The capture of Aguinaldo was placed by the Americans as one of their priorities. He was able to avoid capture for quite sometime, though. That was due to the loyalty of many townspeople in the different provinces, who warned his party whenever American troops were closing in. He was also able to win some more time because of the heroic sacrifice of General Gregorio del Pilar, the “boy general” in the famous Battle of Tirad Pass on December 2, 1900, in Mountain Province. In this narrow 2,800-meter-high pass, General del Pilar, with a handpicked force of only 60 men, held off for more than five hours a battalion of Texans of the U.S. 33rd Volunteers led by Major Peyton C. March. They had been pursuing Aguinaldo and his party. Of the 60, 52 were killed and wounded; one of the last to be killed was General del Pilar.

Navy Campaign Streamer - Philippine Insurrection

Aguinaldo was finally captured on March 23, 1901, in Palanan, Isabela Province, by means of a trick planned by Brigadier General Frederick Funston. A party of pro-American Macabebe scouts marched into Palanan pretending to be the reinforcements that Aguinaldo was waiting for. With the Macabebes were two former Filipino army officers, Tal Placido and Lazaro Segovia, who had surrendered to the Americans, and five Americans, including General Funston, who pretended to be captives. Caught by surprise, Aguinaldo’s guards were easily overpowered by the Macabebes after a brief exchange of shots. Aguinaldo was seized by Tal Placido and placed under arrest by General Funston. He was brought to Manila to be kept a prisoner at Malacañang. There he was treated by General MacArthur more as a guest than as a prisoner. On April 1, 1901, convinced of the futility of continuing the war, the ambivalent Aguinaldo swore allegiance to the United States.

On April 19,1901, Aguinaldo issued a proclamation calling on the Filipino people to lay down their arms and accept American rule. His capture signalled the death of the First Philippine Republic. But the war continued. Dragged by Galloping Horses. During the war, torture was resorted to by American troops to obtain information and confessions. The water cure was given to those merely suspected of being rebels. Some were hanged by the thumbs, others were dragged by galloping horses, or fires lit beneath others while they were hanging. Another form of torture was tying to a tree and then shooting the suspect through the legs. If a confession was not obtained, he was again shot, the day after. This went on until he confessed or eventually died.

Villages were burned, townfolks massacred and their possessions looted. In Samar and Batangas, Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith and General Franklin Bell, respectively, ordered the mass murders in answer to the mass resistance.

On the other hand, Filipino guerrillas chopped off the noses and ears of captured Americans in violation of Aguinaldo’s orders. There were reports that some Americans were buried alive by angry Filipino guerrillas. In other words, brutalities were perpetrated by both sides.

The so-called Balangiga Massacre happened in 1901, a few weeks after a company of American soldiers arrived in Balangiga, Samar, upon the request of the town mayor to protect the inhabitants from the raids of Muslims and rebels. How the massacre took place is best described in Joseph Schott’s book, The Ordeal of Samar (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc./Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc., Publishers, Indianapolis, Indiana, Copyright 1964). Here’s an excerpt from the book:

On the night of September 27, the sentries on the guard posts about the plaza were surprised by the unusual number of women hurrying to church. They were all heavily clothed, which was unusual, and many carried small coffins. Sergeant Scharer, sergeant of the guard vaguely suspicious, stopped one woman and pried open her coffin with his bayonet. Inside he found the body of a dead child.

“El calenturon! El colera!” the woman said.

The sergeant, slightly abashed by the sight of the dead child, nailed down the coffin lid again with the butt of his revolver and let the woman pass on. He concluded that cholera and fever were in epidemic stage and carrying off children in great numbers. But it was strange that no news of any such epidemic had reached the garrison.

If the guard sergeant had been less abashed and had searched beneath the child’s body, he would have found the keen blades of cane-cutting knives. All the coffins were loaded with them.

The night passed and morning came. At about 6:20 a.m. a sergeant was in the door of his squad hut. At that time, the unarmed Americans were going to breakfast. Some of them, of course, had finished their breakfast.

The sergeant saw Pedro Sanchez, chief of police of the town, line up prisoners for work. Then Sanchez sent all the workers to work in the plaza and in the streets. After that, Sanchez went to a hut and even talked with a corporal who knew pidgin Spanish and Visayan. After speaking with the corporal, Sanchez walked behind Private Adolph Gamlin, the sentry on the area. All of a sudden, Sanchez grabbed the Gamlin’s rifle, and he smashed the rifle’s butt on the American soldier’s head. The Filipino fired a shot and shouted a signal. Then pandemonium broke loose.

Joseph L. Schott, describes what happened next:

The church bell ding-donged crazily and conch shell whistles blew shrilly from the edge of the jungle. The doors of the church burst open and out streamed the mob of bolomen who had been waiting inside. The native laborers working about the plaza suddenly turned on the soldiers and began chopping at them with bolos, picks and shovels.

As the church bells were being rung, Sanchez fired upon the Americans at the breakfast table. He then led the Filipinos in attacking the American soldiers.

Schott continues:

The mess tents, filled with unarmed soldiers peacefully at breakfast, had been one of the first prime targets for the attackers. They burst in screaming and slashing....

Then, as the soldiers rose up and began fighting with chairs and kitchen utensils, the attackers outside cut the tent ropes, causing the tents to collapse on the struggling men. The natives ran in from all directions to slash with bolos and axes at the forms struggling under the canvas.

Members of C Company were almost all massacred during the first few minutes of attack. The main action took place around the plaza and tribunal building. There, Filipino bolomen attacked the soldiers. They boloed to death the Americans who tried to escape; other soldiers were hacked from nose to throat.

About 250 Filipinos were reported to have been killed by a number of American troops who were able to get rifles from the rack and shoot at the bolomen. (However, first-hand Filipino accounts put the dead at less than 40.) On the other hand, the Americans suffered 78 casualties: 48 killed and 22 wounded. Only 4 were not injured. (Gamlin survived the massacre. He died at age 92 in the U.S. in 1969.)

Due to the public demand in the U.S. for retaliation, President Theodore Roosevelt ordered the pacification of Samar. And in six months, General “Jake” Smith transformed Balangiga into a “howling wilderness.” He ordered his men to kill anybody capable of carrying arms, including ten-year old boys. Smith particularly ordered Major Littleton Waller to punish the people of Samar for the deaths of the American troops. His exact orders were:

“I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn, the better you will please me.”

Maybe these shouts were heard while the Americans were chasing and shooting the guerrillas and their sympathizers. And maybe, too, some U.S. troops might have uttered: “So there you are! You’ve no where to go!” And the shots were heard as burning houses lighted the night.

When the campaign was over, the U. S. army court-martialed and retired General Smith from the service. There were reports that about one third of the entire population of Samar was annihilated during the campaign. Moreover, when members of the U.S. Army 11th Infantry Regiment left Balangiga, Samar, they took with them two church bells from the Balangiga Catholic Church. They were placed in a brick display museum in their home base Fort Russell, Wyoming, where they still remain today.

General Miguel Malvar of Batangas, who took over the leadership of the fallen Aguinaldo, continued the fight. He was the commanding general of all forces south of the Pasig River. The Americans committed barbaric acts because of the population’s support to the guerrillas.

For instance, by December 25, 1901, all men, women, and children of the towns of Batangas and Laguna, were herded into small areas within the poblacion of their respective towns. The American troops burned their houses, carts, poultry, animals, etc. The people were prisoners for months.

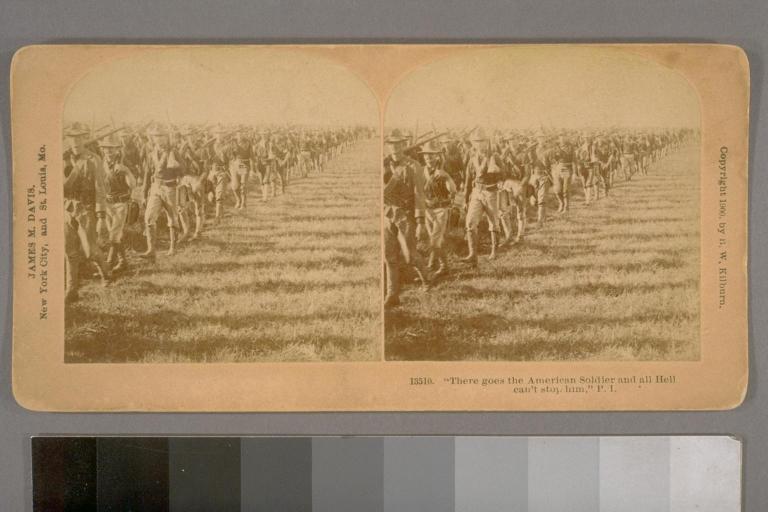

"There goes the American Soldier and all Hell can't stop him." P. I..

Those acts were considered by many as an early version of the concentration camps used by American soldiers in the Vietnam War. The same tactics were perpetrated by the American army against non-combatants from March to October 1903 in the province of Albay and in 1905 in the provinces of Cavite and Batangas.

Many Filipino soldiers and military officers surrendered to the Americans, but there were some who refused to give up. On February 27, 1902, General Vicente Lukban, who resorted to ambushing American troops in Samar, was captured in Samar. General Malvar surrendered to General J. Franklin Bell in Lipa, Batangas, on April 16, 1902.

On July 4, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt declared that the Philippine-American War, which Americans called the Philippine Insurrection, was over. He made the declaration after the Philippine Commission reported to Roosevelt that the recent “insurrection” in the Philippines was over and a general and complete state of peace existed.

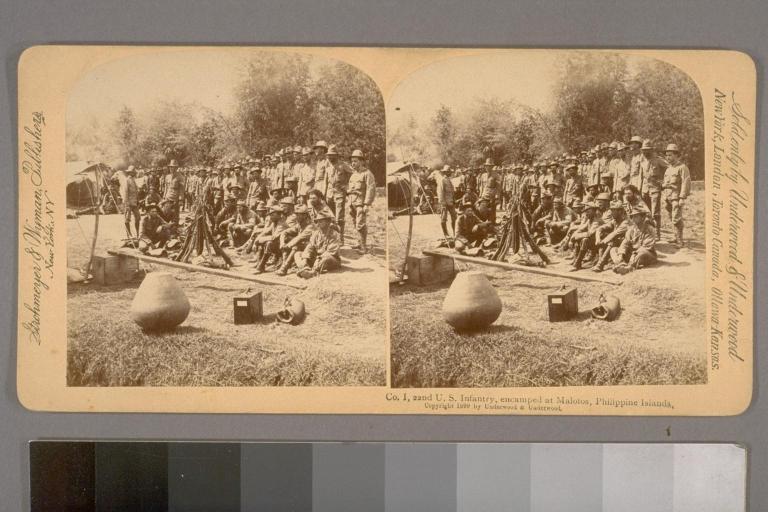

Co. I, 22nd U. S. Infantry, encamped at Malolos, Philippine Islands.

Official history proclaims Filipino struggle against the Americans as a short one and honors those who connived with the Americans. But little importance has been given to those who stood by the original goals of the Katipunan.

However, according to author Constantino, peace in the Philippines was merely propaganda. He said, in reality, the reports of the American commanding general and several governors showed that numerous towns and villages remained in a state of constant rebellion. They themselves recognized that this could not have continued without the people’s support. Many collaborators were killed by resistance forces. The civil government, composed of 6,000 men, was established. It was, however, led by American officers and former members of the Spanish civil guards.

Initially, the highest rank a Filipino could hold was only second lieutenant. (Americans continued to head the constabulary until 1917.) The constabulary was used to quell local resistance. Constantino terms these suppressive efforts of using a native force “the original Vietnamization.” He adds that some military techniques employed against Philippine resistance groups “strikingly similar to those that have more recently shocked the world.”

The necessary Result of War -- an Insurgent killed in the trenches at the Battle of Malabon, P. I..

Many resistance groups under different leaders had emerged during the war years. Luciano San Miguel, who joined the Katipunan in 1886 revived the Katipunan in his command in Zambales Province. He was a colonel when the Philippine-American War broke out. As a commander, he participated in the battles of 1899 in central and western Luzon, including Morong and Bulacan.

In 1902, he was elected national head of the revived Katipunan. He continued the guerrilla war. He died in a battle with Philippine Constabulary and Philippine Scouts in the district of Pugad-Baboy, in Morong, now Metro Manila.

Faustino Guillermo, assumed the leadership of the new Katipunan movement when San Miguel was killed. Others who took part in the guerrilla warfare were Macario Sakay, who had been with Bonifacio and Jacinto during the initial struggles of the Katipunan, and Julian Montalan and Cornelio Felizardo.

A Sixth Artillery Gatling Gun, driving Insurgents out of the brush, Pasay, P. I..

The Philippine Constabulary, Philippine Scouts, and elements of the United States Army combined to go after the guerrillas. In the province of Albay, General Simeon Ola launched guerrilla raids on U.S.-occupied towns until his surrender on September 25, 1903. He was the last Filipino general to surrender to the Americans. Sakay, leader of a band of patriotic Filipinos and whom the Americans branded as a bandit, continued to fight. He even established the Tagalog “Republic.”

He surrendered on July 14, 1906. Sakay and his men were tried and convicted as bandits. Sakay was hanged on September 13, 1907.