s a true one—about a lecture given in the 1950s by an eminent British philosopher of language. He remarked that in some languages two negatives make a positive, but in no language do two positives make a negative. A voice from the back of the room piped up, “Yeah, yeah.”

Don’t we all sometimes feel like that voice from the back of the room? When some grammatical purist insists, for example, that the subject has to go before the verb, aren’t we tempted to reply, “Sez you!”?

English is not so much a human invention as it is a force of nature, one that endures and flourishes despite our best attempts to ruin it. And believe it or not, the real principles of English grammar—the ones that promote clarity and sense—weren’t invented by despots but have emerged from the nature of the language itself. And they actually make sense!

So when you think about the rules of grammar, try to think like that guy in the back of the room, and never be afraid to challenge what seems silly or useless. Because what seems silly or useless probably isn’t a real rule at all. It’s probably a misconception that grammarians have tried for years to correct. There are dozens of ersatz “rules” of English grammar. Let’s start with Public Enemy Number 1. Myth #1: Don’t Split an Infinitive.

“Split” all you want, because this old superstition has never been legit. Writers of English have been doing it since the 1300s.

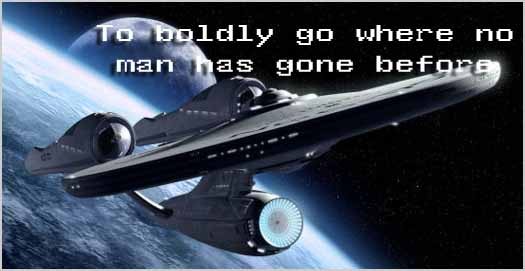

Where did the notion come from? We can blame Henry Alford, a 19th-century Latinist and Dean of Canterbury, for trying to criminalize the split infinitive. (Latin, by the way, is a recurring theme in the mythology of English grammar.) In 1864, Alford published a very popular grammar book, A Plea for the Queen’s English, in which he declared that to was part of the infinitive and that the parts were inseparable. (False on both counts.) He was probably influenced by the fact that the infinitive, the simplest form of a verb, is one word in Latin and thus can’t be split. So, for example, you shouldn’t put an adverb, like boldly, in the middle of the infinitive phrase to go—as in to boldly go. (Tell that to Gene Roddenberry!)

Grammarians began challenging Alford almost immediately. By the early 20th century, the most respected authorities on English (the linguist Otto Jespersen, the lexicographer Henry Fowler, the grammarian George O. Curme, and others) were vigorously debunking the split-infinitive myth, and explaining that “splitting” is not only acceptable but often preferable. Besides, you can’t really split an infinitive, since to is just a prepositional marker and not part of the infinitive itself. In fact, sometimes it’s not needed at all. In sentences like “She helped him to write,” or “Jack helped me to move,” the to could easily be dropped.

But against all reason, this notorious myth of English grammar lives on—in the public imagination if nowhere else.

This wasn’t the first time that the forces of Latinism had tried to graft Latin models of sentence structure onto English, a Germanic language. Read on.

MORE: Myth #2: Don’t End a Sentence With a Preposition.

Yeah, Right < /s>

At last, a constructive outlet for my hostilities and frustrations: I can split infinitives! Thx for the idea.

As someone with a side business of editing/proofreading, I will say one thing in defense of these rules. Many of them many not be formally “wrong,” and English writers often use them, and have for quite a long time. Nevertheless, adhering to these rules will help keep you from sounding like an uneducated dunderhead.

Rules I break because grammar is cheaper that speeding.

My Grammar was no myth, she was a mythuze.

But there are some rules up with which we need not put.

Like a violin, language in the hands of a master is both beautiful and enriching. Though he broke “the rules” from time to time, Winston Churchill is a joy to read.

Today’s TwitSpeak, by contrast, is like the scratching and scraping of a lazy and undisciplined violin student. It doesn’t matter if he IS trying to play a Bach sonata; I won’t waste my time trying to understand him.

YMMV

As a proponent of standard English, I was concerned about the subject matter. Since one of the main authorities in support of the author’s positions is the great Fowler, I relaxed. Unfortunately, dear Mrs. Skubby from 3rd grade is certainly dead by now, so I can’t rebuke her for telling her class not to begin sentences with conjunctions.

I like that! I didn’t think you were supposed to use a comma before “and” at the end of lists though? For example, I thought it was milk, bread and cheese; not milk, bread, and cheese.

How’d you like me slipping in that semicolon? :)

And as Fowler noted, adhering to those rules to produce a clumsy and inexact sentence reveals you as an educated dunderhead.

Actually I think adhering to those rules will more often than not make you sound like an uneducated dunderhead. That’s part of the point of the article, in most of the sample sentences she give trying to follow the bad rules creates unnatural sounding sentences with little flow.

And the use of the colon as a half-stop in a sentence is absolutely dramatic. And effective.

People really don’t have much tolerance for grammatical mistakes in print. Every now and again, OK. Were this not true, Microsoft wouldn’t have constructed the grammar/thesaurus/style check.

Besides, visual thesaurus is a fun site.

Nice parchment.

Today, almost any word beginning with a vowel is morphing to ‘uh’ in common usage. This is very prevalent in all new-casts and other public sources.

immediately = uhmediately

emotional = uhmotional

et al...

Of course, the old standbys are

specifically = pacifically

experiment = exspearmint

I only point these cases out because they span dialect. It is not a southern vs. northern vs. California, thing. It is becoming an accepted part of the English language nationwide. You can even hear irregardless in some news-casts and it even passes most spell checkers. lol

I am having trouble digesting that post; I’m sure it will all come out OK, though.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.