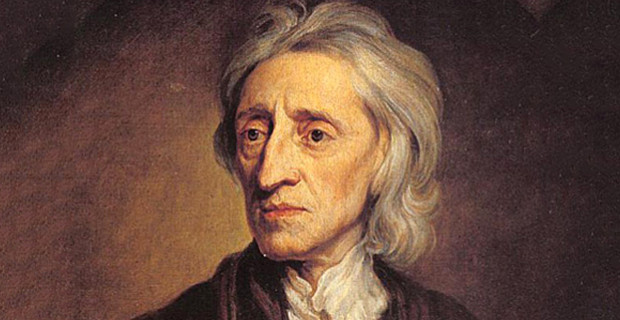

Often touted as a landmark text in the history of religious freedom, John Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) is remarkable in wisely limiting the power of “the magistrate … to do or meddle with nothing but barely in order to securing the civil peace and properties of his subjects,” and thus of granting “an absolute and universal right to toleration” concerning matters of “speculative opinions and divine worship.” In other words, the state has no power to compel belief or unbelief in any particular doctrine.

Still, the text is more complicated and limited in its vision of tolerance than the received tradition may suggest. For instance, with respect to “practical principles” of social action, there is also a claim to toleration “but yet only so far as they do not tend to the disturbance of the state”; that is, so long as these religious claims do not disturb or curtail the public interest. Fair enough, for certainly we do not suppose that religious freedom extends to harming others or interfering with the just exercise of law.

But when it comes to Catholics, Locke’s generosity shrivels, convinced as he is that Catholics refuse to be “subjects of any prince but the pope,” thus blurring the lines between speculation, worship, and “doctrines absolutely destructive to the society wherein they live.”

Locke considers his hostility warranted by two claims. First, because “where [papists] have power they think themselves bound to deny it to others”— since Catholic do not, he thinks, grant religious freedom to others, they do not deserve it themselves. Second, and what is more interesting at our cultural moment, Locke believes that Catholics do not, and cannot, be trusted to give genuine allegiance to the law since “they owe a blind obedience to an infallible pope, who has the keys of their consciences tied to his girdle, and can upon occasion dispense with all their oaths, promises and the obligations they have to their prince.” Governed ultimately by the pope, their allegiance is to a foreign prince, an authority other than the nation’s laws, and they are not quite faithful citizens.

Setting aside whether Locke understood Catholic thought, it’s notable that the limits of tolerance are defined by the state, and granted only insofar as the subjects do not claim, ultimately, a source of conscience independent of the state. After all, would not any dissenter from the civil religion who placed their conscience in some source other than the state by in the very same position, whether or not they were Roman Catholic? Might not, for instance, a Presbyterian or an evangelical who dissented from the Church of England—to take Locke’s context—because of their allegiance to Scripture view the authority of the law as relative, as not ultimate?

Flash forward to our own time and consider the oddity of how the HHS contraception mandate is playing itself out. On the one hand, we are told that religious freedom absolutely protects our freedom of worship and belief so long as the practical principles of social action flowing from belief into hospitals, schools, and charities are kept distinct and unblurred from religion. In the words of the Bishops, this “reduces freedom of religion to freedom of worship.”

And not just for Catholics. The odd case in New York City of Orthodox Jews being charged with violations of human rights since their insistence of a modest dress code within their stores was motivated by religious impulse. Similar dress codes could be found at all number of eateries and public establishments around the city, but because this code, according to the human rights commission, was religious in motivation it went from the tolerated world of worship and doctrine to the not-to-be-tolerated world of sociality. The same is working itself out in the various court cases about bed and breakfasts, bakers, and photographers with respect to gay marriage. Religious belief is tolerated if it is only thought and sung, but not if followed in public ways.

Now the obvious reason for this is that everyone has religious freedom, including, and most fundamentally, freedom from coercion. Basic to free exercise, it is thought, is immunity from anyone else moving into the sphere of sovereignty proper to each individual or association. True enough, but this seems inadequate to explain the fury of those who cannot believe or tolerate this “retrograde” Catholic refusal to formally cooperate with the provision of contraception and abortifacients.

Contraception, to limit our example, is easily available, inexpensive (often free), and legal, and the Church in the United States has launched no movement to overturn Griswold or make condoms illegal. And yet the rhetoric of suspicion about Catholics makes it seem as though a religious order’s refusal to pay for contraception is tantamount to a gross violation of a person’s right to be free from religious encroachment, even though the order has not suggested that those employed by their school or institution cannot buy or use contraception. As Judge Rovner put it in her dissent from the Seventh Circuit’s ruling in Korte and Grote, Catholic business owners refusing to cover contraception use their religious freedom “offensively rather than defensively.” But how is it a violation of someone’s liberty to not pay for their use of the Pill?

The answer seems endemic to a tension within the liberal order itself, as evidenced by Locke. Religion can be tolerated so long, but only so long, as it does not interfere with the public order or call the legitimacy of the state to define the public order for itself into question. That is, tame religions are tolerable, those which do not propose truths for the conscience of all.

When the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council were debating the Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis humanae, European bishops, particularly those from behind the Iron Curtain, were insistent in their interventions that the “public order” warrant for limiting and curtailing religion needed differentiation, in part because of their justified concern that the Soviets would use “public order” as a weapon against the Church. Consequently, the Declaration insists that any impeding of religion must be done for the sake of “just public order.” Again and again, the Declaration outlines that public order is not a blank check for the state, for the limitation must be just.

To put it another way, since religious liberty is a demand of the natural law, the limiting principle on religious freedom must also belong to the natural law. It must be a reasonable and naturally lawful ground to limit another’s religious exercise, and such a test is rather more robust than the vagaries of Locke’s claims about consciences tied to the Pope’s girdle.

In our own age, which is largely hostile to the natural law—even fearful of it—we should not be surprised to find our polity largely confused about what counts as religious freedom, what counts as a fair limit on another’s freedom, and what counts as the incursion of one’s religious exercise against another. In the great moral debates of our own time—abortion, embryo-destructive research, marriage, and others—we see this internal confusion of the Lockean tradition working itself out, namely, that religion is free so long as it’s about pious thoughts and incense, but once it appears in the streets, or laboratories, or chambers of law religion must serve the interests of the state, as defined by the state, and without reference to natural law.

Given this trajectory, there should be no surprise when members and institutions of traditional religions, whether Catholic, Protestant, or Jew, are presented with an understanding of religious freedom which tells them they must not think themselves entitled to speak or act in public, and certainly must not challenge the authority of the state.

And this, this is intolerable.

Editor’s note: The image of John Locke above was painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller in 1697.