Posted on 12/10/2019 5:05:52 AM PST by Homer_J_Simpson

Free Republic University, Department of History presents U.S. History, 1855-1860: Seminar and Discussion Forum

Bleeding Kansas, Dred Scott, Lincoln-Douglas, Harper’s Ferry, the election of 1860, secession – all the events leading up to the Civil War, as seen through news reports of the time and later historical accounts

First session: November 21, 2015. Last date to add: Sometime in the future.

Reading: Self-assigned. Recommendations made and welcomed.

Posting history, in reverse order

To add this class to or drop it from your schedule notify Admissions and Records (Attn: Homer_J_Simpson) by reply or freepmail.

WASHINGTON, December 10, 1859.

One week of congressional life is over, and I think it to be the stupidest business I was ever engaged in. We have done nothing in the Senate but discuss “John Brown,” “the irrepressible conflict,” and “the impending crisis,” and no one can imagine where the discussion will stop. The House of Representatives is still unorganized, and daily some members come near to blows. The members on both sides are mostly armed with deadly weapons, and it is said that the friends of each are armed in the galleries. The Capitol resounds with the cry of dissolution, and the cry is echoed throughout the city. And all this is simply to coerce, to frighten the Republicans and others into giving the Democrats the organization of the House. They will not succeed.

I called on Mrs. Trumbull to-day. She is the only woman I have spoken with since I came here. I called on another, to whose party I was invited the other day, and did not go; but she was not at home. You cannot imagine how I dislike this fashionable formality. It is terribly annoying, and I think I shall repudiate the whole thing.

SOURCE: William Salter, The Life of James W. Grimes, p. 121-2

ST. PETERSBURG, [RUSSIA], December 10,1859.

MY DEAR SIR; I wrote Mason a week or so ago and enclosed him his letter which I had published in the leading paper of this city, and you will now pardon me for enclosing you a letter in the same paper, the leading court paper, written from N[ew] York, and I would most respectfully call your attention to it, as it embraces exactly the current ideas that now prevail throughout Europe as to the weakness, of the South and the general belief that the North are about to “Conquer and subjugate the South.” We are looked upon and studiously represent as being in the condition of Mexico and the South American States. And I would cautiously suggest, that one leading object of McLain [?] in travelling in England and the Continent this last summer, was to spread these ideas, and most particularly to ascertain the feelings of the public men in England in reference to a rupture which he anticipated as certain. I will not say this certain, but it is my firm impression from various sources of information. We are certainly on the eve of very great events and I do not wish to be so presumptious as to advise any one in your distinguished position, but it does seem to me that it would be more impressive for Virginia to say less through newspapers and through them, to use more calm language and a firmer higher tone. She is a great state and has a great name. She made the Constitution and the Union, and she has a right to be heard. Under the circumstances in which she is placed, if the Legislature were, by a unanimous vote, to demand a Convention of the States, under the forms of the Constitution, and propose new Guarantees and a new League, giving security and peace to her, from the worst form of war, waged upon her, through the sanction of her border states, it would produce a profound impression. And if the South were to join in this demand, unless the Northern people immediately took decided steps themselves to put down forever the vile demagogues who have brought the country to the verge of ruin, a convention could not be resisted. And if after a full and truthful hearing, new securities and guarantees were refused, then the Southern States stand right before the world and posterity, in taking their own course to save their power and independence, be the consequences what they may.

Under the old articles of Confederation the Union had practically fallen to pieces and the wisest men thought it could not be saved, and yet in Convention of able and wise men, face to face and eye to eye, disclosing truthfully the dangers with which they were surrounded, the present Constitution was formed for a more perfect union and adopted by the States. So too now, when new dangers are developed, a full and manly discription in a Constitutional Convention of all the Statrs, may develop new remedies, and even a new league or covenant suited to the demands of the country. I merely suggest these things most respectfully, for I dread to see any hasty or ill-advised, ill conceived measures resorted to, which will end in bluster and confusion. Every thing ought to be done by the state as a state, with a full comprehension of the gravity of the matter and the momentous consequences involved. I think we ought to endeavor faithfully to save the Constitution and the Federal Union, if possible, and if not, then it is our duty to save ourselves. Even if the two sections were compelled to have separate internal organizations and separate Executives, still they might be united under a League or Covenant for all external and foreign intercourse, holding the free interchange of unrestricted internal and domestic trade as the basis of competing peace and union by interest. I merely throw out this idea, as I know your philosophical mind will readily comprehend it in all its details and bearings. It is a subject that I have thought of before, and it is forced up by the present unfortunate condition of affairs in our country. At this distance from home, I am filled with pain and apprehension for the future. I know and feel that we have arrived at a point where we will require stern and inflexible conduct united with thorough knowledge to carry us through safely. There is no time for ultraism of factious moves. There must be firmness and wisdom, and it must come from the States, and especially from Virginia moving as a state determined to protect her people and their rights, without the slightest reference to partizan contests of any kind whatever. Excuse me for writing thus freely, but our former relations justify it, and I sincerely desire to know the councils of wise and true men of the South. True I am here, but at the first tap of the drum I am ready for my own home and my own country.

* A Representative in Congress from South Carolina, 1834-1843.

SOURCE: Charles Henry Ambler, Editor, Correspondence of Robert M. T. Hunter, 1826-1876,p. 275-7

Rome, December 10, 1859.

Oh, best of governors, your letter of 18th ult., came swiftly to hand and relieved my anxiety (which was getting to be strong), lest you were sick, or some ailment had befallen your family. But the letter puts me at ease. Here I am rather rich in newspapers, so all the details of the Harper's Ferry affair are soon made known to us. See how the slave-holders hold their “bloody assizes” in Virginia! Well, the worse they behave the better for us and ours. This is the [illegible] – the beginning of birth-pains; the end is far enough away. How often I have wished I was in my old place, and at my old desk! But I too should have had to straighten a rope or else to flee off, no doubt, for it is not likely I could have kept out of harm's way in Boston. I sent a little letter to Francis Jackson, touching the matter which he will show you, perhaps. Wendell said some brave things, but, also some rash ones, which I am sorry for, but the whole was noble. B––– is faithful to his clerical instinct of cunning, not his personal of humanity; I read his sermon with a sad heart, and F–––'s with pain. Noble brave Garrison is true to himself as always, and says, “I am a non-resistant, and could not pull a trigger to free four million men, but Captain Brown in his fighting is faithful to his conscience, as I to mine, and acted as nobly as Cromwell, and Fayette and Washington; yes, more nobly, for his act was pure philanthropy. All honor to the fighting saint — now he is also a martyr!” That is the short of what the Liberator says.

The "Twenty-eighth" did not accept my resignation, but made some handsome resolutions. Perhaps it is better so. Yet sure I am that my preaching days are all over and left behind me, even if my writing and breathing time continue, which I think will not last long.

I do all I can to live, but make all my calculations for a (not remote) termination of my work here. I buy no books, except such as are indispensable to keep me from eating my own head off.

Miss Cushman is here, and very kind to me; the Storys most hospitable people as well as entertaining; we all dined there on Thanksgiving day. Dr. Appleton (of Boston) has helped me to many things. I have seen Mrs. Crawford, and of course all the American artists, painters, and sculptors, The Brownings came a few days ago, and I have seen them both. I like her much! He, too, seems a good fellow, full of life; intense Italians are they both.

SOURCE: John Weiss, Life and correspondence of Theodore Parker, Volume 2, p. 389-90

As always, a fascinating contemporary view of what started as journalism and then became history.

Thanks for this.

Note the last item on page 17, “South Carolina Ready for Secession.”

Washington Irving might be considered the first American superstar author. He is buried at Sleepy Hollow. :0

It sounds crazy 150 years later, being willing to put the Union asunder just to keep the right own people as property.

Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1859-1865, edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher

I have just been to church, and heard a long and not remarkably entertaining sermon.

I have about as much as I can do to restrain myself from plunging into the debate in the Senate on John Brown, but I exercise self-denial, and do not.

SOURCE: William Salter, The Life of James W. Grimes, p. 122

DEAR GENERAL: . . . Late last night I got the dispatch that the books have been shipped; so I think we may safely count on them in time. I could only after long search find four of the French grammars required by Monsieur St. Ange. So of necessity had to telegraph for one hundred. The steamer leaves New York to-day and ought to be here the 22nd and at Alexandria by the 1st - rather close cutting for us.

All other things I have purchased here. Many things went on Friday by the “Rapides.” I will bring some tomorrow in the “Telegram” and balance will follow next week in the “Rapides.” I have paid in full all bills but furniture and have paid $1,000 toward furniture out of about $1,500. I have drawn only $1,920, but will buy about $50 more of little odds and ends, and bring with me in cash to make up the $2,500. The balance will remain to your credit, and I think you had better meet me at the Seminary about Friday to examine the bills and receipts, to receive the cash I bring up, and to see the kind and quality of furniture. I hear your letter-press, book, brush, etc., cost about $13. You had better come with your buggy and receive it. It had, for convenience, to go with our packages. I have sent up a cooking range, cost $175, and want Jarreau forthwith to move one or more servants out to clean up and get ready.

Many of these items of purchase were hard to find, and my time has been too much taken up to enable me to attempt to make acquaintances. I dined yesterday with your friends, the Frerets, who had many kind inquiries for you.

I have a drum and drummer, also a fife, but thus far have failed to get a tailor or shoemaker. I have examined shoes, boots, clothing, cloth, etc., and know exactly how to order when the time comes.

I have a letter from Bragg which I will show you; he coincides with you in the necessity of making a military academy by law, and wants you to meet him in January at Baton Rouge. Our first paramount duty is to start on present economical basis and enlarge as means are provided. It is easy to increase, but hard to curtail. Unless it be convenient for you to come over, write me at the Seminary, to bring in your press, money, and accounts, and appoint a day and hour, for I must work smart as you know.

SOURCES: Walter L. Fleming, General W.T. Sherman as College President, p. 74-5

NEW ORLEANS, Sunday, Dec. 12.

. . . I am stopping at the City Hotel which is crowded and have therefore come to this my old office, now Captain Kilburn's, to do my writing. I wish I were here legitimately, but that is now past, and I must do the best in the sphere in which events have cast me. All things here look familiar, the streets, houses, levees, drays, etc., and many of the old servants are still about the office, who remember me well, and fly round at my bidding as of old.

I have watched with interest the balloting for speaker, with John as the Republican candidate. I regret he ever signed that Helper book, of which I know nothing but from the extracts bandied about in the southern papers. Had it not been for that, I think he might be elected, but as it is I do not see how he can expect any southern votes, and without them it seems that his election is impossible. His extreme position on that question will prejudice me, not among the supervisors, but in the legislature where the friends of the Seminary must look for help. Several of the papers have alluded to the impropriety of importing from the north their school teachers, and if in the progress of debate John should take extreme grounds, it will of course get out that I am his brother from Ohio, universally esteemed an abolition state, and they may attempt to catechize me, to which I shall not submit.

I will go on however in organizing the Seminary and trust to the future; but hitherto I have had such bad luck, in California and New York, that I fear I shall be overtaken here by a similar catastrophe. Of course there are many here such as Bragg, Hebert, Graham, and others that know that I am not an abolitionist. Still if the simple fact be that my nativity and relationship with Republicans should prejudice the institution, I would feel disposed to sacrifice myself to that fact, though the results would be very hard, for I know not what else to do.

If the Southern States should organize for the purpose of leaving the Union I could not go with them. If that event be brought about by the insane politicians I will ally my fate with the north, for the reason that the slave question will ever be a source of discord even in the South. As long as the abolitionists and the Republicans seem to threaten the safety of slave property so long will this excitement last, and no one can foresee its result; but all here talk as if a dissolution of the Union were not only a possibility but a probability of easy execution. If attempted we will have Civil War of the most horrible kind, and this country will become worse than Mexico.

What I apprehend is that because John has taken such strong grounds on the institution of slavery that I will first be watched and suspected, then maybe addressed officially to know my opinion, and lastly some fool in the legislature will denounce me as an abolitionist spy because there is one or more southern men applying for my place.

I am therefore very glad you are not here, and if events take this turn I will act as I think best. As long as the United States Government can be maintained in its present form I will stand by it; if it is to break up in discord, strife and Civil War, I must either return to California, Kansas or Ohio. My opinions on slavery are good enough for this country, but the fact of John being so marked a Republican may make my name so suspected that it may damage the prospects of the Seminary, or be thought to do so, which would make me very uncomfortable. . .

SOURCES: Walter L. Fleming, General W.T. Sherman as College President, p. 75-7

NEW ORLEANS, Sunday, Dec. 12.

DEAR BROTHER: . . . I have watched the despatches, which are up to Dec. 10, and hoped your election would occur without the usual excitement, and believe such would have been the case had it not been for your signing for that Helper's book. Of it I know nothing, but extracts made copiously in southern papers show it to be not only abolition but assailing. Now I hoped you would be theoretical and not practical, for practical abolition is disunion, Civil War, and anarchy universal on this continent, and I do not believe you want that. . . I do hope the discussion in Congress will not be protracted, and that your election, if possible, will occur soon. Write me how you came to sign for that book. Now that you are in, I hope you will conduct yourself manfully. Bear with taunts as far as possible, biding your time to retaliate. An opportunity always occurs.

SOURCES: Walter L. Fleming, General W.T. Sherman as College President, p. 77-8

PITTSBURG, PA., December 12, 1859.

MR. C. M. CLAY —

DEAR FRIEND: — I am still in the free States, being detained longer than I expected. My health is better than when I left home. We shall raise money enough to pay for our land, and open the way for other more extended interests.

I find Republicanism rising. The Republicans in Philadelphia have separated from the “mere peoples’ party.” They are going into the work in good earnest. I stopped with some true friends of yours, Wm. B. Thomas and Professor Cleveland. Many inquired for you. I told them you were still in the field, and the true friend of freedom. I believe this, and I am pained when I hear Republicans talk of such men as Bates, Blair, etc., and omit your name.

I have repeatedly spoken of you in public and private. I think the spirit is rising in the Republican ranks, and will yet demand a representative man. If you or Chase or Seward are on the ticket, or tried men, I shall expect to work with the Republicans. I shall continue to do all I can to urge a higher standard. Wm. B. Thomas of Philadelphia says he will thus work and expend money to induce a higher standard; but, if the party “flattens down” below what it was last time, he is off. Hundreds of others will do the same — yes, thousands; and that class of men the party can not well do without.

Dr. Hart of New York proposed that I address a letter to you, calling you out. I thought it not best to do so until I should see you personally, or write to you, and have an arrangement. I am having encouraging audiences — staying longer than I had intended — perhaps ’tis all well. I learn there is some feeling against me in Kentucky in consequence of an article in the Louisville Courier, representing me as approving John Brown's course, etc. Such is a direct perversion of my uniform and invariable teaching. I have been careful here, and always said I disapproved his manner of action — attempts to abduct, or incite insurrection; but that I thought God is speaking to the world through John Brown, in his spirit of consecration. I suppose I can not help the gullibility of the people, unless I attempt to correct by publishing. Is this best? Write to me at Cincinnati, care of Geo. L. Weed. I shall start for Lewis in a day or two; from thence to Cincinnati, and home.

JOHN. G. FEE.

SOURCE: Cassius Marcellus Clay, The life of Cassius Marcellus Clay, Volume 1, p. 575-6

SHADY HILL, 13 December, 1859.

... I have thought often of writing to you, — especially since John Brown made his incursion into Virginia, — but it has been difficult hitherto to form a dispassionate judgment in regard to this affair, and I have not cared to write a mere expression of personal feeling. Perhaps it is even now still too near the event for one to balance justly all the considerations involved in it. Unless you have seen some one of the American papers during the last two months you can hardly have formed an idea of the intensity of feeling and interest which has prevailed throughout the country in regard to John Brown. I have seen nothing like it. We get up excitements easily enough, but they die away usually as quickly as they rose, beginning in rhetoric and ending in fireworks; but this was different. The heart of the people was fairly reached, and an impression has been made upon it which will be permanent and produce results long hence.

When the news first came, in the form of vague and exaggerated telegraphic reports, of the seizure of the Arsenal at Harper's Ferry, people thought it was probably some trouble among the workmen at the place; but as the truth slowly came out and John Brown's name, which was well known through the country, was mentioned as that of the head of the party, the general feeling was that the affair was a reckless, merely mad attempt to make a raid of slaves, — an attempt fitly put down by the strong arm. There was at first no word of sympathy either for Brown or his undertaking. But soon came the accounts of the panic of the Virginians, of the cruelty with which Brown's party were massacred; of his noble manliness of demeanour when, wounded, he was taken prisoner, and was questioned as to his design; of his simple declarations of his motives and aims, which were those of an enthusiast, but not of a bad man, — and a strong sympathy began to be felt for Brown personally, and a strong interest to know in full what had led him to this course. Then the bitterness of the Virginia press, the unseemly haste with which the trial was hurried on, — and all the while the most unchanged, steady, manliness on the part of "Old Brown," increased daily the sympathy which was already strong. The management of the trial, the condemnation, the speech made by Brown, the letters he wrote in prison, the visit of his wife to him, — and at last his death, wrought up the popular feeling to the highest point. Not, indeed, that feeling or opinion have been by any means unanimous; for on the one side have been those who have condemned the whole of Brown's course as utterly wicked, and regarded him as a mere outlaw, murderer, and traitor, while, on the other, have been those who have looked upon his undertaking with satisfaction, and exalted him into the highest rank of men. But, if I am not wrong, the mass of the people, and the best of them, have agreed with neither of these views. They have, while condemning Brown's scheme as a criminal attempt to right a great wrong by violent measures, and as equally ill-judged and rash in execution, felt for the man himself a deep sympathy and a fervent admiration. They have admitted that he was guilty under the law, that he deserved to be hung as a breaker of the law, — but they have felt that the gallows was not the fit end for a life like his, and that he died a real martyr in the cause of freedom.

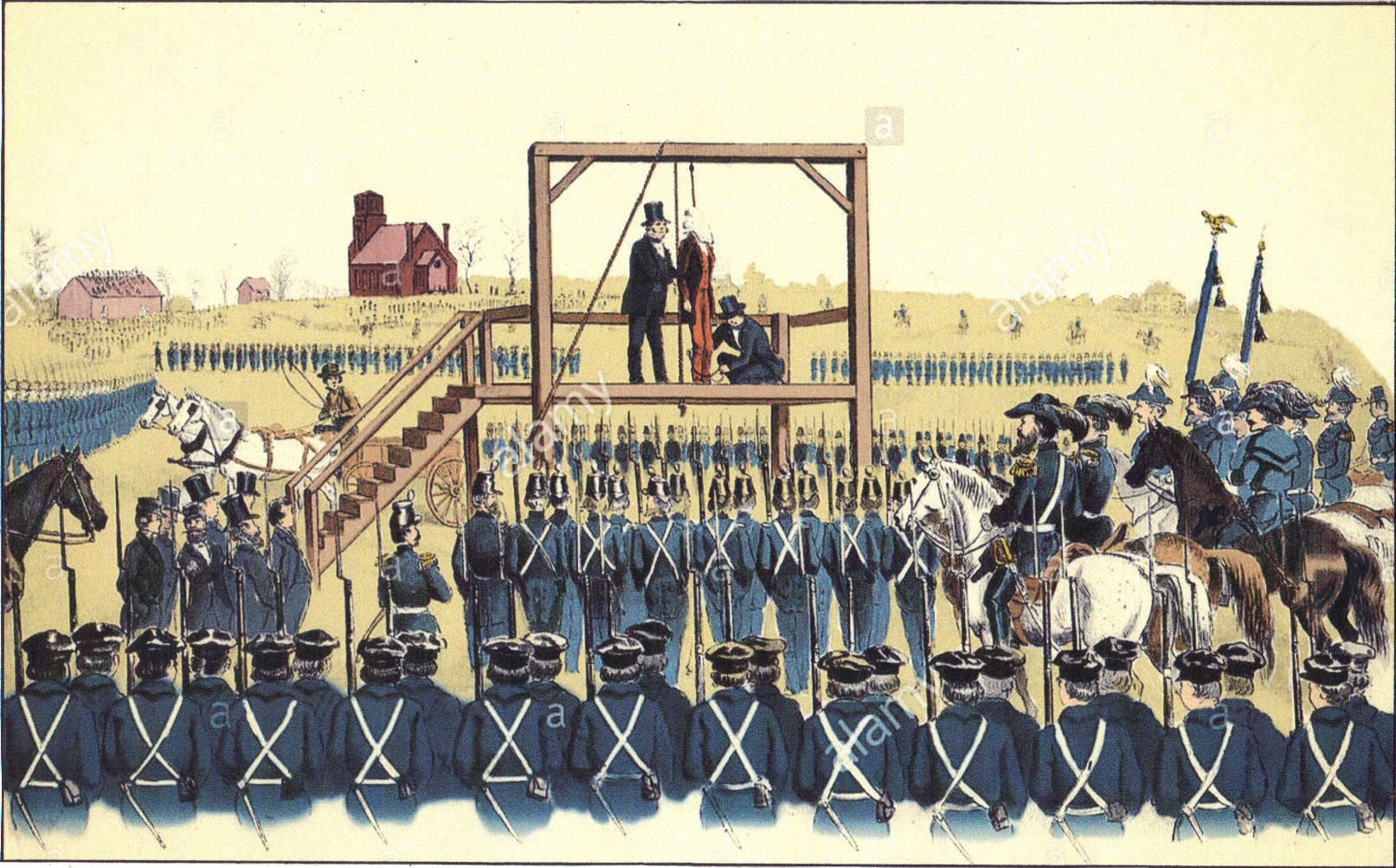

Brown in truth was a man born out of time. He was of a rare type, rare especially in these days. He belonged with the Covenanters, with the Puritans. He was possessed with an idea which mastered his whole nature and gave dignity and force to his character. He had sincere faith in God, — and especially believed in the sword of the Lord. His chief fault seems to have been impatience with the slowness of Providence. Seeing what was right he desired that it should instantly be brought to pass, — and counted as the enemies of the Lord those who were opposed to him. But the earnestness of his moral and religious convictions and the sincerity of his faith made him single-minded, and manly in the highest degree. There was not the least sham about him; no whining over his failure; no false or factitious sentiment, no empty words; — in everything he showed himself simple, straightforward and brave. The Governor of Virginia, Governor Wise, said of him, that he was the pluckiest man he had ever seen. And on the morning of his execution, the jailor riding with him to the gallows said to him, — “You 're game, Captain Brown.” And game he was to the very last. He said to the sheriff as he stepped onto the platform of the gallows, “Don't keep me waiting longer than is necessary,” — and then he was kept waiting for more than ten minutes while the military made some movement that their officers thought requisite. This gratuitous piece of cruel torture has shocked the whole country. But Brown stood perfectly firm and calm through the whole.

The account of his last interview with his wife before his death, which came by telegraph, was like an old ballad in the condensed picturesqueness of its tender and tragic narrative.

You see even from this brief and imperfect statement of mine, how involved the moral relations of the whole affair have been, and how difficult the questions which arise from it are to answer.

What its results will be no one can tell, but they cannot be otherwise than great. One great moving fact remains that here was a man, who, setting himself firm on the Gospel, was willing to sacrifice himself and his children in the cause of the oppressed, or at least of those whom he believed unrighteously held in bondage. And this fact has been forced home to the consciousness of every one by Brown's speech at his trial, and by the simple and most affecting letters which he wrote during his imprisonment. The events of this last month or two (including under the word events the impression made by Brown's character) have done more to confirm the opposition to Slavery at the North, and to open the eyes of the South to the danger of taking a stand upon this matter opposed to the moral convictions of the civilized world, — than anything which has ever happened before, than all the anti-slavery tracts and novels that ever were written.

I do not believe that other men are likely to follow John Brown in the course which he adopted, — mainly because very few of them are of his stamp, but also because almost all men see that the means he adopted were wrong. But the magnanimity of the man will do something to raise the tone of national character and feeling, — and to set in their just position the claims and the pretensions of the mass of our political leaders. John Brown has set up a standard by which to measure the principles of public men. . . .

SOURCE: Sara Norton and M. A. DeWolfe Howe, Letters of Charles Eliot Norton, Volume 1, p. 197-201

Continued from December 11 (reply #8.)

Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1859-1865, edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher

WASHINGTON, December 14, 1859.

MY DEAR SIR: Pray, if you can, talk with Mr. Weed about Mrs. B.'s case. Twice I have tried to see him, but he has now left town.

I am in constant communication with members on this matter, and find response. But as yet no person is fixed upon in whose name Mrs. B. can be represented. Perhaps this cannot be done till after the election of Speaker.

I have always insisted that no arrangement should be permitted which did not recognize Mrs. B.

Tell the Count that I always welcome him and all that he can say. But I have no personal griefs to dwell on. I have suffered. But what is all this compared with the cause? On sait assez qu'on ne doit guere parler de sa femme; mais on ne sait pas assez qu’ on ne doit guère parler de soi. This is Rochefoucauld, and the Count will agree in it.

CHARLES SUMNER.

SOURCE: James Shepherd Pike, First Blows of the Civil War: The Ten Years of Preliminary Conflict in the United States from 1850 to 1860, p. 454

Bryant and Bigelow were both editors of the New York Evening Post.

NEW YORK, December 14, 1859.

Probably Mr. Seward stays in Europe till the first flurry occasioned by the Harper's Ferry affair is over; but I do not think his prospects for being the next candidate for the Presidency are brightening. This iteration of the misconstruction put on his phrase of “the irrepressible conflict between freedom and slavery” has, I think, damaged him a good deal, and in this city there is one thing which has damaged him still more. I mean the project of Thurlow Weed to give charters for a set of city railways, for which those who receive them are to furnish a fund of from four to six hundred thousand dollars, to be expended for the Republican cause in the next Presidential election. This scheme was avowed by Mr. Weed to our candidate for mayor, Mr. Opdyke, and others, and shocked the honest old Democrats of our party not a little. Besides the Democrats of our party, there is a bitter enmity to this railway scheme cherished by many of the old Whigs of our party. They are very indignant at Weed's meddling with the affair, and between Weed and Seward they make no distinction, assuming that, if Seward becomes President, Weed will be “viceroy over him.” Notwithstanding, I suppose it is settled that Seward is to be presented by the New York delegation to the convention as their man.

Frank Blair, the younger, talks of Wade, of Ohio, and it will not surprise me if the names which have been long before the public are put aside for some one against which fewer objections can be made.

Our election for mayor is over. We wished earnestly to unite the Republicans on Havemeyer, and should have done so if he had not absolutely refused to stand when a number of Republicans waited on him, to beg that he would consent to stand as a candidate.

Just as the Republicans had made every arrangement to nominate Opdyke, he concluded to accept the Tammany nomination, and then it was too late to bring the Republicans over. They had become so much offended and disgusted with the misconduct of the Tammany supervisors in appointing registrars, and the abuse showered upon the Republicans by the Tammany speakers, and by the shilly-shallying of Havemeyer, that they were like so many unbroke colts; there was no managing them. So we had to go into a tripartite battle; and Wood, as we told them beforehand, carried off what we were quarrelling for. Havemeyer has since written a letter to put the Republicans in the right. “He is too old for the office,” said many persons to me when he was nominated. After I saw that letter I was forced to admit that this was true.

Your letters are much read. I was particularly, and so were others, interested with the one — a rather long one — on the policy of Napoleon, but I could not subscribe to the censure you passed on England for not consenting to become a party to the Congress unless some assurance was given her that the liberties of Central Italy would be secured. By going into the Congress she would become answerable for its decisions, and bound to sustain them, as she was in the arrangements made by her and the other great powers after the fall of Napoleon — arrangements the infamy of which has stuck to her ever since. I cannot wonder that she is shy of becoming a party to another Congress for the settlement of the affairs of Europe, and I thought that reluctance did her honor. I should have commented on your letter on this subject if it had been written by anybody but yourself. . . .

The Union-savers, who include a pretty large body of commercial men, begin to look on our paper with a less friendly eye than they did a year ago. The southern trade is good just now, and the western rather unprofitable. Appleton says there is not a dollar in anybody's pocket west of Buffalo.

SOURCE: Parke Godwin, A Biography of William Cullen Bryant, Volume 2, p. 127-8

The Diary of George Templeton Strong, Edited by Allan Nevins and Milton Halsey Thomas

SEMINARY OF LEARNING, Alexandria, Dec. 15,1859.

My DEAR SIR: . . . I wrote you some time ago, addressed to Mount Lebanon, advising you to come on at once, to get in position before, we will be all in confusion by the arrival of the cadets. All the professors are now here at hand but yourself, and I think you should come on at once. I have just returned from New Orleans where I purchased all the room furniture for cadets, but I bought nothing for professors, and advise you to bring your bedding, indeed any furniture you may have, as Alexandria is a poor place to supply. I think you will be as comfortable here, and your health be restored as fast as anywhere in the state. All books must be ordered from New York. I found the supply in New Orleans very poor, and we want a list of your first text books, grammar, and dictionary as soon as possible, that they may be ordered, but, as I suppose we can fully employ the students the first few months in French and Algebra, I will now await your coming.

The want of certainty has caused many to doubt whether we could commence January 2, but you may announce that it is as certain as that the day will come. About thirty-four appointments have been made by the Board of Supervisors. I suppose sixteen will have been made by the governor. So you see thus far we have not an adequate supply of cadets. The right to appoint rests in the Board of Supervisors, but I know their views so well, and there being no time for formalities you may notify Mr. Gladney, and indeed any young men between fifteen and twenty-one, who can read and write, and who have some notion of arithmetic (addition, etc., as far as decimal fractions) to come on by January second and we will procure for them the appointment and receive them.

Each young man should be of good character with a trunk and fair supply of clothing, and must deposit two hundred dollars for six months' expenses in advance. We think we can make the aggregate year's expenses fall within four hundred dollars.

I wrote and sent you circulars to Mount Lebanon which I infer you did not receive. No cadet can be received except from Louisiana.

Please state these leading facts to some prominent gentleman of your neighborhood, assure them that its success is determined on, and that as soon as the Academic Board can meet, deliberate, and refer their work to a Board of Supervisors, full rules and regulations will be adopted, published and adhered to. Until that time we can hardly assert exactly what are our text books, or what the order of exercises.

It is however determined that the Seminary shall be governed by the military system, which far from being tyrannical or harsh is of the simplest character, easiest of enforcement and admits of the most perfect control by the legislature.

SOURCES: Walter L. Fleming, General W.T. Sherman as College President, p. 78-80

What timely remarks! I wonder how Ben Shapiro or Ann Coulter would respond.

Very good question. If I hadn’t been booted off Twitter for triggering speech I would ask them. Well, Shapiro anyway.

It sounds like George is saying that certain types of speech are so dangerous they should be stopped by mob violence, but he’s not going to get his own hands dirty ... that’s what Irish are for!

That’s the very reasoning used by students who claim to be traumatized by the very existence of Ben Shapiro. One student’s roommate claimed to be “unsafe” because the other guy was watching a Ben Shapiro video in his room.

Is Ben Shapiro in the same league as Wendell Phillips and William Lloyd Garrison? Too soon to tell. Ask me in 160 years.

It seems to me that there’s a big difference that isn’t particularly about whether Phillips and Garrison, or Lyman Beecher or other radical abolitionists, were more intellectually impressive or philosophically correct than Ben Shapiro, or, say, Jordan Peterson or Charles Murray.

Rather, the abolitionists had a Big Issue with a lot of firepower - literally and figuratively - on both sides of general slavery question as well as in subtopics such as gradual abolition, “die on the vine,” or the encouragement of slave revolts.

Shapiro et al are simply trying to be allowed to say obviously factual things to people who have gone ga-ga and insist everyone pretend their delusions are true.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.