Posted on 12/02/2012 5:48:09 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1942/dec42/f02dec42.htm

American General sacked in New Guinea

Wednesday, December 2, 1942 www.onwar.com

General Harding [photo at link]

In New Guinea... The Australians capture a portion of the Japanese defenses at Gona. A Japanese convoy carrying reinforcements is diverted by air attacks, but manages to land its troops along the coast to the west. General Eichelberger, sent by General MacArthur to investigate the lack of progress at Buna, decides to relieve General Harding of command of the US forces there.

In the United States... The first manmade self-sustaining chain reaction is achieved in the atomic pile at Chicago University.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/frame.htm

December 2nd, 1942

UNITED KINGDOM: Aircraft carrier HMS Pioneer laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

Sloop HMS Cygnet commissioned.

Submarine HMS Sickle commissioned.

Minesweepers HMS Fancy and Espielgle commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

ENGLISH CHANNEL: ASW trawler HMS Jasper torpedoed and sunk by the German motor torpedo boat S-81. (Dave Shirlaw)

BELGIUM: Members of the Rexist (fascist) movement are asked to help Germany by spying.

GERMANY: U-320, U-792, U-793, U-804, U-927 laid down. (Dave Shirlaw)

ITALY: Rome: Mussolini reveals that 40,000 Italians have been killed in action, 86,000 wounded and 231,000 taken prisoner since the war broke out.

MALTA: A British naval squadron was guided to its target tonight by RAF aircraft dropping flares over a convoy carrying tanks and 2,000 troops from Sicily to North Africa. Once it had made contact, the squadron - three light cruisers, HMS AURORA, HMS ARGONAUT and HMS SIRIUS, with the destroyers HMS QUENTIN and HMAS QUIBERON - attacked from the darkness using RDF [radar]. All four enemy ships and an escorting destroyer were sunk.

HMS QUENTIN was later sunk by Italian torpedo planes off Galita Island at 37 40N, 08 55E. HMAS QUIBERON picked up survivors. (Alex Gordon)(108)

TUNISIA: Allied troops beat off a German attack on Tebourba but lose forty tanks.

ABYSSINIA: Ethiopia declared war on Germany, Italy, and Japan. (Dave Shirlaw)

NEW GUINEA: Australian troops capture part of the Japanese positions at Gona.

US General Eichelberger is sent by MacArthur to find out about the lack of progress at Buna, New Guinea. He will decide to relieve General Harding.

Allied air superiority forces Japanese reinforcements trying to land at Buna to land further west.

AUSTRALIA: Vice-Admiral Carpenter USN sends the Dutch destroyer Tjerk Hiddes from Fremantle to Darwin, thence to Portugese Timor to take off the men of Sparrow Force. (William L. Howard)(188, 189, 190, 191)

Minesweeper HMAS Armidale hit by two torpedoes from Japanese torpedo aircraft and sank within five minutes in position 10°S, 126°30´E. while on its second journey to Timor to evacuate refugees and bring relief personnel from Port Darwin. 40 of her crew perished along with 60 Dutch passengers. (Dave Shirlaw)

CANADA: Frigate HMCS New Glasgow laid down.

Corvette HMCS Oakville completed refit Halifax , Nova Scotia.

Fairmile depot ship HMCS Provider commissioned.

Tug HMCS Glenlea laid down Owen Sound, Ontario.

(Dave Shirlaw)

U.S.A.: At the University of Chicago; the first manmade, self-sustaining atomic chain reaction is achieved. In a squash court under the university football (American) stadium a group of scientists led by the Italian physicist, Enrico Fermi, allowed the “pile” of uranium, moderated by graphite rods, to run for four and a half minutes, which produced just one half-watt of power, but proved man can control atomic power.

Scientists waited in awe as the neutron counter clicked faster. Then Fermi raised his hand. “The pile has gone critical,” he said. Someone telephoned Dr. James Conant, the head of defence science in Washington. “Jim,” he said, “the Italian navigator has just landed in the new world.”

Two prototype examples of the Beechcraft Model 28, are ordered. These will be known as the XA-38-BH Grizzly, USAAF s/ns 43-14406 and 14407. The aircraft were designed to deliver knock-out blows to fortified gun emplacements, AFVs and surface ships. Beech designed them to be highly manouverable and be able to absorb heavy battle damage. The main armament was a 75mm T15E1 cannon in the nose fitted with a Type T-13 automatic feed mechanism with 20 rounds of ammunition. (Jack McKillop)

During WW II, the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) produced numerous documents, most commonly known are the Intelligence Bulletins. The Military Intelligence Special Series continues with “Enemy Air-Borne Forces.” (William L. Howard)

Minesweeper USS Captivate launched.

Frigate USS Asheville commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

ATLANTIC OCEAN:

U-508 sank SS Trevalgan.

U-375 damaged HMS Manxman. (Dave Shirlaw)

From an article on page 1:

“Joint Committee on Reduction of Non-essential Federal Expenditures”

Whatever became of that committee? I can only guess.....

No consideration of the winter fighting would be complete without some mention of the battle of Velikiye Luki, the ancient fortress in the vast swampy region north of Vitebsk between Lovat and Western Dvina.

A beautiful old town, with 30,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the War, Velikiye Luki used to attract Intourist parties with its folklore. Velikiye Luki began to play an important part during the German offensive battles of 1941 and continued to do so during the first Soviet counter-offensive from the Moscow region. The Lower Saxon 19th Panzer Division, parts of the Hessian 20th Panzer Division, and the infantrymen of 253rd Infantry Division had taken the town by storm in August 1941 after heavy fighting.

Four and a half months later the first Soviet offensive was launched against the fortress in the swamp.

On 9th January, 1942, Colonel-General Yeremenko and General Purkayev drove their striking armies across the chain of lakes from Ostashkov against Vitebsk, with a view to gaining the vast area to the west of Moscow by means of an enveloping attack and to annihilating the German Army Group Centre which stood poised for its leap to Moscow. But the Soviet thrust was halted by the German infantry in desperate fighting. It spent its force against the breakwaters of Kholm, Velizh, and Velikiye Luki.

Parts of the 83rd Infantry Division, hurriedly switched from France to Russia, were defending the "city in the swamp", the fortress astride the vital routes from Leningrad, Kiev, and Moscow to Belorussia and the Baltic. Throughout the summer of 1942 the Soviet Third Striking Army again and again tried to break the defenders of Velikiye Luki with sudden and heavy artillery bombardment. However, the German 277th Grenadier Regiment under Colonel von Rappard fortified its positions. Supplies were difficult as there was no such thing as a continuous front along either side of Velikiye Luki.

On the northern side, especially towards Kholm and the Lovat, there were only weak pickets. Only just south of Kholm did a continuous line start again, held by 8th Panzer Division. But the division staff had to watch in amazement how, immediately south of them where the front abruptly ended, the Russians were recruiting young men in the hinterland with complete impunity, driving away all livestock and collecting any useful material. In this situation a vital part was played by the German armored trains—the armored train No. 3 from Munich and the auxiliary armored train No. 28. Without them it would have been impossible; to get supplies through to Velikiye Luki.

On 19th November, 1942, the second great Soviet winter offensive began on the southern front, with the main weight at Stalingrad and on the Don. On the northern front, meanwhile, Soviet large-scale attacks were designed to tie down the German forces and sweep away those irritating German breakwaters in the Vitebsk area. The Soviet Third Striking Army was to get into Vitebsk at long last. But in order to take Vitebsk it would first have to capture Velikiye Luki.

General Purkayev attacked the town with three divisions.

Three divisions against one regiment.

The Soviets thrust past Velikiye Luki in the north and south, through the chain of strongpoints of 83rd Infantry Division, and encircled the town. Inside the fortress were 7500 German troops under Lieutenant-Colonel von Sass, defending a front line of thirteen miles.

They were grenadiers, gunners, engineers, baggage and medical units of 83rd Infantry Division. They were reinforced, or had simply been joined by the following units who found themselves inside the " fortress " after their retreat: railway engineers and construction units, Nebelwerfer units of the 3rd Mortar Regiment, and Light Observation Battalion 17, a German local defense battalion, and a battalion of Estonian volunteers, composed of Estonians who, in the course of the fighting, had come over in bulk from the Red Army. There were, moreover, three troops of Army Flak Battalion 286 and a troop of light flak, as well as the heavy mortars of 2nd Troop, Army Artillery Battalion 736, the 3rd Battalion, 183rd Artillery Regiment, and parts of the 70th Motorized Artillery Regiment.

A miniature Stalingrad.

General Purkayev naturally wanted to take the town by storm. But the attempt miscarried. He thereupon started to batter it systematically by artillery and aerial bombardment. Day after day this pounding continued. Building after building, bunker after bunker, street after street were reduced to rubble. Fire gutted the ruins.

The German defenders of Velikiye Luki received their meagre supplies of food and ammunition from the air. Because too many of the dropped supplies were coming down among the enemy lines outside the small combat area of only seven square miles, Stukas were used to deliver the supplies for the first time in the War. For that purpose the Sixth Air Fleet had organized a mixed operational formation. It was led by Heinz-Joachim Schmidt, the Commodore of 4th Bomber Geschwader. He was based, together with his operations staff, at the Great Ivan Lake in order to be as near as possible to the threatened town. In spite of the great superiority which the Russians had in the air and in spite of their anti-aircraft defenses all round the fortress in the swamp, the flying formations did everything in their power to drop their " supply bombs " accurately into the progressively shrinking dropping area. Food and ammunition containers as a rule hit the target accurately. Nevertheless, supplies soon had to be curtailed by 25 per cent and later had to be cut down by half.

On 13th December, after a heavy barrage, four rifle divisions and an armored brigade under General Purkayev mounted their general attack on the western part of the city.

There was savage fighting for the bridge over the Lovat. This was held by Lieutenant Albrecht with his column of engineers against a tenfold Russian superiority. Time and again the Russian companies penetrated into the small German bridge-head. Each time they were dislodged in hand-to-hand fighting with trenching tools, bayonets, and hand-grenades. Lieutenant Albrecht was seriously wounded. Shot through the throat he lay at his post but continued to direct the defensive fighting of his engineers.

On the second day of Christmas, 26th December, 1942, the Soviets attacked with strong armored forces from the south and south-west. In fierce house-to-house fighting they forced their way right across the town on a narrow front.

The defenders' heavy infantry weapons and anti-tank guns were eliminated one by one. In this way the German strongpoints were rendered almost helpless in the face of the enemy tanks. The Soviet rifle battalions fought with outstanding gallantry. In particular the Komsomols, fanatical young communists, distinguished themselves by their devotion to duty throughout the next few weeks. Private Aleksandr Matrosov of the 254th Guards Rifle Regiment earned the title of Hero of the Soviet Union by sacrificing his life.

Matrosov put an end to his company's heavy losses outside a German bunker whose machine-gun had been pinning the Russians down and exacting a heavy toll from them. Matrosov crept up to the bunker's firing slit, covered it with his body, and thus blocked the view of the bunker's crew. Matrosov held on to the machine-gun barrel, and his fingers were still gripping it tight when he had long since died. His company used the pause in the fire to storm the bunker.

At the beginning of 1943 there were only two strongpoints left in the frozen swamp—the Citadel and the railway station.

The Citadel was held by Captain Darnedde, commanding the Field Depot Battalion of 83rd Infantry Division. With 427 men he defended an area of no more than 100 by 250 yards. At the railway-station, in the eastern part of the city, Lieutenant-Colonel von Sass with 1000 men was holding the wrecked railway installations and the barracks. The troops were hoping to be relieved. It was that hope that kept them going—in spite of biting cold and a gnawing hunger. Out of forty-five supply containers dropped over their positions only seven had reached their target. The three hundred horses originally in the city had long been eaten. There was only one loaf of bread for every ten men per day. Twenty men had to share one tin of meat.

It is scarcely imaginable for us today what these men went through. Without sleep, without the least bodily care, full of lice, filthy and starving, they yet fought on. Some 3000 shells crashed down on them each day. They had no time to move their dead out of the way. The wounded lay among the wreckage, only scantily looked after. Drinking water had to be brought in, under danger of death, from a pond outside the ramparts. And in that pond lay a knocked-out Soviet tank with its dead crew.

But where was the main German line?

Was nothing done to relieve the encircled city?

The attempt was made all right. But once again it was a case of inadequate forces.

The first on the spot was General Brandenberger's 8th Panzer Division. The regiments of this Berlin-Brandenburg division—which had always been employed in the East, and which had its own peculiar character owing to its many Baltic officers—had just abandoned its positions south of Kholm. It was to have been taken to the Stalingrad area by train. However, this laudable intention had to be cancelled in view of developments on the division's own doorstep.

On the evening of 21st November 8th Panzer Grenadier Regiment received an order by telephone:

"The regiment will mount an immediate attack against the enemy advancing west of Velikiye Luki who has already crossed the Leningrad-Odessa railway. The regiment will thus save Novosokolniki."

"Save" was the actual word.

Novosokolniki, a rear base and centre of field hospitals, was already being attacked by Soviet tank battalions and a motorized brigade. It was being defended by supply units of 3rd Mountain Division under Colonel Jobsky.

On the following morning the regiment made contact at Gorki with unsuspecting enemy forces and succeeded in dislodging them. On the following day the division's two Panzer Grenadier Regiments fought their way to the east: 28th Regiment under its commander Lieutenant-Colonel Baron von Wolff, stormed the high ground east of Gorki, and 8th Regiment attacked in the direction of Velikiye Luki.

Captain Bernd von Mitzlaff's 2nd Battalion, 8th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, reinforced by a dozen captured tanks, dislodged the Soviets and took the village of Glazyri. Things had now begun to move. Major Schmidt was containing the enemy with what few armored fighting vehicles 10th Panzer Regiment possessed. Mitzlaff's battalion stormed the high ground east of the village.

In the distance they could see the spires of Velikiye Luki.

Once again the moment had come where that decisive battalion was lacking which might have tipped the balance. Schmidt's tanks were out of ammunition. The 1st Battalion was still hanging back. The 2nd Battalion had to regroup for defense. Soon the enemy had rallied again. The Soviet regiments mounted their counter-attack. Once more Colonel von Skotti's well-tried 80th Artillery Regiment came to the rescue. Skotti again proved himself a past master in directing and concentrating his regiment's entire fire-power. The gunners bore the brunt of the fighting since at that time 8th Panzer Division possessed anything but adequate armor. It was equipped with captured Russian tanks, some Czech Skoda-38 fighting vehicles, and a few German Mark IVs. The battalions were halted.

Even the intervention of Combat Group Jaschke with parts of the Hamburg 20th Motorized Infantry Division and the 291st Infantry Division could not change the situation. The first attempt to reach the encircled city of Velikiye Luki in one smooth move from the north-west had failed.

There was only one kind of help which Colonel von Skotti was able to give the beleaguered city—he ordered his long barrel troops to move up to the front lines and pounded General Purkayev's regiments of the Third Striking Army as they were pressing against the city.

Preparations for a relief attack from the south-west were meanwhile under way. While General Kurt von der Chevallerie with the divisions of his LIX Corps was holding a cover line around Vitebsk, General Wöhler, the former Eleventh Army Chief of Staff, formed a relief group which got to within six miles of Velikiye Luki by 24th December. Combat groups of 291st and 331st Infantry Divisions, parts of the reinforced 76th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, of 10th Panzer Regiment, and of Assault Gun Battalion 237 pushed this relief wedge via Novosokolniki to within sight of the encircled city. But there the troops and vehicles, having suffered exceedingly heavy losses, got stuck in the deep snow. Yet Wöhler did not give up.

The Austrian 331st Infantry Division under Lieutenant-General Dr Franz Beyer eventually got to within two and a half miles of the western edge of Velikiye Luki. But they did not get beyond that point.

A mere two and a half miles! No distance at all—but the distance between heaven and hell.

One last attempt was made on 9th January. A combat group under Major Tribukait, the commander of the Jäger Battalion 5, mounted an attack against the fortress with tanks, assault guns, and armored infantry carriers. The few infantry carriers belonged to 8th Panzer Division, the tanks were from 1st Battalion, 15th Panzer Regiment, and the assault guns from the reinforced Panzer Battalion 118.

"Keep moving and firing!" had been their order.

Don't stop.

The crews of knocked-out vehicles were to climb on to the outside of others without halting. With this method of "keeping going and firing" Tribukait did in fact succeed in piercing the strong enemy ring. A number of tanks and infantry carriers were lost, but the group got through.

It was exactly 1506 hours when Darnedde's half-starved men saw the tanks from the ramparts of the Citadel. They wept with joy and fell into each other's arms. "They've done it!" they kept shouting, "They've done it!"

Fifteen armored fighting vehicles clanked into the courtyard of the Citadel; they included the last three tanks of 1st Battalion, 15th Panzer Regiment, under Lieutenant Koske. But the fortunes of war had turned against Darnedde's battalion.

As soon as the overrun Russians realized the Germans had broken through they concentrated their artillery and furiously pounded the area of the Citadel

Tribukait immediately ordered his tanks to get out of the confined yard among the ruins, to which there was only one approach. But everything seemed to conspire against him. Just as one of the fifteen tanks was passing through the entrance in the ramparts it received four direct hits and remained lying motionless, its tracks shot to pieces.

Tribukait's small force was now in a trap and became the target of furious Russian shelling by guns of all calibres. One tank after another fell victim to the Soviet bombardment. It was an unprecedented disaster.

Tribukait's surviving Jägers and tankmen joined the defenders in the role of infantry.

On 15th January a parachute battalion made an attempt to get into the Citadel.

But that attempt failed too.

Disaster came to the eastern part of Velikiye Luki on 16th January. There was diphtheria inside the " Budapest " strongpoint.

The building containing the command post of 2nd Battalion, 277th Infantry Regiment, and the dressing station with three hundred wounded was blazing. Russian tanks were outside. At that point Major Schwabe gave up.

Lieutenant-Colonel von Sass likewise surrendered in his wrecked command post.

When General Wöhler received the signal informing about their situation he decided to put an end to the tragedy inside the Citadel. He radioed to Major Tribukait who, as the senior officer, had been in command since 9th January:

"The defenders will fight their way out westwards to their own lines."

The defenders will fight their way out—all well and good. But what about the wounded?

Tribukait consulted with Darnedde. They concluded that the wounded would have to be left behind.

To avoid panic the break-out was kept secret from them. Only the medical officer and four medical orderlies who were to stay behind with the wounded and share their ominous fate were let into the secret. Captain Dr Wehrheim, the medical officer, was handed a sealed letter only to be opened two hours after the break-out.

At 0200 at night the defenders assembled. There were only 180 men left. They all knew what was at stake. And they moved off with the kind of determination shown only by men doomed to death. They broke through three Soviet lines. They knocked-out an anti-tank gun and two machine-gun posts. They overran the crew of a Soviet strongpoint and at 0530 hours eventually arrived at the German main defensive line with seven prisoners.

The wounded in the Citadel, of course, had discovered what was up.

Eyes wild with fear they had listened to every noise. They had heard the words of command. (it was no secret to German troops what happened to wounded prisoners who had the misfortune to fall into Soviet hands). And as the silence of terminated battle crept through the basements a ghostly operation began: thirty casualties who believed they could just about keep on their feet set out under the leadership of a lieutenant and a sergeant.

Eighteen of them reached the German lines after a frightful journey.

Subsequently a third group also made its way back to the German positions.

Altogether eight men made their escape from the eastern part of Velikiye Luki and, after the most incredible adventures, fought their way through to the German lines. Eight out of a thousand.

One of them was Lieutenant Behnemann, commanding 9th Troop, 183rd Artillery Regiment. The story of his journey through the enemy lines is one of those dramatic Odysseys from the chronicle of escapes which constitute a special chapter of the war in Russia.

It is worth recording here.

The date was the 13th January and the time 1900 hours.

A few centers of resistance were still holding out among the railway sidings. Lieutenant Behnemann counted the men in his bunker. There were forty-one left. Twenty of them were seriously wounded and were lying on the floor and on bunks. The men were a sorry sight. For nights on end they had stood in the trenches, a little cold coffee substitute in their flasks and one-seventh of a loaf of bread in their knapsacks—their daily ration.

At 2200 contact was lost with the observation post. The sentry who had just been relieved at the blockhouse next to the bunker came in and reported: "OP and Battalion HQ are being shot up by a Soviet tank. They're both blazing."

Clearly, the end had come for Major Hennigs, the artillery commander of Velikiye Luki. Less than twelve hours previously he had rung through to the bunker: "You hold the bunker, Behnemann! I'm hanging on to the OP."

The men were dozing. The air was thick enough to cut. The wounded were moaning. The medical orderly had no morphia left for them and no dressings. At daybreak, towards 0700, Behnemann went across to the small blockhouse to have a look for himself. Things were getting critical. The house was more or less destroyed. In its floor a shell had torn a deep hole. It was possible to get through that hole, under the floor, and watch events outside through the wrecked external wall. Behnemann could see clearly that the OP was in Russian hands. Obviously they were about to storm the bunker.

A T-34 was already slowly moving up alongside the trench. Behnemann was watching it.

And thus he missed what was happening behind him. Suddenly there was a noise.

Orders shouted in Russian. Shots.

The Soviets had reached the blockhouse and the bunker from the other side. Behnemann rolled under the floorboards. Less than two feet away from him, along the outer wall, were Russian soldiers.

They were tossing hand-grenades at the door and firing their sub-machine-guns through the firing slits of the bunker.

A German voice shouted from the bunker entrance: "Don't shoot— we surrender. We're all wounded!"

A Russian replied in German: ("Come out!" The bunker door opened. Behnemann's men reeled out, their hands up.

"Where guns?" the Soviet NCO asked the first German. He nodded his head towards the bunker. "Get them, quick, quick," the Russian shouted. The men about-turned and brought out their weapons and ammunition. By then an interpreter arrived on the spot. He ordered the prisoners to get into the blockhouse with raised hands. Behnemann crept even farther away from the hole in the floor and pressed himself into a corner.

Overhead the interrogation began.

"Officer?" was the first question, as always.

Then: "Occupation?"

Whenever the answer was "worker" the interpreter said: "Good."

"Peasant? Good."

One of them replied: "Office worker." And the interpreter said: "Also good."

One question asked repeatedly was: "Photo?" What was meant was a camera. But only one German NCO possessed this coveted article. After the interrogation the prisoners were made to jump down into the trench. "Quick, quick!" Then they were marched across to the "Red House". The wounded had flung woolen blankets over their shoulders and were staggering along the trench. There was no ill-treatment.

But there was that ceaseless shouting: "Davay, davay—quick, quick!" Accompanied by a nervous and menacing clicking of rifle bolts.

All day long Behnemann lay under the floor of the blockhouse. In the early afternoon a long column of prisoners was marched through the old firing pit. Something like 500 or 600 men. They were a sorry sight. A few officers were reeling through the snow in stockinged feet.

Their felt boots had been taken away.

"Anything rather than that," Behnemann thought. "Anything."

At that moment the man from Visselhövede in Lower Saxony made up his mind. Captivity was not for him. He had no map—only a pocket compass. And in his pockets he had a pistol with eight rounds. And his daily ration—one-seventh of a loaf of bread. That was his whole equipment. Would it be enough to cross the vast swamp and reach the German lines?

The time was 1930 hours. The first night of Behnemann's escape was beginning. He crawled out of his hiding place. He swung himself out of the window. He boldly walked upright down the trench and then let himself roll down the slope to the right. The ruined scenery was steeped in an eerie light by the brilliant moon. The frozen snow crunched and cracked under his felt boots.

Careful now.

Behnemann had reached the spot where the Russians had cut through the barbed-wire fence to lead their prisoners through. That was where Behnemann wanted to slip through too.

"Stoy," a voice called.

Behnemann continued running. Another shout: "Stoy!"

Damn.

He flung himself into the snow. For half an hour he acted a dead man. Then he crawled on, working his way through the wire.

Suddenly there was activity all round him. Russian soldiers were rounding up loose horses and driving them in the direction of Maksimovo. That was a piece of luck. A single man moving along the edge of the herd of horses would not attract attention. Behnemann hurried on.

Suddenly he started:

surely there was something crouching in the snow.

Motionless. Cautiously he approached it —a dead German soldier. Fifty yards on—another. Frightful markers along the road. Every thirty or fifty yards was another lifeless soldier. Sagged over forward. Or wrapped in a blanket. Or fully extended in the snow. All of them clearly wounded men who had wanted to take a moment's rest on their march into captivity and in doing so had frozen to death. Not until a good way farther down did the terrible signposts come to an end. Behnemann was walking briskly. The night was bright and silent. He glanced at his compass. Four days earlier he had taken a bearing on the triangulation point two and a half miles north-west of the city. That was where he was now making for. Sleigh tracks crossed the swamp in all directions. Behnemann had to dodge into the scrub whenever a Soviet sleigh column approached.

After two and a half miles he reached the triangulation point. He scuttled across the first big supply route from east to west. He was to cross another six or eight such compacted snow roads in the course of that night. Alongside the road or on the ridges of clear snow ran Russian field telephone cables. During that first night Behnemann cut many of them with his pocket knife. After that he no longer bothered.

There was not much traffic. He encountered only about twenty vehicles, all of them driving confidently with unmasked headlights. They, of course, had nothing to fear from partisans. By 2400 hours Behnemann had reached the frozen Lovat river. He had to cross it. On the far side, parallel with the river, ran the road from Nevel to Staraya Russa. He kept on to the north. Around 0500 he crossed the Nesva. And then the last east-west highway near the village of Molodi. Behnemann knew it from observation through his trench telescope: it was the only village which stood out from the swamp forest. Day was breaking. And daytime was the enemy of wild beasts and men on the run. He had to find a hideout. He found it a hundred yards beyond the road—a willow thicket over six feet high. A day is a long time. And at twenty degrees below zero Centigrade, when one had to stay put in the same spot, it was positively unending. The lieutenant counted the trees around him. He estimated distances and every half-hour he performed ten knee-bends. Then, for a change he would "mark time at the double", or else beat his arms round his body.

Dusk fell at long last. It was twenty-four hours since he had set out. He had only slept standing up and had sucked snow to assuage his thirst. To cope with his hunger he had eaten small pieces of bread. He never broke off more than a minute piece and then took a long time chewing it. The bread pulp went all sweet in his mouth if he chewed it long enough. Above all, he must not be in a hurry to swallow it. Progress during the second night was particularly laborious. First his route lay through a thick forest deep in snow. Then across a flat swamp with tall tufts of reed and thick patches of willow. Wearily Behnemann moved on, and for the second time came upon the Nesva river. And then it happened. He slipped, rolled down the steep bank, and struck the ground with his head. He got to his feet in a daze. He caught his breath. Immediately opposite, on the far bank of the frozen stream, was a Soviet sentry eyeing him curiously. The Russian worked his rifle-bolt to get a round in the breach. But he did nothing else.

Behnemann stood rooted to the ground. One minute passed. Two minutes. A second Russian appeared on the far bank. The two exchanged a few words.

The new man ran down the far bank and shouted: "Parol!"

That meant the password.

Behnemann cut and ran. The bullets sang past him. He scrambled up the bank. He raced, panting, towards a ditch. He flung himself into it. He pressed himself firmly to the ground. There were voices around him everywhere. "They'll find you, they'll find you," he kept saying to himself. But they did not find him. The moon set. Now it was dark. That was what saved Behnemann. When the noise had died away, he moved on, now to the west. He had set his compass to 40—the direction of a conspicuous star. He kept to this course.

He was enveloped by a dark, thick forest. The zig-zagging trails of animals in the deep snow were the only sign of life. Behnemann followed the trails. Here there was no need to be afraid of encountering a human being. He therefore continued to push on even after daybreak. At 0800 he was at the edge of the forest. He was surrounded by tall reeds. Slowly he moved forward, step by step. Suddenly there were voices. Cautiously, he peered through the reeds. He caught his breath. He was right in the middle of a line of Soviet sentries, established in front of the thick reeds. Every two hundred yards a machine-gun. In front and in between them were sentries with rifles. He crawled and rolled into a snowy hollow. From there he observed. He chewed his last piece of crust and swallowed several handfuls of snow. Hours passed. The cold tingled through his skin, and crept over his body like icy fingers. It lay heavily on his brain and on his heart. His breath was slow. Behnemann counted his pulse beat. It was forty-five. Near the danger-point of freezing to death.

At 1700 hours the Russian sentries on the edge of the reeds were relieved. Here was his opportunist Ducking low, Behnemann pushed ahead between the sentries. But in the bright moonlight there could be no hope of slipping through the front line. At the same time he lacked the strength to crawl back. Regardless, he walked back upright. He turned north. From somewhere on his right came a shout: "Parol!" He paid no attention. There was a crack of carbine fire. And three short pursts from a machine-gun. He crossed the open ground, avoiding the thickets where the sentries were posted. He had walked for a little over a mile when he suddenly found himself in the middle of the Russian main defensive line. All round on the high ground he was able to make out the course of the front. Machine-gun fire towards the west enabled him to discern the positions. Bent double, he ducked and slipped through the lines. He lost his gloves. He tore his cap in two and wrapped the bits of cloth round his hands so they should not get frost-bitten with all that flinging of himself down in the snow.

His strength was now failing fast. He was talking to himself, semi-audibly. "I can't go any farther," he said and collapsed. But a moment later he picked himself up again: "I can manage a little way yet!"

This was repeated every half hour. Always he remained in the snow just to that danger-point where indifference may mean death. But each time he forced himself up again. He followed the tracks of the hares, running straight towards the moon, towards the west. From 0200 onwards the planet Venus fixed his direction for him. At 0400, at the end of the third night and the beginning of the third day, he suddenly found himself in front of a barn. There was hay inside. He flung himself down. Sleep!

But hunger, thirst, and the fear of freezing to death stopped him from getting more than two hours' feverish dozing. Then he pulled himself up again. He could not die here in this hay. He had to get out. He stepped outside. The grey dawn was all round him. He reeled on. He saw some farmhouses.

"Parole!" someone shouted.

Let them shout. He moved on, unconcerned. Ten paces. Twenty. Then something flashed in his brain: What did that voice say? Parole? That final "e"—surely that was not part of the Russian word?

Could it be ...?

immediately west of Velikiye Luki, was in German hands. He knew that for certain. The last battle reports he had listened into at his OP had reported that this sector of railway had been crossed and secured in a relief attack by a combat group of 8th Panzer Division. No point in hesitating. He was finished one way or another. So he turned about and reeled back to the farmhouses, to human habitations. He reached an isolated peasant hut. He drew his pistol. He knocked. An old man opened the door.

He stared at him.

Behnemann pointed outside: "Germanski soldier or Ruski soldier?"

The old man shook his head: "Germanski."

And he pointed across to, a stone-built house. Behnemann staggered out of the door. He dragged himself across. His lips trembled as he spelt out for himself the tactical sign on the door: 5th Troop, 80th Panzer Artillery Regiment. "The 8th from Cottbus," he muttered. He knew the famous 3rd Light Division; which in 1940 had been transformed into 8th Panzer Division and had proved its value as an armored formation on the northern and central fronts.

He reeled through the door, into the big room which housed the command post.

The troops looked up startled as they caught sight of the spectre in the door—an emaciated figure, one hand wrapped into the hood of his camouflage cape, the bearded face disfigured with frost boils.

They sat as if turned to stone.

The ghost-like visitor stared fascinated at the iron stove. And at the white enamelled German Army can in which coffee substitute was being heated.

He picked it up. He raised it to his lips and drank. He kept on drinking. Then he put it down. And only then did he utter his first words:

"I've come from Velikiye Luki."

Then the others leapt up and pushed a chair under him. He dropped into it and laughed and laughed.

His tears were streaming down his frozen white face. He had been on the go for sixty hours. In the icy cold he had walked twenty-five miles. And they had not caught him. He had escaped from the hell of Velikiye Luki—he, Lieutenant Behnemann of 9th Troop, 183rd Artillery Regiment.

Thus Behnemann escaped captivity and the revenge which a fanatical Soviet leadership was later to take for the defeats of Velikiye Luki.

After the War they picked out from their P.O.W. camps the German troops who had fought at Velikiye Luki; took them back to the fortress and there tried them by court martial. One man of each rank was sentenced to death by hanging—one general, one colonel, one lieutenant-colonel, one major, one captain, one lieutenant, one top sergeant, one sergeant, one senior corporal, one corporal, and one private.

On 29th January, 1946 the men were publicly hanged in Lenin Square in Velikiye Luki. Among them were the commander of 277th Infantry Regiment and the former town commandant, company commanders, railway officials, junior commanders, and rankers. All others who could be rounded up were sentenced to twenty or twenty-five years' imprisonment. Only eleven of them survived to return to Germany between 1953 and 1955.

That was Velikiye Luki, one of the focal points of the winter battle of 1942-43.

While compelling, and sad commentary on the human struggle from a Christian perspective, it is difficult to feel sorry for those that donned the Nazi mantle. Look to Jasenovac for what they did to my people.

The Times headline for January 2 is “Russians Capture Velikiye Luki, Vital Base.” I see that will be slightly premature.

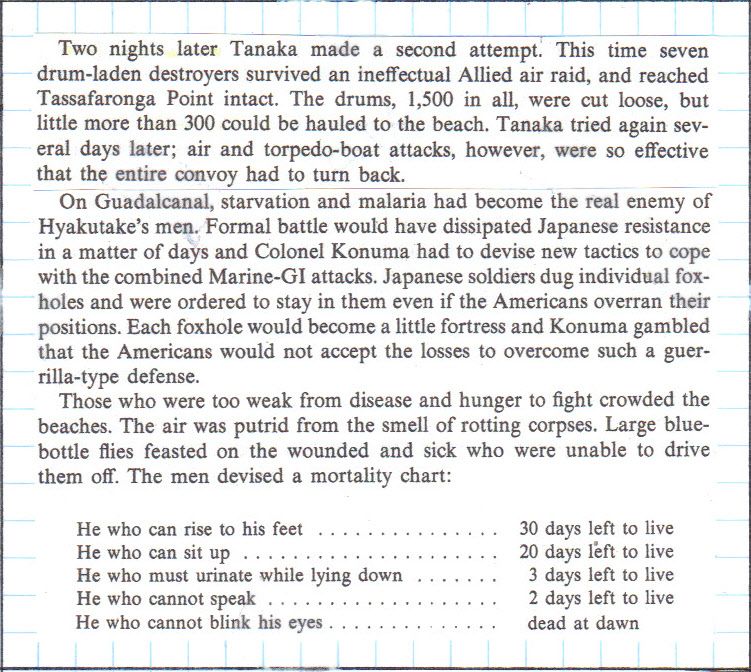

It’s interesting that the decisive land battles of each of the two theatres are both now being decided by starvation.

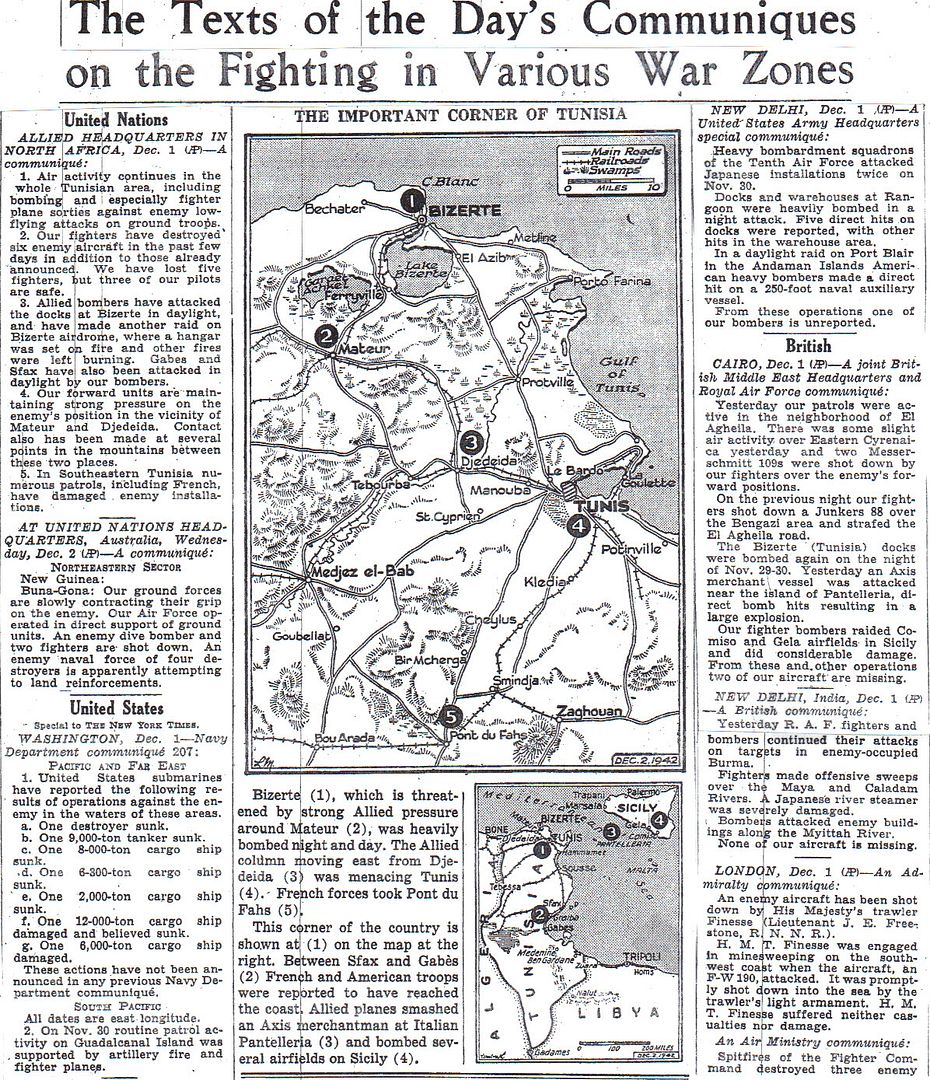

The reports from Tunisia are downright delusional about the imminent prospects for taking Tunis.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.