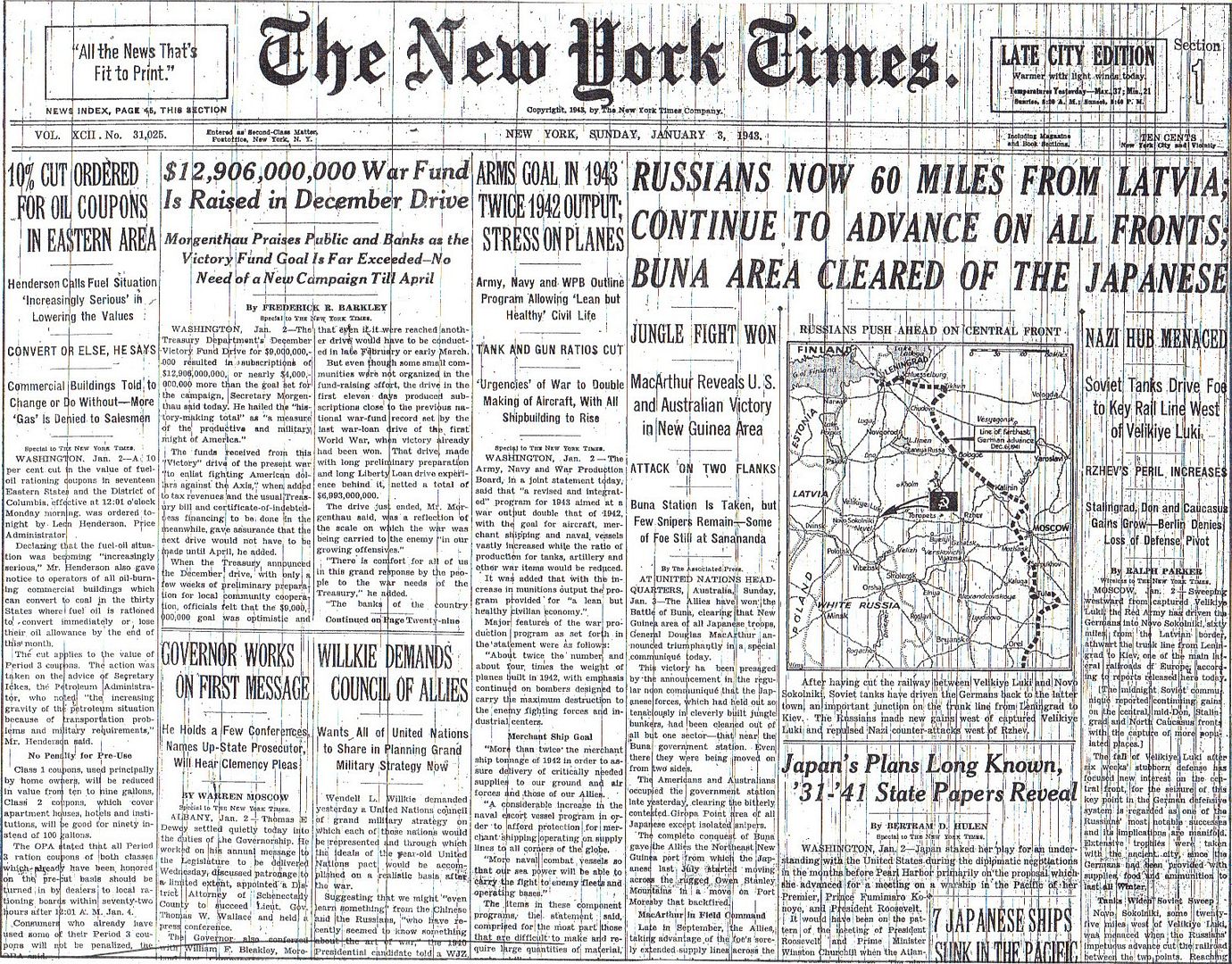

Posted on 01/03/2013 5:12:23 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

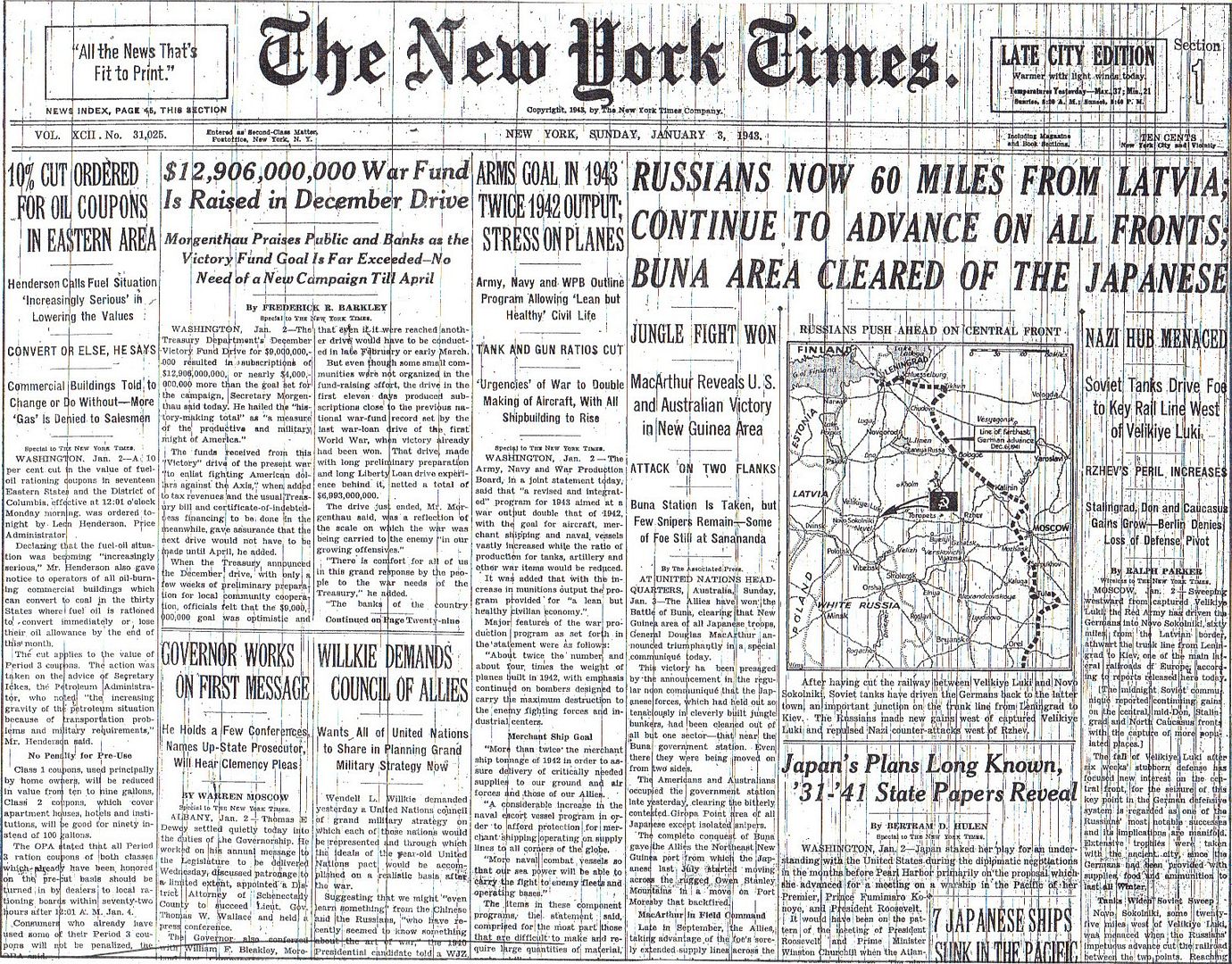

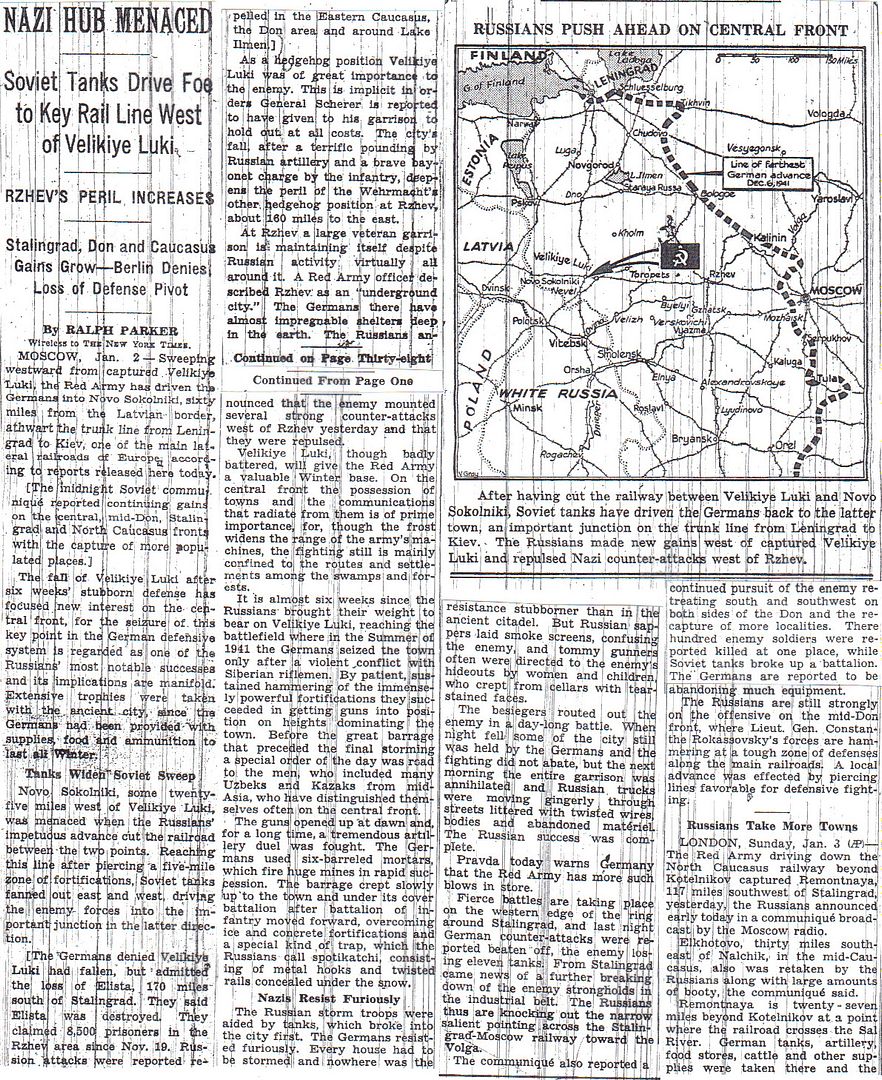

Nazi Hub Menaced (Parker) – 2-3

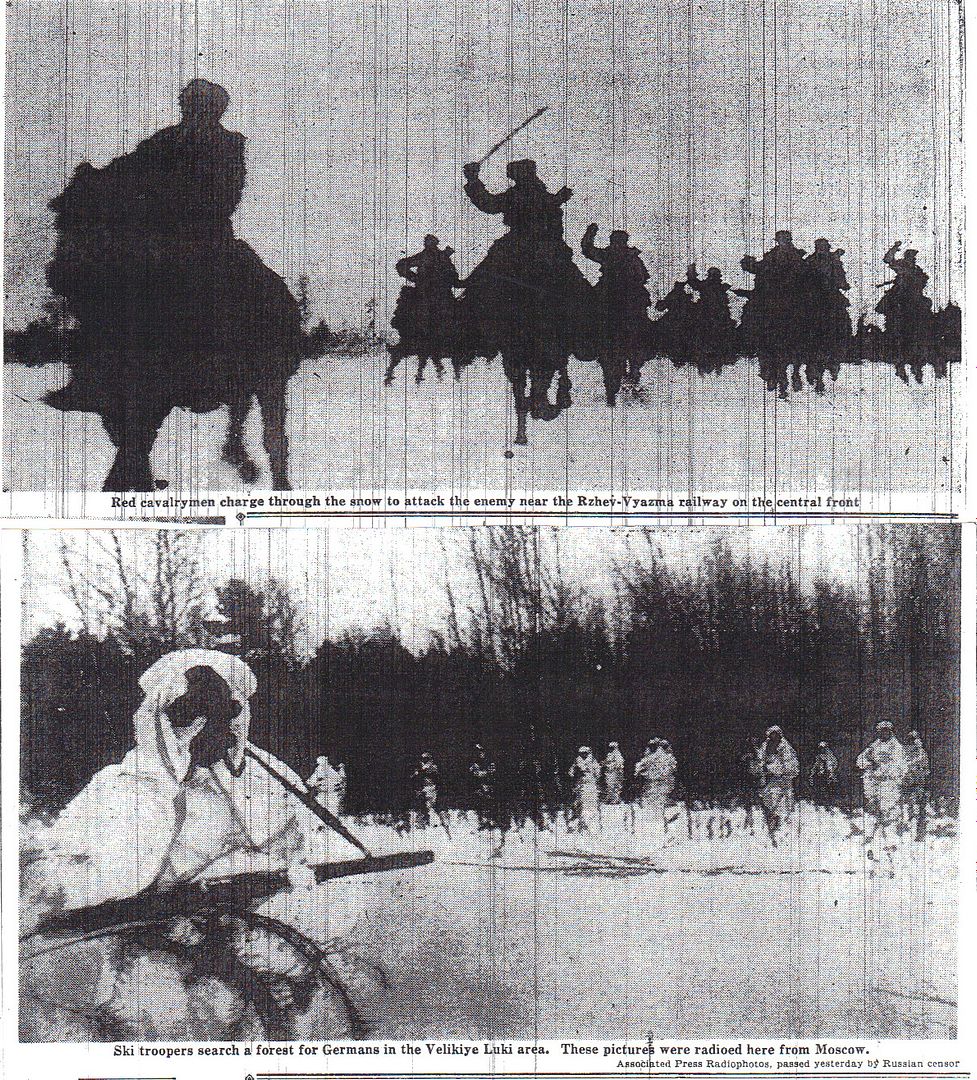

By Sled, Horse and Ski the Russians Harry the Nazi Troops Along the Winter Front (photos) – 3-4

Big Scale Battle Needed in Tunisia (Middleton) – 5

Germans Fortify Position in Libya (Sedgwick) – 5

Jungle Fight Won (Durdin) – 6

7 Japanese Ships Sunk in the Pacific – 7

War News Summarized – 7

Japan’s Plans Long Known, ’31-’41 State Papers Reveal (Hulen) – 8-9

Text of Hull’s Statement – 9

Halsey Predicts Victory This Year (by J. Norman Lodge, first-time contributor) – 10

The Texts of the Day’s Communiques on the War – 12-13

The News of the Week in Review

Twenty News Questions – 14

Editorials – 15-17

This Air-Land-Sea War

Death and Rebirth in France

“Psychological Disarmament”

For the Minds of Men

January

Dead, Wounded, Missing

Topics of the Times

Super-National Organization Held No Way to Peace (a letter to the editor by Ludwig von Mises) – 18-19

Golden Rule Tarnished (letter) – 20

To a Father (poetry) – 20

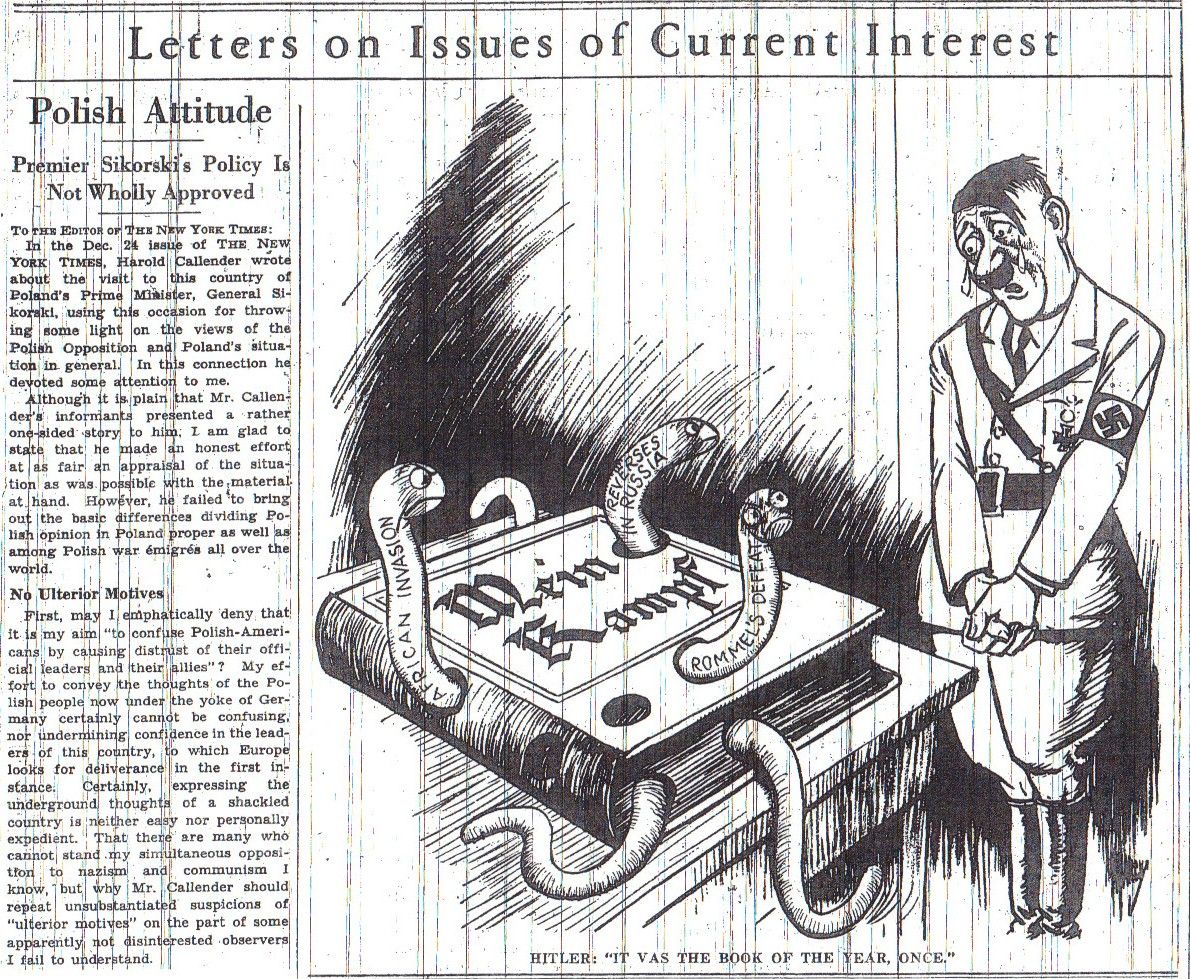

Letters on Issues of Current Interest – 21-23

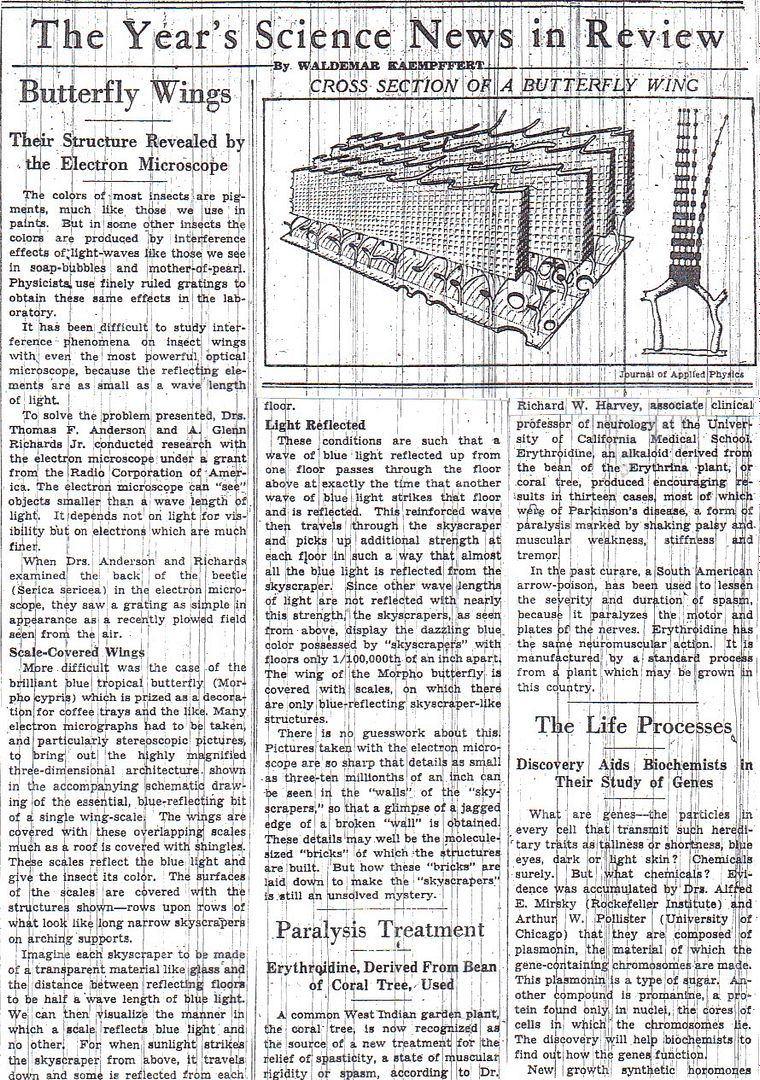

The Year’s Science News in Review – 24-25

Answers to Twenty News Questions - 26

http://www.onwar.com/chrono/1943/jan1943/f03jan43.htm

Luftwaffe Losses Mount Over Stalingrad

Sunday, January 3, 1943 www.onwar.com

Soviet forces retake Mozdok [photo at link]

On the Eastern Front... In the Caucasus, the Soviet offensive results in the capture of Mozdok and Malgobek by troops of the 58th and 44th Armies. In the Don basin, Army Group Don (Manstein) continues to resist Soviet attacks aimed at cutting off Army Group A (Kleist) in the Caucasus. The German 6th Army at Stalingrad continues to resist. The Luftwaffe is suffering substantial losses to its air transport fleet in the ongoing, though inadequate, attempt to supply the German army at Stalingrad.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/andrew.etherington/frame.htm

January 3rd, 1943

UNITED KINGDOM: A new Yugoslav Government is formed in London by former Prime Minister Yovanovitch. King Peter had been handed the resignation of the former government on 29 December 1942. (Jack McKillop)

Light cruiser HMS Uganda commissioned. (Dave Shirlaw)

FRANCE: The USAAF’s VIII Bomber Command flies Mission 28: The primary target is the St Nazaire U-Boat base, the first attack on this installation since 23 November 1942 and the heaviest attack to date against U-Boat bases to date. The command dispatches 85 B-17 Flying Fortresses and 13 B-24 Liberators; 60 B-17s and eight B-24s hit the target dropping 171 tons of bombs between 1130 and 1140 hours local. Formation (instead of individual) precision bombing is used for the first time by the VIII Bomber Command, and considerable damage is done to the dock area. Seven aircraft are lost (Jack McKillop)

During the day, RAF Bomber Command dispatches 11 (A-20) Bostons to Cherbourg but they are recalled. Three each Mosquitos attack railway targets in the Amiens and Tergnier areas. No aircraft are lost. (Jack McKillop)

During the night of 3/4 January, RAF Bomber Command dispatches 45 Wellingtons and Lancasters to lay mines off the Bay of Biscay coast: 15 off the Gironde Estuary; 7 off Lorient, six off St. Nazaire, three each off Amiens, Bayonne and Tergnier, and two each off La Pallice, Limoges and St. Jean de Luz. (Jack McKillop)

NETHERLANDS: During the night of 3/4 January, three RAF Bomber Command aircraft lay mines off Texel Island. (Jack McKillop)

GERMANY: During the night of 3/4 January, RAF Bomber Command dispatches three Pathfinder Mosquitos and 19 Lancasters to continue the Oboe-marking experimental raids on Essen. Three Lancasters are lost. (Jack McKillop)

U-310 launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

SICILY: British two-man “chariots” based on a modified torpedo, score their first combat success by sinking the Italian light cruiser ULPIO TRAIANO in Palermo harbour. The first such use of the device by the Royal Navy, which had copied it from the Italian Navy’s Maiale that had been used to considerable effect against British shipping earlier in the war.

GREECE: CRETE: RAF Baltimores operating under the USAAF IX Bomber Command, bomb Suda Bay and Timbakion Airfield on the southern coast. A few of the aircraft also bomb Kapistri in eastern Crete. (Jack McKillop)

U.S.S.R.: Exploiting the German withdrawal in the Caucasus, the Red Army occupies Mozdok and Malgobek.

TUNISIA: An Axis tank-infantry force, with artillery and air support, overruns the French 19th Corps troops at Fondouk. The British First Army’s V Corps, employing the 36th Brigade of the 78th Division, begins limited attacks to improve positions on Djebel Azag and Djebel Ajred, west of Mateur. The British 6th Armoured Division conducts a reconnaissance in force on the Goubellat plain. (Jack McKillop)

All USAAF XII Fighter Command units, i.e., fighters and light bombers (A-20 Havocs and DB-7 Bostons), attack Axis tanks at Fondouk el Aouareb. The fighters and light bombers attack the tanks as they move west from Fondouk; several tanks are reported destroyed or aflame and numerous other tanks and vehicles are damaged. (Jack McKillop)

U.S.S.R.: The Red Army recaptures Mozdok in the Caucasus.

NEW GUINEA: Japanese supplies and reinforcements are landed at Lae under Allied air attacks. This convoy will provide the Allied Air Force planners valuable experience for future use. Over 100 sorties are delivered by the USAAF Fifth Air Force. Lieutenant General George C. Kenny, Commanding General Allied Air Force and Commanding General USAAF Fifth Air Force, had information from ULTRA as to when the convoy would leave Rabaul, New Britain Island, Bismarck Archipelago, its destination and when it would arrive. Aircraft were ordered into the air as soon as they were ready. In some cases a medium or heavy bomber would attack singly, in other cases in twos or threes. Not surprisingly, with hindsight, the convoy handled them easily. One small transport is sunk by an Australian (PBY) Catalina attacking at night. After the convoy delivers its cargo, the Fifth Air Force sinks two more ships but by then the damage is done.

In Papua New Guinea, USAAF Fifth Air Force P-40s strafe troops in the waters off Buna as U.S. and Australian ground forces are mopping up in the nearby Buna Mission area. In Northeast New Guinea B-26 Marauders, along with a single B-24 Liberator, bomb Madang and A-20 Havocs hit Salamaua. (Jack McKillop)

103 sorties were delivered by 5th Air Force, but uncoordinated. Kenny had information from ULTRA as to when the convoy would leave Rabaul, its destination and when it would arrive. Aircraft were ordered into the air as soon as they were ready. In some cases a medium or heavy bomber would attack singly, in other cases in twos or threes. Not surprisingly, with hindsight, the convoy handled them easily.

Only one small transport was sunk, by an RAAF Catalina attacking at night. After the convoy delivered its cargo, 5th Air Force sank two more ships but by then the damage was done.

Mounting co-ordinated air attacks is harder than it looks. It requires a great deal of preparation and trained personnel on the ground at all airfields and at co-ordinating stations. At this stage, 5th AF didn’t have these.

After the debacle at Buna, the initiative lay firmly with the Japanese. Imamura had decided to withdraw his forces from the Buna enclave and at the same time reinforce Lae with fresh troops. For the moment the Hyakutake in the Solomons got nothing.

The troops landed at Lae were tasked with eliminating the last allied airhead north of the Owen Stanley ranges - Wau. No-one knows what Imamura intended. He paid lip-service to IGHQ’s orders to mount another attack on Port Moresby but I suspect he intended to draw MacArthur into another costly defensive battle, probably in the trackless coastal approaches to Salamaua (south of Lae). (Michael Alexander)

SOLOMON ISLANDS: The 6th US Marines land on Guadalcanal. The 1st Battalion, 132d Infantry Regiment, Americal Division, exerts pressure against the eastern part of the Gifu and establishes contact with 2d Battalion to the left.

BISMARCK ARCHIPELAGO: A lone USAAF Fifth Air Force B-24 Liberator strafes the airfield at Gasmata on New Britain Island. (Jack McKillop)

AUSTRALIA:

Minesweeper HMAS Bunbury commissioned.

U.S.A.: Destroyer escort USS Robert E Peary launched. (Dave Shirlaw)

A Prisoner of War camp is approved for location just outside Douglas, Wyoming. (Pat Holscher)

ATLANTIC OCEAN: U-337 (Type VIIC) is listed as missing today. There is no explanation for its loss. 47 dead (all hands lost). U-337 reported for the last time on 3 Jan, 1943 from position 63N, 12W. (Alex Gordon)

U-96 transferred an ill crewmember to U-163, which was on her way to base.

U-406 took on an ill crewmember from U-123.

At 1800, the unescorted SS Baron Dechmont was torpedoed and sunk by U-507 NW of Cape San Roque, Brazil. Seven crewmembers lost. The master was taken prisoner and later lost when the U-boat was sunk ten days later. 28 crewmembers and eight gunners landed at Fortaleza.

At 2252, SS British Vigilance (Master Evan Owen Evans) in convoy TM-1 was torpedoed by U-514 about 900 miles NE of Barbados in 20°58N/44°40W (grid DQ 9325) and abandoned. 25 crewmembers and two gunners were lost. The master, 21 crewmembers and five gunners were picked up by the HMS Saxifrage and landed at Gibraltar. (Dave Shirlaw)

"Rabbi Leo Baeck was one of the preeminent rabbis and theologians of German Jewry.

Ordained in 1897, Baeck served as a liberal rabbi in Berlin from 1912 until his deportation to the Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia, camp/ghetto in early 1943.

"When the Nazis created the Reich Representation of German Jews in 1933, Baeck was named its president.

As chief representative of German Jewry, he refused to leave Germany, even when his safety and that of German Jewry was threatened.

"After being deported to Theresienstadt, Baeck worked tirelessly to bolster the morale of many Jews, even those whom he knew were destined for Auschwitz.

After the war Baeck settled in London, where he became the president of the Council of Jews from Germany.

The Leo Baeck Institute, which is the primary research institution for the study of German Jewry, bears the name of this venerable man."

"Inside the Warsaw Ghetto, a worker drags an emaciated body from the street.

In January 1943 the Germans initiated a new deportation from the ghetto.

For the first time, Jews resisted with force, using their few weapons to fight the Germans on the streets and in the ghetto's buildings.

These skirmishes raised morale and provided vital experience for the decisive struggle that would begin a few months later."

"Ragged children wait in front of a brick wall in the Warsaw Ghetto.

By winter 1942-43, conditions within the ghetto were abominable.

Pipes froze and raw sewage spewed into the streets.

Typhus raged throughout the ghetto, and starvation rations were exacting a heavy toll on the Jewish populace.

Upwards of 5,000 people a month were dying, and those who clung to life were miserable beyond description."

"Prisoners held at Dachau work in a nearby armaments factory.

Perhaps a third of the slave laborers were Jewish; the remainder were political dissidents, clergymen, Gypsies, Jehovah's Witnesses, homosexuals, and Soviet POWs.

The exploitation of slave labor and the extension of the war effort fueled the camp's growth.

Dachau eventually included 36 subcamps that utilized 37,000 prisoners as forced laborers.

The vast majority of these workers were engaged in armaments production."

"Nazi propaganda recognized no boundaries when it rallied the German Volk behind the war effort.

In addition to the ever-present radio speeches and parades, postage stamps carried the message of military glory.

The battle scenes depicted in these stamps reinforced the link between the German nation and the war. "

THE time: Christmas 1942.

The headquarters of Field-Marshal von Manstein, C-in-C Army Group Don, was at Novocherkassk, twelve miles behind the Lower Don. The Marshal and his staff officers looked weary. They were all depressed by the fate of Sixth Army.

But behind their anxiety about the situation at Stalingrad there was an even graver one. The Soviet High Command was patently out to exploit the fortunes of war, or rather Hitler's mistakes in making Sixth Army rush ahead too far without adequate cover for its weak flanks, to achieve a far greater prize than the mere annihilation of one army.

Behind the operations of three Soviet army groups, which had been ceaselessly attacking between Volga and Don ever since 19th November 1942, which had encircled Stalingrad and torn open the Italian-Rumanian front for some sixty miles—behind that operation was more than just the liberation of Stalingrad and the encirclement of Paulus's Army. Behind it was a far greater, a breath-taking plan of the Soviet High Command.

Carefully prepared over a long time, dearly bought with great sacrifices, with lost armies, lost territory, and very nearly a lost war, the great counterblow was at last to be struck—here, from the Volga, from the womb of old Mother Russia, from Stalingrad, the holy place of the Bolshevik revolution. All past omissions were now to be redeemed, the great operation against Hitler was now to be mounted —the giant blow as against Napoleon, the annihilation of the Germans in the vast, open spaces of Russia. Stalin intended no more and no less than the shattering of the entire southern wing of the German armies in the East.

A super-Stalingrad for a million German troops—that was his objective.

By means of a gigantic operation of eight armies altogether, striking towards Rostov and the Lower Dnieper from the middle Don and the Kalmyk Steppe, he wanted to cut off and annihilate the entire German southern wing—three groups with altogether seven armies.

There is no parallel in military history for an operation plan of similar gigantic scale. Moreover, it seemed like success. Hour by hour more alarming reports arrived at Manstein's map table. How and with what was he to stem the Red flood? How was he to seal the huge gap between Don and Donets? The German High Command was facing a danger such as it had not faced before.

"Quiet," grunted the Soviet general. His reproachful glance fell on his orderly officer who was talking to a runner. Alarmed the major fell silent. The only sound now was the crackling of the fire in the stove of the peasant hut which served the Soviet XXIV Tank Corps as its command post during the night of 23rd-24th December 1942. The general was pressing a telephone to his ear. "Da—yes, yes." He chuckled. Then he gave his name again. "Everything according to plan," the general reported. "The Italians seem to have been blown away. They have no resistance left in the area behind their Eighth Army either. My formations are advancing unimpeded. We are already deep in the enemy hinterland and are covering some thirty miles a day. Our spearheads are at Tatsinskaya." Major- General V. M. Badanov, commanding the Soviet XXIV Tank Corps, was clearly proud of the telephone report he was making to the C-in-C of the First Guards Army. And General Kuznetsov sounded pleased too: "Excellent, Comrade Badanov. I shall report your successes to headquarters. But keep moving, always keep moving—this is our moment!"

It was indeed Badanov's moment. His XXIV Tank Corps, assigned to First Guards Army, was racing far ahead of the Soviet offensive wedges which were advancing through the shattered front of the Italian Eighth Army, on towards the Donets. Badanov encountered hardly any appreciable opposition. Blocking units employed in the depth of the Italian front, in the catchment area of the Chir, soon scattered under the impact of the Soviet attacks. Guns and motor vehicles were abandoned. Many officers removed their badges of rank and tried to make good their escape. So why should the other ranks be more heroic? They threw their weapons away and fled also.

All Badanov's corps had to do was to keep moving. By the evening of 23rd December 1942 their spearheads had reached Tatsinskaya, the important forward airfield and supply centre for Stalingrad, 150 miles behind the shattered Italian front. The corps had covered this distance in five days—blitzkrieg in the best German tradition! A distance of 150 miles in five days—that was nearly the distance and the speed of Manstein's famous Panzer raid to Dvinsk in the first week of the war. Then, eighteen months earlier, his LVI Panzer Corps had covered the distance from the area east of Tilsit to Dvinsk, a distance of 170 miles, in four days. The Russians had learnt a lot since then.

As General Badanov replaced the receiver of his field telephone he turned to his chief of staff: "What d'you think, Comrade Colonel, do we attack the German base and the airfield tonight or do we wait till tomorrow?"

The Colonel slowly shook his head. "Tomorrow the Germans celebrate Christmas—that's the most sentimental of their feasts. They make up little presents, they stick candles on fir trees and prepare for their Holy Night. That'll make them careless. We might take them by surprise."

Badanov nodded. Then he made out his orders for his unit commanders. The plan succeeded.

In thick fog during the small hours of 24th December Badanov's tanks moved off. They rolled straight down the runways of the airfield of Tatsinskaya.

Of course, VIII Air Corps realized the threatening danger, but Fourth Air Fleet was not allowed to order the evacuation of the important supply base and its huge stores. Orders said: Hold on. But how was one to hold on, far behind the main German defensive line on the Chir, when faced with a Soviet armored corps? A mere 120 men, one 8.8-cm gun and six 2-cm flak guns—that was all the Germans had to oppose the Soviets with at Tatsinskaya.

General Badanov records in his memoirs that the Soviet armored spearheads found the German gun positions and strongpoints unmanned. The aircrews too were in their bunkers. "Everybody was sleeping peacefully," the general records. According to his account the signal for the attack was given by a mortar battery. A few hours later the vital supply base for the encircled city of Stalingrad fell to the Russians without appreciable resistance. Badanov states that 350 aircraft and enormous quantities of materiel, food supplies, and ammunition, including complete train transports, were captured.

The poor defense of the important base of Tatsinskaya was certainly a serious blunder. But one thing is certain: Badanov's figure of captured aircraft cannot be correct.

Only 180 machines were on the field. Most of these took off under enemy fire, in spite of the fog. And 124 arrived safely at other airfields.

Nevertheless it was a terrible blow. Tatsinskaya was not only the supply centre for Stalingrad but also a communications centre—the railhead of the important lines from Rostov and the Donets area. The development was particularly serious for Army Detachment Hollidt. This formation was still a long way to the east of Tatsinskaya, on the Chir, and now found itself threatened from its rear. Once more the price had to be paid for Hitler's disastrous strategy of holding an at all costs. Nothing was ever to be surrendered. Hold on, hold on, hold on—whatever the price.

Admittedly, the position held by Hollidt on the Chir was of very considerable importance. It was from there that XLVIII Panzer Corps was to support Hoth's relief attack towards Stalingrad. For that reason, favorable salients in the front line seemed useful to OKH. But wish and reality were incompatible. The danger grew from day to day, and the prospect of success became less. Hitler, however, refused to see the danger. When Manstein asked for reinforcements Hitler's reply was: "I haven't got any." When he proposed strategically unavoidable withdrawals, Hitler lamented: "Without the Caucasian oil and the mineral wealth of the Donets area the war can no longer be won."

Manstein was in a difficult position. He had to battle not only against the Russians but also against the Führer's headquarters. Any other man would have caved in. But Manstein found a way. He resorted to an ingenious system of strategic make-shift arrangements. In this he had the help of three experienced commanders in the field, men on whom he could rely—Colonel-General Hoth, whose Fourth Panzer Army was still fighting south-east of the Don; General Hollidt, whose mixed Army Detachment in the big Don bend was holding the main defensive line of the Gnilaya and the Chir; General Fretter-Pico, whose newly organized Army Detachment was trying to set up a blocking position in the area between Millerovo and the Kalitva river.

The main danger now was Badanov, the spearheads of the Soviet First Guards Army. For it was a mere eighty miles from Tatsinskaya to Rostov. Manstein knew that, in the present conditions, a fearless tank commander could cover the distance in three days. And Badanov certainly was fearless. If he struck at Rostov things would be really critical. If the Soviets succeeded in slamming the only door, the only overland link with the armies of Army Group A in the Caucasus, then 800,000 men would be trapped. And Fourth Panzer Army as well. Field-Marshal Manstein realized this. And General Badanov realized it too.

The Field-Marshal sat at Novocherkassk and together with his chief of staff, Major-General Schulz, and his chief of operations, Colonel Busse, coolly evaluated the situation. This was the moment for bold, daring, but also fateful decisions. It was one of those moments when a general must decide how much he can expect from his officers and men. Manstein knew the capacity of his formations but he also knew the limits to which they could be stretched. That too was part of his genius as a general.

Manstein asked Hoth, whose army on the southern front of Army Group Don was still engaged in the relief attack towards Stalingrad, to let him have one division in order to save Tatsinskaya. On his own responsibility, because he realized the disastrous situation, Hoth transferred to him his most powerful Panzer Division, the 6th Panzer Division under General Raus. Colonel von Hünersdorff, Manstein's chief of staff during the offensive operations of the previous year, now commanded the Paderborn 11th Panzer Regiment in that division.

In an icy night march the division was transferred to the north, to Army Detachment Hollidt, where Colonel Wenck, its indefatigable chief of staff and a brilliant improviser, had built up a first weak line of defense from a motley array of formations.

It was a difficult and a fateful decision which Manstein and Hoth had taken upon themselves. For with the loss of his 6th Panzer Division Hoth also lost his last feeble hope of being able to hold on in his hard-pressed position thirty miles from Stalingrad, and thus of ever being able to resume the relief attack. But then this relief attack, though begun with such high hopes, had in any case virtually failed. Even without a successful blow against Badanov, Hoth's situation would soon have become untenable because he too would be threatened with encirclement. The only choice he had was between a greater and a lesser disaster.

And the greater disaster could be averted—if at all—only by means of Manstein's plan. And this plan was based on the following considerations. The only real armored formation which Hollidt still possessed on the Chir was General Balck's well-tried Silesian 11th Panzer Division. It had been engaged in skirmishes with penetrating enemy tanks on the left wing of Hoth's group ever since mid-December. Colonel Count Schimmelmann commanded its 15th Panzer Regiment. True, he only had twenty-five armored fighting vehicles left, but General Balck had nevertheless been able, with this force of tanks, reinforced by Panzer grenadiers, engineers, and flak, and with 336th Infantry Division under General Lucht, to annihilate two strong enemy striking forces in a kind of running battle and in knocking out sixty-five tanks without losing a single one himself.

The outstanding part played in this fighting by the infantry is also shown by the fact that 336th Infantry Division knocked out ninety-two enemy tanks in five days.

This success enabled Manstein to move 11th Panzer Division against Badanov's corps after a tiring night march on 23rd December in a temperature of minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Jointly with 6th Panzer Division, which was coming up in forced marches, it was to halt General Badanov's daring and dangerous raid.

In the flat, snow-covered steppe between Kalitva and Chir the German Panzer regiments again demonstrated the meaning of modern tank tactics. While the Grenadier battalions of 306th Infantry Division sealed off the important supply centre from the east and then sent in assault parties of 579th Grenadier Regiment to recapture parts of the airfield, the German counter-attacks were mounted. As early as 24th December an armored advanced detachment of 6th Panzer Division, supported by assault guns, captured the area north of Tatsinskaya. By 27th December General Balck's formations had laid an iron ring around the Russian corps at Tatsinskaya. The 6th Panzer Division now blocked the retreat of the Soviet formations, cut them off from their supplies, and screened off the front along the Bystraya against any attempts from the north for their relief.

Then began the battle for Tatsinskaya.

Badanov's armor was trapped. The corps had been taken by surprise. Badanov sent one SOS after another to his Army Group. General Vatutin replied with reassuring signals. He urged him to hold on. He employed what forces he had—two motorized corps and two rifle divisions—to relieve Badanov. He was determined to save Badanov and get his corps moving again. Too much was at stake for the Soviet Command: they wanted to get to Rostov. But the Russians too were at the end of their strength that winter.

General Raus with his 6th Panzer Division resisted all attacks. And Balck's 11th Panzer Division, together with 4th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, commanded by the fearless Colonel Unrein, and with the grenadiers of 306th Infantry Division, turned the battle into a costly defeat for Badanov's regiments at Tatsinskaya. The Soviet XXIV Tank Corps was wiped out in heavy night fighting in a cutting cold. Badanov's units resisted desperately. Many groups fought to their last round. The burning grain silos and storage depots of Tatsinskaya lit up a ghostly battle scene—rammed tanks, crushed anti-tank guns, overturned supply columns, wounded men frozen to death. By 28th December it was all over. Isolated Soviet troops broke through the German encirclement in the north of the town and made good their escape across the Bystraya stream. Badanov's corps, which so hopefully launched its offensive towards Rostov just before Christmas, had ceased to exist.

The Soviet High Command and the Supreme Soviet bestowed on Badanov's regiments the halo of heroes. Their gallant stand to the last, and above all their unparalleled armored raid deep into the rear of the German lines were to be a shining example to the rest of the Red Army. The newly raised corps was therefore granted the title of "II Tatsinskaya Tank Corps". And Badanov himself was the first officer of the Red Army to be decorated with the Order of Suvorov.

German blitzkrieg methods with large armored formations had clearly become the model for Soviet operations. For the moment, however, these new tactics did not bring them success. The German tank commanders were still superior in skill. This was again demonstrated four days later. Late on New Year's Eve, just before the beginning of 1943, the Soviet XXV Tank Corps ran into a trap in an attempt to imitate Badanov's method. An error and recklessness led it into disaster.

Misled by the very slight resistance they had encountered when breaking through the southern wing of the Italian Eighth Army, the Corps omitted to send reconnaissance units out. It was thought that there was no serious adversary left. The Russian armored brigades emerged from their patches of woodland north of the Bystraya stream with their headlights full on and made for the ford near Maryevka. They intended to cross the river in a southerly direction in order to strike at the rear of the German Army Detachment Hollidt.

But the battle outposts of 6th Panzer Division on the Bystraya noticed the Soviet advance towards the ford. General Raus swiftly made his plan for a night engagement. He ordered his 7.5-cm antitank troops forward in order to delay the Soviet tanks. The 11th panzer Regiment was alerted and kept in readiness. The bulk of the Soviet XXV Corps was allowed to cross the ford into Maryevka with most of its tanks. Then the crossing point was sealed off with the anti-tank troops held in readiness and with heavy armored scout cars. And now General Raus opened the nocturnal tank battle between Maryevka and Romanov. The enemy, held up frontally, was attacked from both flanks and in the rear. The Russians were taken by surprise and reacted confusedly and nervously. Raus, on the other hand, calmly conducted the battle like a game of chess. Blazing T-34s lit up the scene. Using separate packs of tanks, the Soviets again and again tried to force a breach. Who was a friend and who an enemy? This question could be answered only at closest range. Furiously the Soviet tank commanders tried to exploit the robust construction of their T-34s and to eliminate the German Panzers by ramming them. But the mobility of the Panzer IV and the experience of the German tank commanders paid off—especially in the breakthrough attempt of a Soviet armored group at Novomaryevka, where Major Dr Bäke held a covering position with his 2nd Battalion, 11th Panzer Regiment.

Bäke had ten Panzer IVs available, and only a handful of infantrymen. Soviet T-34s attacked towards 3AM and broke into the village.

Battles of tank against tank developed between the houses. The straw-thatched huts were soon ablaze. The flickering flames produced bizarre shadows. Standing about in the village were a few damaged, unmanned German tanks, awaiting repair. These provided an unexpected support for Bäke's small fighting force. In the uncertain light of the blazing 'village the Russians regarded the wrecks as intact tanks and time and again concentrated their fire on these tempting stationary targets. This gave Bäke's tanks the time and opportunity to move into good firing positions themselves. Eventually he withdrew his little armada from among the damaged tanks and houses of the village. In the course of this disengagement Bäke's command tank—which, like all other command tanks, merely carried a wooden dummy gun because of the space inside being needed for the bulky radio equipment and the map table— happened to cross the bow of a T-34. The Russian immediately traversed his gun to open fire. "Ram him!" Bäke ordered. But the maneuver would hardly have saved him. Salvation came from the tank of the commander of 7th Company, Captain Gericke. His Panzer IV was lying in ambush at a street corner, its gun ready for action. He saw the Russian tank just in time: "Fire!" It was a direct hit. When he rallied outside the village, Bäke found that he was left with six tanks and twenty-five men. Once it got light and the Russians realized their superiority things might look ugly. For that reason the night had to be exploited for the counter-attack. At night deception was possible. Night favored the weaker side. Under cover of darkness one might, by means of lights and noise, make six tanks look like a whole battalion.

Major Bäke posted his six tanks all round the village. On the prearranged flare signal they all attacked. The twenty-five infantrymen, strung out between the tanks, yelled "Hurra" as loud as they could and fired as many rounds as possible from their small arms. The tanks also made as much noise as possible and fired tracer ammunition. The bluff succeeded.

Bäke quickly reached the centre of the village. The Russians, suspecting a large-scale attack, fell back towards the Bystraya. But there they were caught by the German anti-tank guns which were waiting for them. The Russians had crossed the Bystraya with ninety tanks. When day broke, ninety wrecked T-34s littered the wintery battlefield. Thus XXV Tank Corps, the second offensive wedge of the Soviet Guards Army, was wiped out.

The losses of 6th Panzer Division amounted to twenty-three armored fighting vehicles. And since it remained in possession of the battlefield, most of these were made battle-worthy again by the workshop companies. With the smashing of the two Soviet armored groups on the northern front of Army Group Don the immediate danger threatening Rostov from the north-east was averted. The equally dangerous Soviet thrust by the Soviet Sixth and First Guards Armies from the northern edge of the breach in the direction of the Donets via Millerovo was successfully halted by the weak formations of Army Detachment Fretter-Pico.

Army Detachment was rather a grand name for the forces available to General Fretter-Pico for sealing a gap of nearly 120 miles. At Millerovo parts of 3rd Mountain Division resolutely and successfully resisted superior enemy armored forces. Field-training regiments and draft-conducting battalions, together with von der Lancken's battered Panzer group, had to face the assault of enemy armored divisions.

Eventually the 304th Infantry Division was transferred to Russia from France. From coastal-defense duties along the peaceful Atlantic Wall. Its regiments, after a mere twelve hours' fighting on the Eastern Front, found themselves at breaking point.

The fact that Fretter-Pico and the division's experienced commander, Major-General Sieler, nevertheless succeeded in nursing the riflemen and gunners through the initial shock of being faced with powerful enemy armor and in turning them, within a few weeks, into tough fighters, was an amazing achievement. Luckily, Fretter-Pico had two experienced and battle-tested Panzer Divisions at his disposal—the Thuringian 7th and the Lower Saxon 19th, whose indefatigable counter-attacks made the defensive fighting easier for the infantry and also protected the northern flank of the threatened front. Thus the Army Detachment Fretter-Pico, though in fact a weak corps, became a successful breakwater between Don and Donets and by its elastic method of operation prevented a strategic breakthrough by an enemy more than twenty times its numerical superior. Fretter-Pico rightly observed: "It was a victory for the infantryman's fighting morale." The successful German defensive operations between Don and Donets held the door open for the German armies still in the Caucasus against the northern jaw of the Soviet pincers. But the absence of the forces employed to avert this danger was now acutely felt by Manstein on the right wing of his front, at Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army, between Don and Manych. And now disaster threatened there.

Every morning at daybreak during those last few days of December, Colonel-General Hoth set out in his armored command car on a tour of his shrunken divisions and visited their commanders at their headquarters. Many a regiment was reduced to the strength of a weak battalion. Battalions were down to company strength. Fourth Panzer Army was left with a mere fifty to seventy battle-worthy tanks, normally the equipment of a single weak battalion. At nightfall the tough and energetic army commander returned to his headquarters, completely exhausted. Colonel Fangohr, his chief of staff, was waiting for him with the situation map, the signals from Manstein, and the log of telephone conversations. It was a hopeless struggle. Fourth Panzer Army was spending itself in costly defensive fighting.

In the evenings there was only one subject: How, having given away its 6th Panzer Division, could the army hold the front with the small forces it had left?

Hitler persisted in refusing to release 16th Panzer Grenadier Division which was still holding positions deep in the Kalmyk Steppes at Elista. The 5th (Viking) SS Panzer Grenadier Division, promised by Army Group A from the Caucasus, was still somewhere in transit.

Day after day Fangohr reported how he had been on to Army Group. And day after day he received the same reply from Manstein's chief of operations, Colonel Busse: We keep asking Hitler to release First Panzer Army and put it under our command—but in vain. OKH cannot make up its mind about anything. Step by step, Hoth moved his troops back from switchline to switch-line, towards the south-west. From the Myshkova sector to the Aksay. From the Aksay to the Sal to the Kuberle. By sudden sharp counter-attacks he kept harassing the enemy who was pressing hard on his heels. Toughness, ingenuity, fresh ideas, indefatigable drive, and fearlessness —these were the qualities which enabled the colonel-general to stand up with his weakened LVII Panzer Corps to a superior Soviet force of three armies. And all the time he was conscious of his responsibility for the further course of the fighting—he must prevent a Russian advance to Rostov from the east and south-east, just as Hollidt and Fretter- Pico had averted it from the north, and he must cover the rear of the German armies still in the Caucasus. At long last, at the end of December, Hitler authorized the evacuation of the Caucasus. But the rearguards of First Panzer Army were still on the Terek, 400 miles from Rostov.

The situation map of the southern front of the German armies in the East looked terrible. Everywhere there were red arrows, indicating Soviet thrusts, and the thin blue lines of the German positions were submerged in this red sea. There was no longer any secure contact between Hollidt's and Hoth's formations, since, about mid-January, Fourth Panzer Army had been forced towards the south-east, behind the Manych. Between Don and Sal was a new, dangerous gap of twenty-five miles. Into that gap two Soviet armies of Yeremenko's Army Group were now advancing—the Second Guards Army and the Fifty-First Army. They kept moving forward. They covered their flanks to right and left, but the bulk of both armies was inexorably moving towards Rostov. Its movements, entered on the situation map, looked like a huge, nine-headed hydra—a hydra whose tentacles were threatening both Hoth and Hollidt. But the first part of this advancing hydra had already reached the Don to the north-east of Rostov. This was the Soviet III Guards Tank Corps under General Rotmistrov, the crack formation which earned its Guards title in the fighting for Stalingrad.

A chill ran down the spines of the staff officers of the German Army Group Don at Novocherkassk whenever they glanced at their situation map. The world's eyes were still riveted on Stalingrad, but down here, at Rostov, at the bridges of Bataysk, the real decisions were being made. Here a disaster was threatening which was three times the magnitude of Stalingrad. Could the race against time and against the Soviets be won? Would Field-Marshal von Kleist's Army Group A get to Rostov in time to slip through the narrow door?

On 7th January 1943, an icy-cold Thursday, Captain Annius, the orderly officer, burst into Manstein's room: "Herr Feldmarschall, Soviet tanks have crossed the Don only twelve miles from here and are making straight for us. They are evidently trying to mop us up. Our Cossack covering parties have been overrun. We've nothing left."

[Cossack units from the Russian and Ukrainian steppes, as well as units of Caucasian and other non-Russian tribes in the German-held parts of the U.S.S.R., had either defected to the Germans or been raised by them from the civilian population. They were traditionally anti-Russian rather than specifically anti-Soviet, and served as "auxiliary units", usually mounted, on the German side. After the war Stalin took savage reprisals against some of these tribes, often deporting the entire population to Siberia and abolishing such limited local autonomy as they had enjoyed. After Stalin's death and Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin's crimes some of the tribes were brought back from east of the Urals and allowed to resettle in their old homes. (Translator's note.)] Manstein calmly regarded his orderly officer. All he said was: "That so?"

It was one of those moments when the Field-Marshal showed that he was not only a strategist of genius but also a man of imperturbable temperament. He hated alarms and excitement.

"We've got all sorts of things left, Annius," he said to the captain with a smile. "Scrape together whatever you can find. That tank repair shop next door—surely there are bound to be a few more or less operational tanks there. Collect whatever can be used, and go and knock out the Soviets. Get the staff organized for defense. We're staying put. I'll leave you to cope with this little disturbance!" Annius, staggered by the Field-Marshal's stolid calm, rushed out. The tank repair shop! Why didn't he think of it himself?

Half an hour later the captain led a small, motley handful of armor from Novocherkassk against the Don, intercepted the forward Soviet reconnaissance units, and threw the enemy armored spearheads back across the river. The day was vibrant with excitement and with frost. This episode is typical of the drama of the situation. One Soviet tank regiment with a go-getting commander might well have decided the war at this point. For the capture of Rostov would have decided the war; it would have meant the undoubted encirclement of three or four German armies with roughly a million men.

Why did Yeremenko, the Soviet Supreme Commander of the Southern Front, not assign this task to such a go-getter?

Did he overrate the German defensive forces? Or had the example of Badanov's XXIV Tank Corps had a sobering effect?

With a dark scowl General Malinovskiy listened to the reports about the unsuccessful Soviet armored thrust against Novocherkassk. Even the best troops can't do the impossible," his chief of staff said apologetically. The general nodded. He did not need to be told. As the experienced commander-in-chief of the Second Guards Army, Malinovskiy knew that even a crack formation such as his III Guards Tank Corps was now exhausted. It was dangling at the end of an extremely tenuous supply thread. Its fighting power was melting away, that once so dramatic fighting power with which General Rotmistrov had stopped the German relief attack towards Stalingrad. Malinovskiy was aware of all that and so was Yeremenko, the C-in-C of Army Group Southern Front. Even Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, the powerful Military Council member for the Army Group, realized the difficulties. But Moscow headquarters refused to see them. Khrushchev and Yeremenko had to justify the orders of headquarters. And these orders were now on Malinovskiy's map table: "Second Guards Army will reach the Donets by the evening of 7th January. The III Guards Tank Corps will cross over to the western bank of the Don and take firm possession of the river crossings. The 98th Rifle Division will widen the penetration. The II Guards Mechanized Corps will.... The V Guards Mechanized Corps will…. "Will, will, will!" Malinovskiy exploded, his hand slamming down on the map table at each word. "And what about the Germans who are still there? Not Rumanians or Italians, but Germans! That's something ; headquarters seem to have forgotten!"

But what was the use of arguing? "Bataysk must fall—Rostov must be taken!" These were the daily orders from Khrushchev and Yeremenko. Orders in writing. Orders by telephone. Verbal orders. Urgent directives. The armies passed on the orders to the corps. And the corps passed them on to the regiments. And the regiments to the battalions. But orders were not yet battles won. Progress was slow. Much too slow. Not until 20th January did the spearheads of Yeremenko's slowly advancing forces cross the Manych at Manychskaya and thrust towards the west in the direction of Bataysk. Colonel Yegorov commanded the advanced detachment. Eight T-34s, three T-70s, nine armored infantry carriers, five armored scout cars and 200 infantry riding on the vehicles were charging towards the great objective—the objective they hoped to take by a surprise coup. The bulk of III Guards Tank Corps was waiting for its cue to follow up. Everything had been carefully planned. Farther south, Fifty-First Army moved its III Guards Mechanized Corps towards Bataysk with a strong armored combat group. The door was to be slammed shut. Already the railway line to Rostov had been cut and the Lenin collective farm reached.

In the Manychskaya bridgehead Malinovskiy was standing ready to follow up with two corps. The danger threatening the southern wing of the German Eastern Front was tremendous. Three German armies were in danger of being cut off. The gap was now only nineteen miles wide.

A mere nineteen miles stood between roughly 900,000 German troops and the fate of Stalingrad.

Nineteen miles no distance at all. It was one of those rare moments when history was visibly and breath-takingly concentrated within a few square miles, waiting to be given a crucial push one way or another. "How can we push in this dangerous bridgehead of Manychskaya?" Field-Marshal von Manstein asked his chief of operations, Colonel Theodor Busse. "Hoth can't possibly do it on his own," Busse replied. "No, he obviously can't. But what have we left?"

Manstein stepped up to the map. It showed clearly what had happened during the past week. The Field-Marshal had at last wrung from Hitler permission for the Army Detachments Hollidt and Fretter-Pico to fall back to the Donets. This now made it possible for forces to be pulled out to support Hoth and to defend Rostov. "We'll take Balck's 11th Panzer Division from Hollidt, pull it through Rostov to the southern bank of the Don, and give it to Hoth for his counter-attack against Malinovskiy's bridgehead," Manstein was thinking aloud. "But the 11th on its own won't be a match for the strong Russian armored corps at Manychskaya," Busse objected. Manstein nodded. "But Hoth still has the intact 16th Motorized Infantry Division which managed to disengage itself from Elista. Count Schwerin successfully piloted it through the Soviet Twenty-Eighth Army. With its Panzer Battalion 116 and a company of Tiger Battalion 503 it is just what's needed to strike against Manychskaya."

Manstein was referring to the superb achievements of Count Schwerin's 16th Panzer Grenadier Division during the past few weeks. Everyone still called it the 16th Motorized Infantry Division, for it was under that name that it had gained fame originally. The "Greyhound Division" had accomplished one of the most unusual, the most adventurous, and downright fantastic tasks of the whole Russian campaign—it had formed the easternmost outpost of the German armed forces in the Kalmyk Steppe and had secured the area around Elista as far as the Caspian Sea and the southern estuary of the Volga. Long-range reconnaissance parties of its Motorcycle Battalion 165 had got within sight of the Caspian, blown up oil trains from Baku, and by a ruse even telephoned the station-master of Astrakhan.

For months the division had covered the 200-mile gap between First Panzer Army and Fourth Panzer Army against the Soviet Twenty-Eighth Army, thus protecting the two Panzer armies against being encircled from the Kalmyk Steppe. All alone in the boundless steppe, reduced entirely to their own devices, the men from the Rhineland, Westphalia, and Thuringia discharged their task brilliantly. When the overall situation called for it, Count Schwerin, against Hitler's orders to the contrary, withdrew his formations at the right moment and established new switchlines along the Manych. Eventually, in mid-January 1943, the 16th Motorized Infantry Division foiled a particularly dangerous operation of the Soviets between Manych and Don. At that moment General Kirchner's LVII Panzer Corps had fallen back to the Manych in furious fighting. There, Hoth's Panzer Army was desperately trying to hold the Manych line. To hold that line was vital if the Don crossing near Rostov and Bataysk was to be kept open. Until 12th January Kirchner was able to hold a bridgehead over the Manych east of Proletarskaya with 23rd Panzer Division, 5th (Viking) SS Panzer Grenadier Division, and 17th Panzer Division, as well as the Tiger Battalion 503. Then the 16th Motorized Infantry Division was overtaken by fast Soviet formations. Strong units of armor and infantry of the Soviet Twenty-Eighth Army were thrusting towards Proletarskaya in order to force a crossing of the Manych there. Simultaneously a mechanized corps of Fifty-First Army attacked between Proletarskaya and Salsk. And a further corps of the Second Guards Army was wheeling towards Spornyy from the north. From there it was to move on towards Tikhoretsk in order to link up with units of the Soviet Transcaucasian Front. The objective of this boldly conceived Soviet operation was to split up the German Army Group A, to prevent First Panzer Army from getting to Rostov, and at the same time to cut off and surround the Seventeenth Army. It was an exceedingly dangerous operation at the worst possible moment: the retreating transport columns of First Panzer Army were jammed up at Bataysk. Numerous hospital trains and supply columns were bogged down outside the town. The few poor roads from south to north were clogged for miles on end. A Russian thrust into these immobilized columns would have meant chaos.

Frederick the Great once said: "A general must not only have courage; he must also have la fortune." Major-General Gerhard Count Schwerin had a lot of courage and he also had la fortune. Two days before the Russian thrust at Manych from the north, Captain Tebbe's Panzer Battalion 116 captured a Soviet General Staff officer in the course of a counter-attack. The officer's dispatch case contained maps and orders. They were the Soviet plans and directives for their operation against Spornyy. Count Schwerin did not hesitate. With all the forces at his disposal he chased towards Spornyy.

The Russians had already crossed the dam as well as a temporary bridge which had been built over the damaged parts, and were now moving fast towards the west, towards the retreat roads of First Panzer Army. Their objective was Bataysk. It was a well thought-out plan. But General Gerasimenko, the C-in-C of the Soviet Twenty-Eighth Army, had made his calculations without Schwerin. The morning of 15th January was clear and frosty. Captain Gerhard Tebbe's Panzer companies, with riflemen of the Münster 60th Motorized Infantry Regiment riding on the tanks, were moving against the Russian strongpoints from the north-east. They took no notice of what was happening on their right or left. They just drove on. They radioed signals. They fired their guns. They punched their way through. They seized the high ground in the rear of the Russians who had already crossed the river. They about-turned and with three assault parties attacked the enemy-held village.

A T-34 and four 7.62-cm anti-tank guns, positioned to cover the village, were knocked out. Two T-34s came to their aid. One of them was hit at once, the other turned back. On the left wing of the armored combat group was a troop of Lieutenant Kühne's 3rd Company. The troop commander was Sergeant Hans Bunzel, a Thuringian with quite a reputation for dealing with bridges and fortified hills. He was one of those resilient and resourceful men who are the backbone of any tank regiment. He demonstrated this again on 15th January 1943. His tanks pushed as far as the Spornyy dam over the Manych. Bunzel in his Panzer III was driving furiously towards the bridge. His 5-cm tank cannon was pounding the Soviet anti- tank guns covering the bridge. The sergeant was thinking back to that July day in 1942, when, with four tanks of his troop, he had tried to take the Manych dam, the frontier between Europe and Asia, at that very spot—only in the opposite direction. But on that occasion the dam was blown up right in front of his eyes.

Would he succeed this time? Yes—this time he was luckier. All went well. On the southern slope the Russian anti- aircraft guns captured a year ago were still in position, even though somewhat rusty. As soon as Hans Bunzel had snatched the Spornyy bridge from the Soviets, Lieutenant Klappich with the 3rd Battalion, 60th Motorized Infantry Regiment, drove up along the southern bank of the Manych in a dense blizzard and cautiously approached Samodurovka. Here too the Russians had already established a strongly protected bridgehead with units of their 2nd Mechanized Rifle Brigade—another dangerous base for the Soviet thrust against Bataysk. Klappich attacked. In fierce fighting he pushed on to the western edge of the village. The chief of staff of the Soviet brigade was taken prisoner.

SCORCHED EARTH by Paul Carell

To Be Continued:

Thank you for posting the von Mises letter: “Super-National Organization Held No Way to Peace.”

It was accidental. The usual Sunday review articles didn't inspire so I printed the editorial and letters pages since I hadn't done that for a while. I didn't even see the von Mises letter until I started cutting up the copies for posting.

Too bad he wasn't given the status of world's foremost economist instead of Keynes.

Be careful what you ask for . . .

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.