Posted on 03/07/2012 4:30:52 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

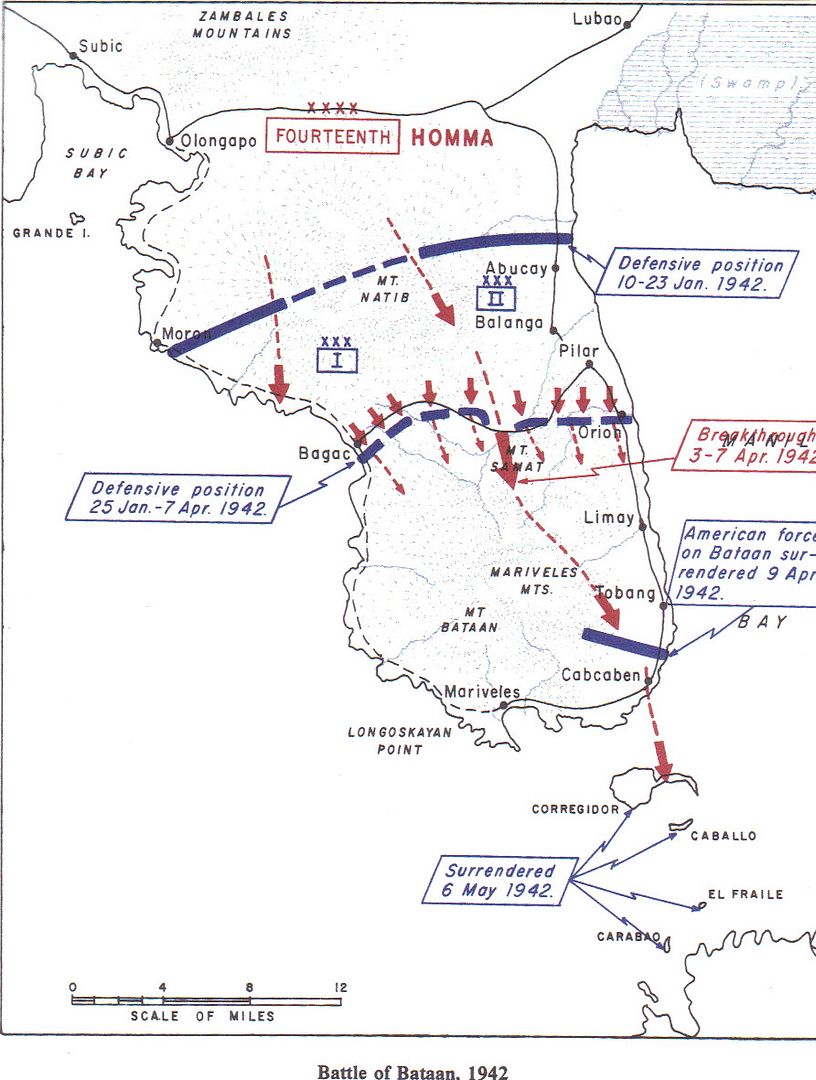

The West Point Military History Series, Thomas E. Griess, Editor, The Second World War: Asia and the Pacific

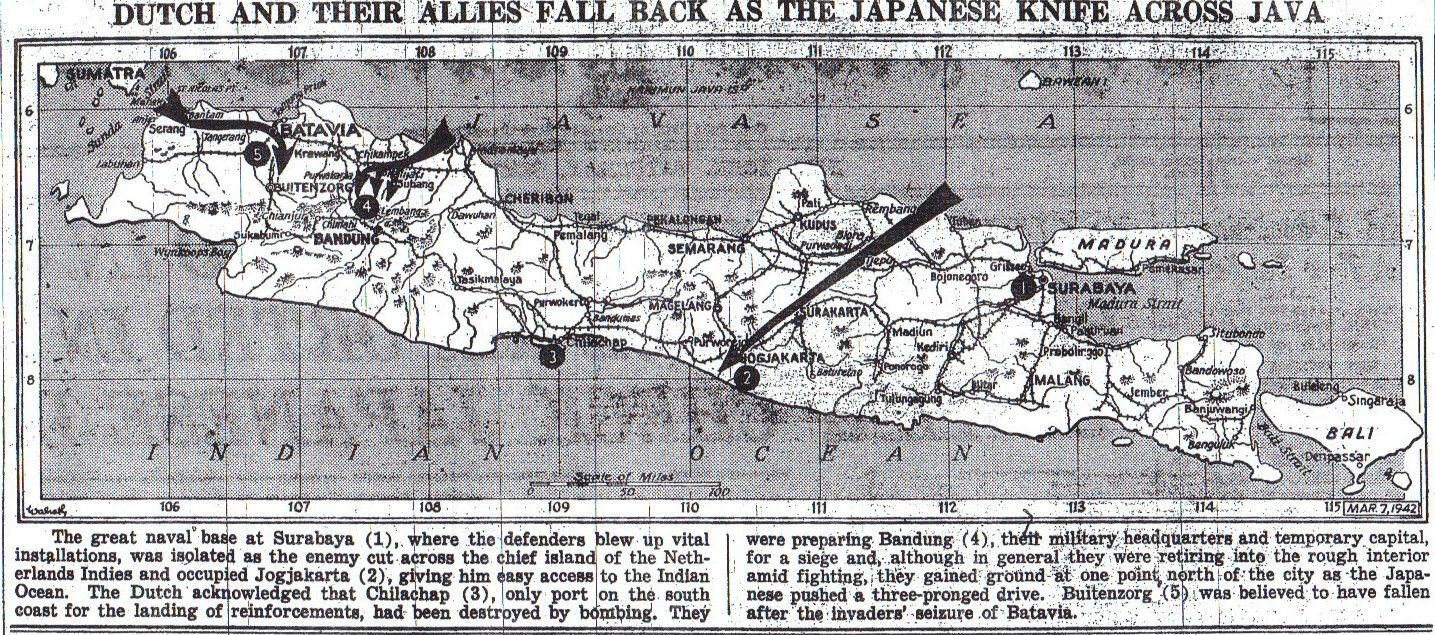

Defenders Retire – 2

U.S. Bombers Leave Java, Balked by Lack of Fighters (by Harold Guard, first time contributor – 3)

U.S. Aid is On Way – 3-4

Attack Near Pegu – 4-5

The War Summarized – 5

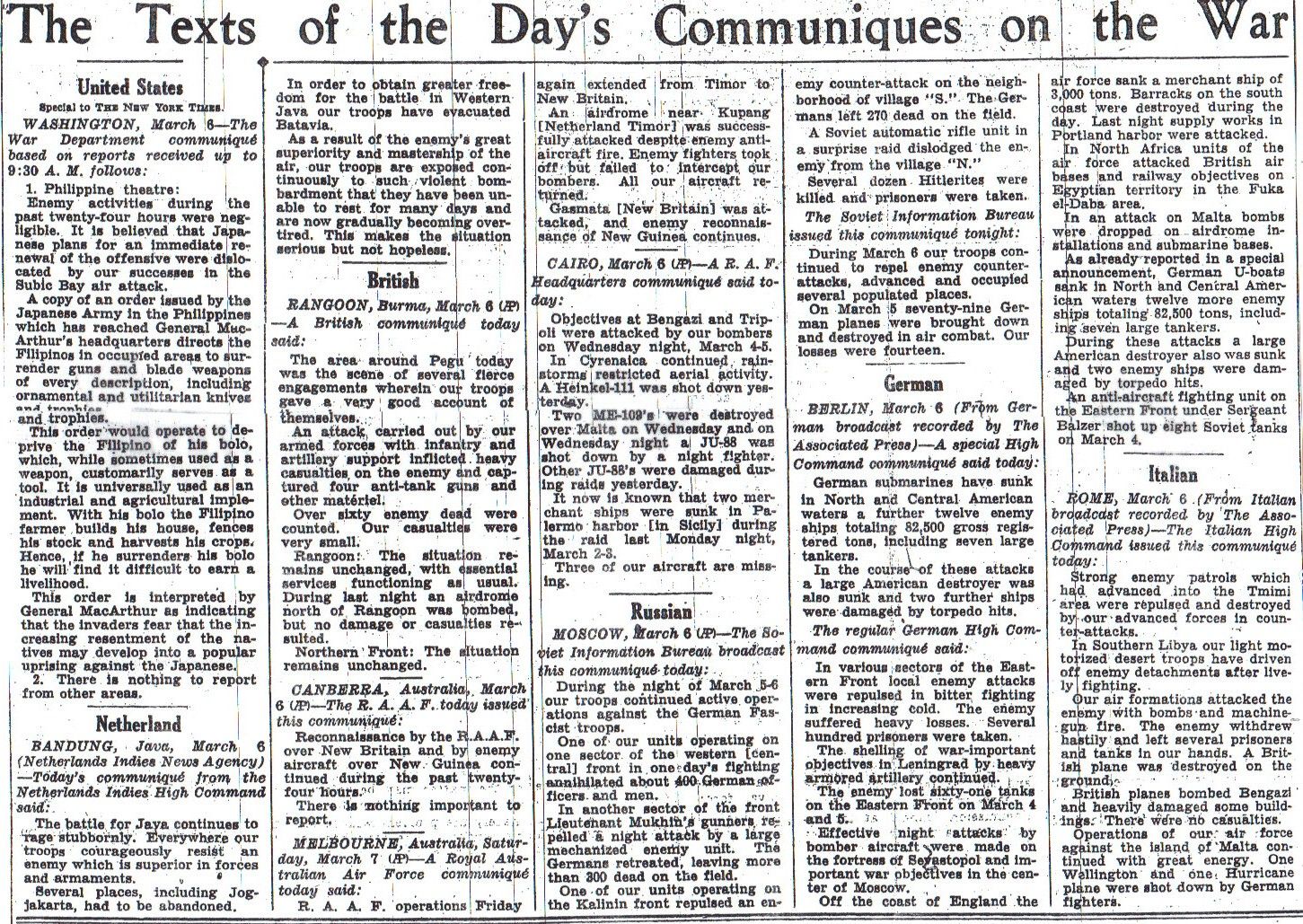

The Texts of the Day’s Communiques on the War – 7-8

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1942/mar42/f07mar42.htm

British abandon Rangoon

Saturday, March 7, 1942 www.onwar.com

British destroy supplies before retreatingIn Burma... The British troops leave Rangoon and Pegu, retiring north. The fall of port at Rangoon means that all Allied supplies must be brought in overland from India. By nightfall, the Japanese 33rd Division occupies the city.

In the Dutch East Indies... Japanese forces takes Surabaya and Lembang on Java

In New Guinea... The Japanese invasion forces land in the Salamaua area.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/frame.htm

March 7th, 1942

UNITED KINGDOM:

Escort carrier HMS Tracker launched.

Destroyer HMS Zetland launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

FRANCE: During the night of the 7th/8th, RAF Bomber Command flies two missions: (1) 15 aircraft bomb the submarine pens at St Nazaire and (2) 11 Hampdens lay mines off Lorient; one Hampden is lost. (Jack McKillop)

GERMANY: Berlin: Hundreds of thousands of Germans and people from Nazi-occupied Europe face being forced to work on German farms. A plan announced today looks first to people from country districts and provincial towns to provide extra labour; as many as 800,000 people could be needed at harvest time. Refusal to undertake such work could lead to what are described as draconian punishments. But attempts to draft women over 55 or those who are pregnant have already encountered strong opposition. Attention is therefore expected to focus on women from more affluent circles as these are thought by Nazi officials to contain the most “shirkers.”

U-211, 179 commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

MALTA: Fifteen Mk VB Spitfires, the first to serve outside the United Kingdom, are delivered to Malta by the aircraft carrier HMS EAGLE. (22)

GIBRALTAR: Force H, consisting of the aircraft carriers HMS Argus and Eagle and supported by a number of destroyers, sets sail for Malta with a number of Spitfires on board. Fifteen Spitfires were flown off when Force H comes within range of the island. (Jack McKillop)

BURMA: The British Army evacuates Rangoon, moving along Prome road except for demolition forces, which are removed by sea. The loss of Rangoon seriously handicaps supply and reinforcement of the Burma Army, which must now depend on air for this. Withdrawal from Rangoon is halted at Taukkyan by an enemy roadblock. The bypassed Allied force in Pegu is ordered to withdraw. (Jack McKillop)

NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES: Java: Japanese troops occupy Lembang.

Bandoeng: The fight to save Java is over. Displaying white flags, a convoy of cars led by the Dutch C-in-C, Lieutenant-General ter Poorten, is driving this evening to the Japanese occupied airport at Kalidjati, 25 miles to the north, to open negotiations for surrender. Hours earlier the 15 most senior members of the Dutch government and armed forces led by Dr van Mook, the lieutenant-governor of the East Indies, escaped by air to Australia from the last Allied-held airstrip.

At noon the Netherlands News Agency in Bandoeng, the Dutch HQ, transmitted its last bulletin to the outside world, ending with: “Now we shut down. Long live our queen! Goodbye till better times.”

Reporting on the last 24 hours it said that the situation in the west part of the island had become critical since the decision to surrender Jakarta by turning it into an open city two days ago. Dutch forces were now outnumbered five to one and the Japanese had absolute air supremacy. Rail links between east and west Java had been severed, and Dutch troops were now blowing up installations to stop them falling into the hands of the enemy.

The Japanese conquest of Java is virtually complete. Radio and cable communications with Bandoeng cease. Final reports indicate that the Japanese are still advancing on all fronts, that the defenders are completely exhausted, and that all Allied fighter planes have been destroyed. The Japanese also capture Tjilatjap, the naval base on the south coast, and Surabaja was being evacuated in the face of strong Japanese forces. (Jack McKillop)

NEW GUINEA: Japanese landings at Salamaua by the South Seas Detachment.

While returning from a reconnaissance mission over Gasmata and Rabaul in the Bismarck Archipelago, the crew of an RAAF Hudson of No. 32 Squadron, based at Seven Mile Airstrip, Port Moresby, sights a convoy of 11 ships heading for Salamaua. (Jack McKillop)

NEW CALEDONIA: Major General Alexander M. Patch, commander-designate of the New Caledonia Task Force, arrives on New Caledonia Island. (Jack McKillop)

AUSTRALIA: USN Patrol Wing Ten (PatWing-10), which was based in the Philippines in December 1941, completes withdrawal from the Netherlands East Indies, and establishes headquarters in Perth, Western Australia, for patrol operations along the west coast of Australia. Sixty percent of the wing personnel are either dead or captives of the Japanese. Three of the four wing squadrons, Patrol Squadron Twenty One (VP-21), VP-22 and VP-102 are officially disestablished, and the remaining personnel and aircraft assets, PBY-4 and -5 Catalinas, are combined to bring up to full strength the remaining squadron, VP-101. (Jack McKillop)

Minesweeper HMAS Dubbo launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

CANADA: Trawler HMS Magdalen launched Midland, Ontario.

HMC ML 068 commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

U.S.A.: The Tuskegee flying school graduates its first cadets. This US school was segregated for Black students. They joined the 99th Pursuit Squadron. Names: Capt. Ben Davis Jr.; 2LT Mac Ross, Charles DeBow, LR Curtis, and George Roberts. (Michael Ballard)

The practicability of using a radio sonobuoy in aerial anti-submarine warfare was demonstrated in an exercise conducted off New London, Connecticut, by nonrigid airship (or blimp) K-5 and submarine USS S-20 (SS-125). The buoy could detect the sound of the submerged submarine’s propellers at distances up to 3 miles (5 kilometres), and radio reception aboard the blimp was satisfactory up to 5 miles (8 kilometres). (Jack McKillop)

Light cruiser USS Vincennes laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN:

Hog Islander Cardonia sunk by U-126 about 9 miles (14 kilometres) north-northwest of West Tortuga Island, Haiti at 19.53N, 73.27W.

U-126 later sinks an unarmed U.S. freighter about 5 miles (8 kilometres) west-northwest of San Nicholas Mole, Haiti.

Unarmed Brazilian steamship SS Arabutan sunk by U-155 about 110 miles east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, at 35.15N, 73.55W.

Steam tanker Unilawenco sunk by U-161 at 13.23N, 62.04W.

At 2314, steam trawler Nyggjaberg was hit by one torpedo from U-701 and sank within two minutes south of Iceland.

At 0835, the unescorted and unarmed Barbara was hit by a torpedo amidships on the port side, despite sailing an approved zigzagging course in moonlight. The torpedo penetrated the hull deep and exploded on the starboard side, causing a fire which damaged the engines, killed the watch below and reached mast high amidships. The fire prevented the survivors from launching any lifeboats, so they had to jump or climb into the water and swim to the life rafts. The ship burned for two and a half hours and sank stern first about nine miles north-northeast of Tortuga Island, Dominican Republic. On 9 March, the master, 15 men and a stewardess were picked up after three days at sea by a USN PBY Catalina flying boat several miles off Porta l’Ecu, Haiti. The pilot who risked two landings and overloaded his plane was cited for the act. A group of 21 survivors landed on Tortuga Island after nearly three days at sea. Able Seaman Maximo Murphy walked 18 hours across the island to get help from natives, who send a Haitian Coast Guard vessel to the survivors. Murphy earned the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal for his actions. Two other rafts with 19 survivors made it to the shore safely. Bosun Charles Rooney and AB John Taurin had released a portable gangway when the ship was sunk and clung to this gangway along with a passenger, who died on the second day. Both men were spotted by an aircraft on the forth day and were picked up by a destroyer, which was directed to them by the aircraft. Of the eight officers, 50 crewmen and 27 passengers aboard, four officers, 14 crewmen and eight passengers lost their lives. The master Walter Gwynn Hudgins later commanded the Elizabeth, which was sunk by U-103 on 21 May 1942. (Jack McKillop and Dave Shirlaw)

Last time I checked, GRAF ZEPPELIN was an aircraft carrier, and was never completed. As for 35,000 ton, 15” battleships, the Germans , under Plan ‘Z’, only ever intended to build two, BISMARCK and TIRPITZ. They DID plan to buld six more battleships. Only MUCH bigger.

"Organized into a column and with their meager belongings in sacks, Jews march into Belzec.

The prisoners were deceived by their guards, who told them they had entered a transit camp from which they would be assigned to various labor camps. Instead, they were sent to the gas chambers."

COLONEL-GENERAL Halder's car swung out of the Mauer Forest in East Prussia, where OKH, the High Command of Land Forces, was situated in a well-camouflaged spot, on to the road to Rastenburg. A spring gale was sweeping through the branches of the ancient beech forest. It was whipping up the surface of the Mauer Lake into white caps, and it was driving the clouds so low over the ground that one almost expected to see them slit open by the tall stone cross on the hill where the military cemetery of Lötzen was situated.

It was the afternoon of 28th March 1942. Colonel-General Halder, Chief of the Army General Staff, was driving over to Hitler's Headquarters at the "Wolfsschanze," hidden in the forests of Rastenburg.

On the lap of his orderly officer lay a briefcase—at that moment perhaps the most valuable brief-case in the world. It contained the German General Staff's operational plan for 1942. In his mind Halder once more rehearsed his proposals.

The ideas, thoughts, and wishes voiced by Hitler as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces at the daily situation conferences had been laboriously written up by Halder into a carefully considered draft. The main feature of the plan of campaign for 1942 was a full-scale attack in the southern sector towards the Caucasus; its objective was the destruction of the bulk of the Russian forces between Donets and Don, the gaining of the passes across the Caucasus, and eventually the seizure of the vast oilfields along the Caspian Sea.

The Chief of the General Staff was not happy about the plan.

He was beset by doubts whether a major German offensive was justified after the heavy drain of strength during the winter. Many a dangerous crisis which the reader of the preceding posts will already have seen liquidated was then, at the end of March, still causing anxiety to the German High Command and the General Staff of the Army. At that time too, General Vlasov's Army on the Volkhov had not yet been finally defeated. Count Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt with the divisions of his II Corps was still surrounded in the Demyansk pocket. "Operation Bridge-building" had begun, but had not yet been successfully accomplished. In Kholm, Scherer's combat group had yet to be relieved.

Even in the Dorogobuzh-Yelnya area, only 25 miles east of Smolensk, the situation was still critical at the end of March. There the Soviets were operating with units of their Thirty-third Army, the 1 Guards Cavalry, and the IV Airborne Corps. Farther north the Soviet Thirty-ninth Army and the XI Cavalry Corps were still holding the dangerous front-line prominence west of Sychevka.

But these were by no means all the worries in the mind of the Chief of the General Staff at the end of March.

In the Crimea Manstein with his Eleventh Army was still immobilized before Sevastopol, and the Kerch Peninsula had even been recaptured by the Russians in January. But the situation was most critical of all near Kharkov, where heavy fighting had been going on since mid-January.

The Soviet High Command was making a supreme effort to nip Kharkov off in a pincer movement. The northern jaw of the pincers had been held at Belgorod and Volchansk, but the southern jaw, the Soviet Fifty Seventh Army, had breached the German Donets front on both sides of Izyum over a width of 50 miles. The Soviet divisions had already established a bridgehead 60 miles deep. The spearheads of the attack were threatening Dnepropetrovsk, the supply centre of Army Group South. Whether this Soviet penetration in the Izyum area would develop into a dam-burst of incalculable consequences depended on whether the two cornerstones north and south of the penetration point, Balakleya and Slavyansk, could be held.

For the past few weeks these points had been held by the battalions of two battle-weary German infantry divisions in what had already become a heroic saga of defensive fighting. On its outcome depended the entire future of the southern front. Slavyansk was held by the 257th Infantry Division from Berlin, and Balakleya by the 44th Infantry Division from Vienna.

In savage and destructive engagements the Berlin regiments under General Sachs, and later under Colonel Rüchler, defended the southern edge of the Izyum bend. A combat group under Colonel Drabbe, commanding 457th Infantry Regiment, displayed such skill, valor, and self-sacrifice in fighting for the miserable villages, collective farms, and small homesteads that even the Soviet operation reports—as a rule very reticent about German feats of arms—were full of admiration.

The village of Cherkasskaya was typical of this kind of fighting. In eleven days Drabbe's group lost there nearly half of its 1000 men. Some 600 defenders were manning an all-round front of 8-1/2 miles. Soviet dead actually counted in front of this village numbered 2,100. Eventually the Russians took the village, but it had by then consumed the strength of five full Soviet regiments.

Before leaving his headquarters for the "Wolfsschanze" in the afternoon of 28th March, Colonel-General Halder had asked for the operations report of 257th Infantry Division about the battle that had now been raging for seventy days. He wanted the division to be cited in the High Command communiqué: to date its regiments had repulsed 180 separate enemy attacks, and 12,500 Soviet dead had been counted in front of its lines. Three Soviet rifle divisions and a cavalry division had been mauled, and four more rifle divisions and an armored brigade had taken a heavy toll. The German casualties, admittedly, also testified to the brutality of the fighting: they amounted to 652 killed, 1663 wounded, 1689 frostbitten, and 296 missing—a total of 4300 men, half the total losses suffered by the division in ten months' fighting in Russia.

That was the horror and butchery of Slavyansk.

The northern edge of the Izyum penetration, the Balakleya area, was held by the Viennese 44th Infantry Division, whose 134th Infantry Regiment was the successor of the ancient Hoch-und-Deutschmeister Regiment. The division under Colonel Debois held a front from Andreyevka through Balakleya and Yakovenkovo to Volokhov Yar. That was a line of 60 miles. And along those 60 miles an entire Soviet Corps was attacking, reinforced by armor and rocket batteries.

Here, too, the combat groups and their commanders were the inspiration of the resistance. The exploits of the combat group under Colonel Boje, commanding 134th Infantry Regiment, in the vital sectors of Yakovenkovo and Volokhov Yar, on the high bank of the Balakleya, whipped by icy winds, are among the most incredible chapters of this horrifying war in the East.

The fighting hinged on villages and farms—in other words, on the troops' shelter quarters. In a temperature of 50 degrees below zero a house and a hot stove, offering as they did the chance of an hour's sleep, became a matter of life and death. The Germans clung to the villages, and the Russians tried to drive them out of them, because they too wanted to get away from their snowy fortifications, behind which they assembled for attack, to find a roof, a warm corner, and a few hours' sleep without the fear of freezing to death.

Once more the war centered around the most elementary requirements of life. Germans and Russians alike spent their last ounce of strength. For once the interests of the men in the line and those of the General Staffs coincided: both wanted Balakleya and the villages to the north which were being held by 44th Infantry Division—the former for the sake of the houses and the latter for reasons of strategy. If the cornerpost of Balakleya and the high ground commanding the road to the west were to be lost Timoshenko would be able to convert his penetration at Izyum into a large-scale strategic breakthrough into Kharkov.

But Balakleya held on, stubbornly defended by the 131st Infantry Regiment under Colonel Poppinga. But, north of it, Strongpoint 5 of 1st Battalion, 134th Infantry Regiment, was attacked by such massive numbers that it could not be held. The battalion resisted the Soviet tank attacks until every last man in the battalion was killed, including all its wounded who were put to death by the Soviets.

Among those killed in action was First Lieutenant von Hammerstein, a nephew of the former Chief of the Army Directorate, von Hammerstein-Equord. Young officers like Hammerstein, ready for any kind of action or sacrifice, were typical of these dreadful defensive battles. Together with the hard-boiled fearless old sergeants and corporals, they formed small fighting parties which almost invariably pulled off incredible exploits.

Thus First Lieutenant Vormann with remnants of 2nd Company smashed an entire Soviet battalion in a savage night engagement. First Lieutenant Jordan, commanding 13th Company, personally lay in front of the Russian lines at Yakovenkovo night after night, directing the fire of his Infantry guns against enemy machine-gun positions on the hill, and one after the other putting them out of action.

Vormann and Jordan are both buried at Stalingrad.

The ferocity of the fighting in the Balakleya sector is also shown by the fact that Colonel Boje himself and his staff were forced more than once to join in hand-to-hand fighting with pistol and hand-grenade. A Soviet ski battalion eventually reached the crucial Balakleya-Yakovenkovo road on the southern flank of the combat group and established itself in huge ricks of straw. Boje threw in his last reserves to save his combat group from the mortal danger of encirclement. The Russians did not yield an inch. Even when their straw ricks had been set ablaze by Stukas they still fired their guns and defended themselves to the end.

The interesting thing about that terrible fighting was that the decisive role was invariably played by the individual.

Altogether, the successful defensive battles fought by the German troops in the winter and spring of 1942 hinged very largely upon the individual soldier. He was—certainly still at that time—superior to his Russian opposite number in experience and fighting morale. This fact alone explains the astonishing feats performed by German troops, frequently depending entirely on themselves, all along the front from Schlüsselburg down to Sevastopol against a numerically and materially superior enemy.

The following instance of courage, sangfroid, and practical skill from the hotly contested Kharkov area is typical of many. In March 1942 the 3rd Panzer Division was employed in that sector in the role of a fire-brigade on a continually threatened front. In the Nepokrytaya sector Sergeant Erwin Dreger with fifteen men of 1st Company, 3rd Rifle Regiment, was holding a front of a little over a mile. That, of course, was possible only because of the particular tactics thought up by Dreger and thanks to his men's nerves of steel—all of them Eastern Front veterans. From stocks of captured material Dreger had armed every one of them with a machine-gun, keeping three more guns in reserve, just in case. Inside the village, and along the edge of it as well as all over the ground outside, piles of captured machine-gun ammunition had been laid out so that the guns could be operated without a No. 2 to look after the ammunition-belts.

Dreger's men were spaced out in a wide arc, facing the corner of a patch of woodland from where the Russians regularly mounted their attacks. It was at that point—though, of course, neither Dreger nor 3rd Panzer Division realized it —that the Soviet forward detachments intended to launch their break-through. The date chosen by them was 17th March. Towards 1030 hours the Russians charged in battalion strength. Dreger with his machine-gun was in the middle —i.e., at the most rearward point—of the arc. The Russians were getting closer and closer without a single round being fired. Dreger had given his men strict orders: "Wait for me to open fire."

The spearheads of the enemy attack were within 50 yards when Dreger's "lead machine-gun" at last opened up. Although they were a hard-boiled lot, Dreger's men felt greatly relieved when at last they were permitted to fire. Since the enemy assault had aimed almost exactly at the centre of their defensive line it was possible to deal with it almost as if by envelopment. Under the effective fire from both flanks the Russian assault collapsed within twenty minutes. Whereas the Russians suffered very heavy casualties, Dreger's group had not lost a single man.

After an hour's pause the Russians directed pin-point artillery-fire at the machine-gun positions they had identified. But Dreger and his men merely laughed: needless to say, they had long abandoned their former positions and established themselves in new ones. The Russians made five attacks within fourteen hours. Five times their battalion collapsed in the concentrated machine-gun fire of Dreger's group. Sixteen determined men were opposing an enemy who was about a hundred times superior to them in numbers. Three days later, however, the war exacted the supreme price from Dreger too.

He and his platoon had in the end been forced out of the village. But in a temperature of 30 degrees below the men needed a house, a room, or a cellar for a few hours during the night, to protect them from the icy wind. Dreger intended to recapture a collective farm by a surprise coup. He was caught by a burst from a machine pistol. His men dragged him behind a straw rick and made him comfortable. Dreger was tapping his icy fingers against each other as if to warm them. And while doing so he seemed to be listening into the darkness of the icy Russian night. Softly the normally so undemonstrative man said to his comrades, "Listen -that's death knocking at the door."

With that he died.

Colonel-General Halder did not know the story of Sergeant Dreger—but he was well acquainted on that 28th March with the operational reports sent in by 44th Infantry Division about the fighting at Balakleya. On 13th February he had passed them on to Jodl for inclusion in the High Command communiqué. On the 14th the Viennese were cited for the first time. Six weeks had passed since then. The force of the Soviet assault had on the whole been broken by the astonishing resilience of the troops at the cornerposts of the Izyum bend. But even with optimism and confidence that this crisis, like all the rest, would soon be liquidated, there still remained the justified question: would it not be better to make a pause along the entire Eastern Front, including Army Group South, and to let the Russians attack and wear themselves out against the German defenses until their reserves were gradually spent?

That was the question which Halder had been asking himself and his officers time and again while planning the 1942 campaign.

But Major-General Heusinger, the Chief of the Operations Department, had objected that this course of action would mean losing the initiative, and hence an unpredictable amount of time. And time was on the Soviet side. If they were to be forced to their knees at all, then the attempt would have to be made soon.

Halder had accepted this point. But in his opinion any renewed offensive should have been aimed at the heart of the Soviet Union—against Moscow.

But that was precisely what Hitler was stubbornly opposing. He seemed to have a positive horror of Moscow.

Instead he had decided to try something entirely new after the unfortunate experiences on the Central Front in the previous year, and to seek the decision in the south by depriving Stalin of his Caucasian oil and by thrusting into Persia. Rommel's Africa Army played a part in this plan. The "desert fox," who was just then preparing his offensive from Cyrenaica against the British positions at Gazala and against Tobruk, the heart of the British defense of North Africa, was to advance right across Egypt and the Arabian Desert to the Persian Gulf. In this way Persia, the only point of contact between Britain and Russia, and after Murmansk the greatest supply base of US help for Russia, would be eliminated. Moreover, in addition to the Russian oilfields the very much richer Arabian oilfields would fall into German hands.

Mars had been appointed the God of economic warfare.

Halder's car stopped at the barrier at Gate 1 to Special Area I of the "Wolfsschanze," Hitler's Headquarters proper. The guard saluted. The barrier was raised. Along the narrow asphalted road the car drove on into Hitler's forest stronghold. The low concrete huts, with their camouflage paint and bush-planted flat roofs, lay perfectly hidden among the tall beeches. Even from the air they were impossible to make out. The whole area, over a wide radius, was hermetically sealed—protected by barbed-wire obstacles and belts of minefields. There were road-blocks on all roads. The small branch railway had been taken out of service and was now being used only by Goering's diesel coach plying to the Air Marshal's battle headquarters in the Johannisberg Forest near Lake Spirding, south of Rastenburg.

Colonel-General Jodl once remarked that the "Wolfsschanze" was a cross between a concentration camp and a monastery. It certainly was a Spartan military camp, differing from ordinary military establishments only in that Hitler turned night into day, working until two, three, or even four o'clock in the morning, and then sleeping until all hours. Whether they liked it or not, his closest collaborators also had to adapt themselves to this rhythm.

Halder drove past the information office of the Reich Press Chief.

On the right were the radio and telephone exchange of the camp, and next to it Jodl's and Keitel's quarters. On the left of the road were the quarters of Bormann and the Reich Security Service. On the farthest edge of the forest was Hitler's hut, surrounded by one more high wire fence. Together with his Alsatian bitch Blondi, this wire fence was the last obstacle outside Hitler's Spartan hermitage in the Rastenburg forest.

For that conference on 28th March Hitler had invited only a small circle, only the most senior leaders of the armed forces—Keitel, Jodl, and Halder, and half a dozen other top-ranking officers of the three services. They were standing or sitting on wooden stools around the oak map-table. Hitler sat in the middle of one of its long sides; the Chief of the General Staff occupied one of its narrow sides. Halder was given leave to speak and began to develop his plan.

Its code name was "Case Blue."

Originally it was to have been called "Case Siegfried," but Hitler no longer wanted to commit himself by choosing invincible mythological heroes as patrons for his military operations since the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa had let him down. Hitler kept interrupting Halder with all kinds of questions. The conversation time and again went off at a tangent, but after three hours Hitler eventually gave his consent to the basic outline of the plan. This then was the scheme:

Act 1: Two Army Groups to form a huge pair of pincers. The northern jaw of the pincers to advance from the Kursk-Kharkov area down the middle Don to the south-east, while the right jaw of the pincers drives rapidly eastward from the Taganrog area. West of Stalingrad the two jaws to meet, enclosing the bulk of the Soviet forces between Donets and Don, and annihilating them

Act 2: Advance into the Caucasus, that 700-mile-long range of high mountains between the Black Sea and the Caspian, followed by the conquest of the Caucasian oilfields.

It was noon when Halder left the "Wolfsschanze" to drive back to the Mauer Forest.

He was weary and depressed, full of doubts and irritated by Hitler's know-it-all manner. But he nevertheless felt that he had won Hitler over for a plan that was at least practicable—a plan which used the German forces economically and which went for the objectives on the southern front a step at a time, with clearly defined strong points. If it came off, Stalin would lose the entire Caucasus, including Astrakhan and the Volga estuary—in other words, the overland as well as the shipping link with Persia. The southern objective of "Operation Barbarossa" would thus have been reached.

All that remained was to formulate the project into a clear directive for the separate branches of the armed forces.

Seven days later, on 4th April 1942, Colonel-General Jodl submitted his draft directive. The Armed Forces Operations Staff had solved the problem in the traditional German Staff manner: they had begun by briefly outlining the situation, by listing the objectives as separate "tasks," and, in this way, leaving considerable freedom to the Commander-in-Chief Army Group South, Field-Marshal von Bock, as to the actual execution of the vast operation. That had been a General Staff tradition for 130 years, from Scharnhorst to Schlieffen and Ludendorff.

But this High Command draft of "Operation Blue" was shot down almost at once.

During the critical situations of the past winter Hitler had lost faith in the loyalty of his generals. Commanders-in-Chief and Corps commanders had often left no doubt that they were obeying his orders unwillingly. Following Brauchitsch's spectacular departure, Hitler had himself assumed supreme command of the Army, and he was not prepared now to have his authority diminished by "elastically framed tasks."

When he had read the draft he refused to give his consent.

The plan, he argued, was leaving the Commander-in-Chief South far too much freedom of action. Hitler was not having any elastic directives. He demanded detailed instructions. He wanted to see the execution of the operation laid down minutely to the last detail. When Jodl demurred Hitler took the papers out of his hand with the words: "I will deal with the matter myself."

On the following day the result was available on ten pages of typescript—"Fuehrer Directive No. 41 of 5th April 1942," Alongside Plan Barbarossa, Directive No. 21, this new directive became one of the crucial papers of the Second World War, a blend of operational order, fundamental decisions, executive regulations, and security measures.

As this directive was not just the plan for another gigantic military campaign, but also the detailed time-table leading to Stalingrad—a document, in fact, which already contained in itself the turning-point of the war—its most important passages are worth quoting here.

Right in the preamble we find a bold claim: "The winter battle in Russia is drawing to its close. The enemy has suffered very heavy losses in men and material. In his anxiety to exploit what seemed like initial successes he has spent during this winter the bulk of his reserves earmarked for later operations."

Proceeding from this thesis, the Order went on: "As soon as weather and ground conditions permit the German Command and the German forces, being superior to the enemy, must seize the initiative again in order to impose their will upon the enemy. The aim is to destroy what manpower the Soviets have left for resistance and to deprive them as far as possible of their vital military-economic potential."

This is how Hitler saw the execution of the plan: "While adhering to the original general outline of the campaign in the East, the task now is for the centre of the front to hold back temporarily . . . while all available forces are concentrated for the main operation in the southern sector, with the objective of annihilating the enemy on the Don and subsequently gaining the oilfields of the Caucasian region and the crossing of the Caucasus itself."

On the detailed execution of the campaign the directive stated: "It is the first task of the Army and Luftwaffe after the period of mud to create the prerequisites for the execution of the main operation. This entails the cleaning up and consolidation of the entire Eastern Front and the rearward military areas. The next tasks will be the clearing of the enemy from the Kerch Peninsula in the Crimea and the capture of Sevastopol."

A key problem of this extensive operation was the long flank along the Don. To avert the threat resulting from it Hitler took a fatal decision which did much to precipitate the disaster of Stalingrad. This was what he ordered: "As the Don front becomes increasingly longer in the course of this operation it will be manned primarily by formations of our Allies. . . .These are to be employed in their own sectors as far as possible, with the Hungarians being farthest north, then the Italians, and then, farthest to the south-east, the Rumanians."

So much for grand strategy and theory.

As for the practical execution, this was to start with "Operation Bustard Hunt" in the Crimea. In his book The Most Important Operations of the Great Fatherland War the Soviet military historian Colonel P.A. Zhilin has the following to say about the situation in the Crimea in the spring of 1942: "The stubborn fighting of the Soviet troops and the Black Sea Fleet yielded us much strategic advantage and foiled the calculations of the enemy. The German Eleventh Army, tied down in the Crimea, could not be used for the attack against the Volga and the Caucasus."

That is entirely correct. And just because it was of such importance to the Soviets to keep Manstein's Eleventh Army immersed in the Crimea, Stalin had mobilized a formidable force for this task. Three Soviet Armies—the Forty-seventh, the Fifty-first, and the Forty-fourth—with seventeen rifle divisions, two cavalry divisions, three rifle brigades, and four armored brigades, were blocking the 11-mile isthmus of Parpach, the passage from the Crimea to the Kerch Peninsula. Kerch in turn was the springboard to the eastern coast of the Black Sea, and hence into the foothills of the Caucasus.

Every mile of this vital neck of land was being defended by approximately 16,000 men—more than nine men to each yard.

The Soviet forces were established behind an anti-tank ditch 11 yards wide and 16 feet deep which ran across the entire width of the isthmus. Behind it extensive wire obstacles had been erected and thousands of mines laid. Massive girder-like structures, made of rails welded together like bristling hedgehogs, protected machine-gun posts, strong-points, and gun emplacements. With water on both sides of this 11-mile front, all possibility of outflanking was ruled out.

Next-Prelude To Case Blue-Conquest Of The Crimea

This is a part of WWII that is rarely mentioned - the Dutch actually took part. Apparently their forces in Java lasted longer than in Europe. Is this true?

It is true. Germany moved into Holland on May 10th, 1940. Though there were skirmishes between Dutch and German forces as late as May 16th, they officially surrendered on May 14th, just 4 days later.

On Java alone the Dutch held out for 8 days, finally surrendering on the Morning of March 8th.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.