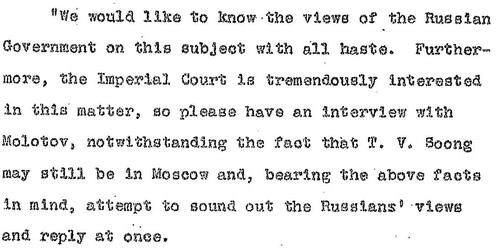

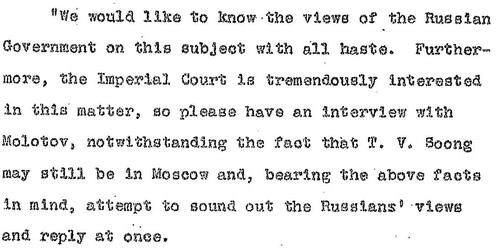

An excerpt from a July 12, 1945 US War Department summary of an intercepted cable from Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo to his ambassador to Russia

Posted on 08/06/2023 7:01:59 PM PDT by SeekAndFind

The anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki present an opportunity to demolish a cornerstone myth of American history — that those twin acts of mass civilian slaughter were necessary to bring about Japan’s surrender, and spare a half-million US soldiers who’d have otherwise died in a military conquest of the empire’s home islands.

Those who attack this mythology are often reflexively dismissed as unpatriotic, ill-informed or both. However, the most compelling witnesses against the conventional wisdom were patriots with a unique grasp on the state of affairs in August 1945 — America’s senior military leaders of World War II.

Let’s first hear what they had to say, and then examine key facts that led them to their little-publicized convictions:

General Dwight Eisenhower on learning of the planned bombings: “I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and voiced to [Secretary of War Stimson] my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face’.”

Admiral William Leahy, Truman's Chief of Staff: “The use of this barbarous weapon…was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.”

Major General Curtis LeMay, 21st Bomber Command: “The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb…The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.”

General Hap Arnold, US Army Air Forces: “The Japanese position was hopeless even before the first atomic bomb fell, because the Japanese had lost control of their own air.” “It always appeared to us that, atomic bomb or no atomic bomb, the Japanese were already on the verge of collapse.”

Ralph Bird, Under Secretary of the Navy: “The Japanese were ready for peace, and they already had approached the Russians and the Swiss…In my opinion, the Japanese war was really won before we ever used the atom bomb.”

Brigadier General Carter Clarke, military intelligence officer who prepared summaries of intercepted cables for Truman: “When we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it…we used [Hiroshima and Nagasaki] as an experiment for two atomic bombs. Many other high-level military officers concurred.”

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, Pacific Fleet commander: “The use of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender.”

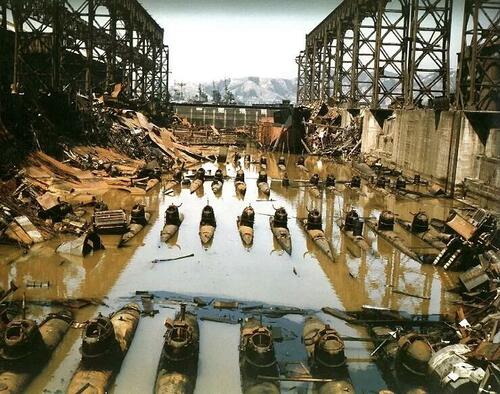

Putting out feelers through third-party diplomatic channels, the Japanese were seeking to end the war weeks before the atomic bombings on August 6 and 9, 1945. Japan’s navy and air forces were decimated, and its homeland subjected to a sea blockade and allied bombing carried out against little resistance.

The Americans knew of Japan’s intent to surrender, having intercepted a July 12 cable from Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo, informing Japanese ambassador to Russia Naotake Sato that “we are now secretly giving consideration to the termination of the war because of the pressing situation which confronts Japan both at home and abroad.”

Togo told Sato to “sound [Russian diplomat Vyacheslav Molotov] out on the extent to which it is possible to make use of Russia in ending the war.” Togo initially told Sato to obscure Japan’s interest in using Russia to end the war, but just hours later, he withdrew that instruction, saying it would be “suitable to make clear to the Russians our general attitude on ending the war”— to include Japan’s having “absolutely no idea of annexing or holding the territories which she occupied during the war.”

An excerpt from a July 12, 1945 US War Department summary of an intercepted cable from Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo to his ambassador to Russia

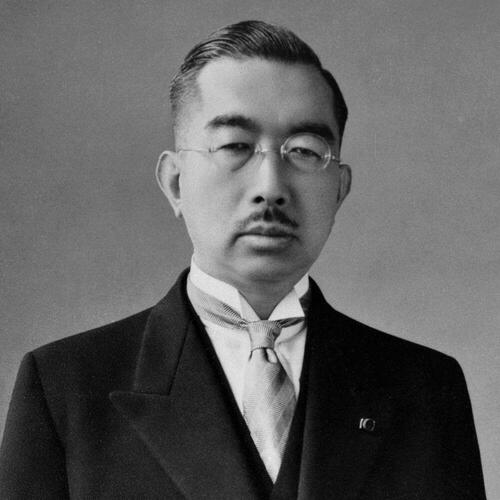

Japan’s central concern was the retention of its emperor, Hirohito, who was considered a demigod. Even knowing this — and with many US officials feeling the retention of the emperor could help Japanese society through its postwar transition —the Truman administration continued issuing demands for unconditional surrender, offering no assurance that the emperor would be spared humiliation or worse.

In a July 2 memorandum, Secretary of War Henry Stimson drafted a terms-of-surrender proclamation to be issued at the conclusion of that month’s Potsdam Conference. He advised Truman that, “if…we should add that we do not exclude a constitutional monarchy under her present dynasty, it would substantially add to the chances of acceptance.”

Truman and Secretary of State James Byrnes, however, continued rejecting recommendations to give assurances about the emperor. The final Potsdam Declaration, issued July 26, omitted Stimson’s recommended language, sternly declaring, “Following are our terms. We will not deviate from them.”

One of those terms could reasonably be interpreted as jeopardizing the emperor: “There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest.”

Japanese emperor Hirohito reigned from 1926 to 1989

At the same time the United States was preparing to deploy its formidable new weapons, the Soviet Union was moving armies from the European front to northeast Asia.

In May, Stalin told the US ambassador that Soviet forces should be positioned to attack the Japanese in Manchuria by August 8. In July, Truman predicted the impact of the Soviets opening a new front. In a diary entry made during the Potsdam Conference, he wrote that Stalin assured him “he’ll be in the Jap War on August 15th. Fini Japs when that comes about.”

Right on Stalin’s original schedule, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan two days after the August 6 bombing of Hiroshima. That same day — August 8 — Emperor Hirohito told the country’s civilian leaders that he still wanted to pursue a negotiated surrender that would preserve his reign.

On August 9, Soviet attacks commenced on three fronts. News of Stalin’s invasion of Manchuria prompted Hirohito to call a new meeting to discuss surrender — at 10 am, one hour before the strike on Nagasaki. The final surrender decision came on August 10.

Three-year old Shinichi Tetsutani, burned as he was riding this tricycle when the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima, died a painful death that night (Hiroki Kobayashi/National Geographic)

The Soviet timeline makes the atomic bombings all the more troubling: One would think a US government that’s appropriately hesitant to incinerate and irradiate hundreds of thousands of civilians would want to first see how a Soviet declaration of war affected Japan’s calculus.

As it turns out, the Japanese surrender indeed appears to have been prompted by the Soviet entry into the war on Japan — not by the atomic bombs. “The Japanese leadership never had photo or video evidence of the atomic blast and considered the destruction of Hiroshima to be similar to the dozens of conventional strikes Japan had already suffered,” wrote Josiah Lippincott at The American Conservative.

Sadly, the evidence points to a US government determined to drop atomic bombs on Japanese cities as an end in itself, to such an extent that it not only ignored Japan’s interest in surrender, but worked to ensure that surrender was delayed until after upwards of 210,000 people — disproportionately women, children and elderly — were killed in the two cities.

Make no mistake: This was a deliberate targeting of civilian populations. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were chosen because they were pristine, and could thus fully showcase the bombs’ power. Hiroshima was home to a small military headquarters, but the fact that both cities had gone untouched by a strategic bombing campaign that began 14 months earlier certifies their military and industrial insignificance.

“The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing,” Eisenhower would later say. “I hated to see our country be the first to use such a weapon.”

According to his pilot, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of US Army Forces Pacific, was “appalled and depressed by this Frankenstein monster.”

“When I asked General MacArthur about the decision to drop the bomb,” wrote journalist Norman Cousins, “I was surprised to learn he had not even been consulted…He saw no military justification for the dropping of the bomb. The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.”

What then, was the purpose of devastating Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs?

A key insight comes from Manhattan Project physicist Leo Szilard. In 1945, Szilard organized a petition, signed by 70 Manhattan Project scientists, urging Truman not to use atomic bombs against Japan without first giving the country a chance to surrender, on terms that were made public.

In May 1945, Szilard met with Secretary of State Byrnes to urge atomic restraint. Byrnes wasn’t receptive to the plea. Szilard — the scientist who’d drafted the pivotal 1939 letter from Albert Einstein urging FDR to develop an atomic bomb — recounted:

"[Byrnes] was concerned about Russia's postwar behavior. Russian troops had moved into Hungary and Rumania, and Byrnes thought it would be very difficult to persuade Russia to withdraw her troops from these countries, that Russia might be more manageable if impressed by American military might, and that a demonstration of the bomb might impress Russia."

Whether the atomic bomb’s audience was in Tokyo or Moscow, some in the military establishment championed alternative ways to demonstrate its power.

Lewis Strauss, Special Assistant to the Navy Secretary, said he proposed “that the weapon should be demonstrated over… a large forest of cryptomeria trees not far from Tokyo. The cryptomeria tree is the Japanese version of our redwood… [It] would lay the trees out in windrows from the center of the explosion in all directions as though they were matchsticks, and, of course, set them afire in the center. It seemed to me that a demonstration of this sort would prove to the Japanese that we could destroy any of their cities at will.”

Strauss said Navy Secretary Forrestal “agreed wholeheartedly,” but Truman ultimately decided an optimal demonstration required burning hundreds of thousands of noncombatants and laying waste to their cities. The buck stops there.

A victim of the atomic bomb

The particular means of inflicting these mass murders — a solitary object dropped from a plane at 31,000 feet — helps warp Americans’ evaluation of its morality. Using an analogy, historian Robert Raico cultivates ethical clarity:

“Suppose that, when we invaded Germany in early 1945, our leaders had believed that executing all the inhabitants of Aachen, or Trier, or some other Rhineland city would finally break the will of the Germans and lead them to surrender. In this way, the war might have ended quickly, saving the lives of many Allied soldiers. Would that then have justified shooting tens of thousands of German civilians, including women and children?”

The claim that dropping the atomic bombs saved a half-million American lives is more than just empty: Truman’s stubborn refusal to provide advance assurances about the retention of Japan’s emperor arguably cost American lives.

That’s true not only of a war against Japan that lasted longer than it needed to, but also of a Korean War precipitated by the US-invited Soviet invasion of Japanese-held territory in northeast Asia. More than 36,000 US service members died in the Korean War — among a staggering 2.5 million total military and civilian dead on both sides of the 38th Parallel.

We like to think of our system as one in which the supremacy of civilian leaders acts as a rational, moderating force on military decisions. The needless atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — against the wishes of World War II’s most revered military leaders — tells us otherwise.

Sadly, the destructive effects of the Hiroshima myth aren’t confined to Americans’ understanding of events in August 1945. “There are hints and notes of the Hiroshima myth that persist all through modern times,” State Department whistleblower and author Peter Van Buren said on The Scott Horton Show.

The Hiroshima myth fosters a depraved indifference to civilian casualties associated with US actions abroad, whether it’s women and children slaughtered in a drone strike in Afghanistan, hundreds of thousands dead in an unwarranted invasion of Iraq, or a baby who dies for lack of imported medicine in US-sanctioned Iran.

Ultimately, to embrace the Hiroshima myth is to embrace a truly sinister principle: That, in the correct circumstances, it’s right for governments to intentionally harm innocent civilians. Whether the harm is inflicted by bombs or sanctions, it’s a philosophy that mirrors the morality of al Qaeda.

That’s not the only thread connecting 1945 to 2023, as Truman’s insistence on unconditional surrender is echoed by the Biden administration’s utter disinterest in pursuing a negotiated peace in Ukraine.

Today, confronting an adversary with 6,000 nuclear warheads — each a thousand times more powerful than the bombs dropped on Japan — Biden’s own stubborn perpetuation of war puts us all at risk of sharing the fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s innocents.

Well stated. I follow you.

Mine as well. Kindof sounds like all the naysayers after the Iraq war.

these revisionists are acting like there was nothing going on in the world at that time...like the bombing was all done on a lark. Again, 60 MILLION had already died. Phillip Morrison, physicist who worked at Los Alamos, said they would turn on the BBC everyday...not to listen to the news, but to make sure London still existed. Hitler was sending V2 rockets there....nobody knew for sure what anybody had.

I've been saying the same thing for years. Dresden and Hamburg were pretty much leveled. I can't think of the third German city that was bombed into the ground. There were no innocent civilians on either side in those days of all out warfare. It was destroy the enemy by any means.

And like many have mentioned here, after my Father's Army beat Hitler and Mussolini, were told they were headed to Japan. He once told me he was so grateful we nuked Japan. He and every solder, Army Air Corp, knew they were heading to their deaths in Japan.

It was widely known by our troops in Europe about the fanatical training of every Japanese citizen to defend their Emperor who they considered a god. It would have been a slaughter on both sides. It would have made Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, Okinawa, Peleiu, Saipan look like skirmishes. Those Jap crazies had to be nuked twice. Good.

There are plenty of radio broadcasts that reported all the celebrations in the streets here in the US after the Japs surrendered.

Believe me, those folks loved the bomb.

As I posted earlier I was 13 and the adults were thrilled………war over .

….

i think it was Cologne....

Me too...

:)

After doing some quick research, yes, Cologne was pretty much leveled. However, I was thinking of Hanover or Nuremberg.

I'm no expert on WWII, but the above cities were legitimate targets because Germany had countless factories, ammo depots, and transport systems all over the country. All fair targets.

I've read some about how Hitler came to power, but it's still confusing to me how he pulled Germany together in such a short time after WWI. It's probably a case study regarding political charisma building on patriotic sensibilities.

One of my biggest problems with WWII in Europe and the Pacific, is that we gave Germany, Italy, and Japan their sovereignty back after all the death and destruction they caused. Used to be the winner would claim conquered nations/territories as their own.

America could have claimed Japan as a territory. America could have claimed Italy as a territory. If not for the Soviets taking East Germany, we could have claimed all of Germany as a territory. We sorta got West Germany, but gave control back to them. I'm sick of our good guy policies of giving beaten enemies their country back. AND THEN, AMERICAN TAX DOLLARS HELP TO REBUILD THESE WARRING NATIONS.

Pretty sure we did the same with Iraq and obviously Aftganiscrap to the Taliban of all people. If the USA is not going to benefit from the blood and treasure we spend on trying to expand liberty, I say no more and that includes the Ukraine. Let Russia have them. It's Europe's fight.

Hitler just piggybacked on Hindenburg.

If Hindenburg and Ludendorff had been executed after WW1, the Kaiser would have unified a peaceful Germany. Wilson was a wicked person who guaranteed WW2.

“Used to be the winner would claim conquered nations/territories as their own”...

which is exactly what the Soviets did with Poland, Romania etc. Imagine had they gotten a nuclear weapon first..GERMANOV...BELGUMNOV..ENGLANOV. They’d have went wild.

Wasn't it LeMay that was in charge of the fire bombing of Tokoyo? How many citizens did the fire bombings kill?

https://freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/3321714/posts#21

Here’s our old Homer_J_Simpson WW2 thread posted on 8/7/2015. Looks like some pertinent discussion.

I don't even accept that as a necessary condition at all. I have long said that it's impossible to have a rational discussion about the matter until sufficient time has passed that nobody is alive who even knows anyone who was involved in a potential invasion of Japan. You can't have an objective conversation when everything you read about it is so heavily personalized.

Year. And those “great military leaders” were not going to be the boots on the ground invading a kamikaze swarm of warriors including anthrax and plague fleas left on the invasion path.

WW1 and WW2 were both needless. So there.

Hope this helps.

From Doug Long’s website: The Decision the Atomic Bomb, http://www.doug-long.com/debate.htm

American Military Leaders Urge President Truman not to Drop the Atomic Bomb

The Joint Chiefs of Staff never formally studied the decision and never made an official recommendation to the President. Brief informal discussions may have occurred, but no record even of these exists. There is no record whatsoever of the usual extensive staff work and evaluation of alternative options by the Joint Chiefs, nor did the Chiefs ever claim to be involved. (See p. 322, Chapter 26)

In official internal military interviews, diaries and other private as well as public materials, literally every top U.S. military leader involved subsequently stated that the use of the bomb was not dictated by military necessity.

Navy Leaders

(Partial listing:

See Chapter 26 for an extended discussion)

In his memoirs Admiral William D. Leahy, the President’s Chief of Staff—and the top official who presided over meetings of both the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combined U.S.-U.K. Chiefs of Staff—minced few words:

[T]he use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. . . .

[I]n being the first to use it, we . . . adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children. (See p. 3, Introduction)

Privately, on June 18, 1945—almost a month before the Emperor’s July intervention to seek an end to the war and seven weeks before the atomic bomb was used—Leahy recorded in his diary:

It is my opinion at the present time that a surrender of Japan can be arranged with terms that can be accepted by Japan and that will make fully satisfactory provisions for America’s defense against future trans-Pacific aggression. (See p. 324, Chapter 26)

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet stated in a public address given at the Washington Monument on October 5, 1945:

The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace before the atomic age was announced to the world with the destruction of Hiroshima and before the Russian entry into the war. (See p. 329, Chapter 26) . . . [Nimitz also stated: “The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military standpoint, in the defeat of Japan. . . .”]

In a private 1946 letter to Walter Michels of the Association of Philadelphia Scientists, Nimitz observed that “the decision to employ the atomic bomb on Japanese cities was made on a level higher than that of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.” (See pp. 330-331, Chapter 26)

Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., Commander U.S. Third Fleet, stated publicly in 1946:

The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment. . . . It was a mistake to ever drop it. . . . [the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it. . . . It killed a lot of Japs, but the Japs had put out a lot of peace feelers through Russia long before. (See p. 331, Chapter 26)

Time-Life editor Henry R. Luce later recalled that during a May-June 1945 tour of the Pacific theater:

. . . I spent a morning at Cavite in the Philippines with Admiral Frank Wagner in front of huge maps. Admiral Wagner was in charge of air

search-and-patrol of all the East Asian seas and coasts. He showed me that in all those millions of square miles there was literally not a single target worth the powder to blow it up; there were only junks and mostly small ones at that.

Similarly, I dined one night with Admiral [Arthur] Radford [later Joint Chiefs Chairman, 1953-57] on the carrier Yorktown leading a task force from Ulithi to bomb Kyushu, the main southern island of Japan. Radford had invited me to be alone with him in a tiny room far up the superstructure of the Yorktown, where not a sound could be heard. Even so, it was in a whisper that he turned to me and said: “Luce, don’t you think the war is over?” My reply, of course, was that he should know better than I. For his part, all he could say was that the few little revetments and rural bridges that he might find to bomb in Kyushu wouldn’t begin to pay for the fuel he was burning on his task force. (See pp. 331-332, Chapter 26)

The Under-Secretary of the Navy, Ralph Bard, formally dissented from the Interim Committee’s recommendation to use the bomb against a city without warning. In a June 27, 1945 memorandum Bard declared:

Ever since I have been in touch with this program I have had a feeling that before the bomb is actually used against Japan that Japan should have some preliminary warning for say two or three days in advance of use. The position of the United States as a great humanitarian nation and the fair play attitude of our people generally is responsible in the main for this feeling.

During recent weeks I have also had the feeling very definitely that the Japanese government may be searching for some opportunity which they could use as a medium of surrender. Following the three-power conference emissaries from this country could contact representatives from Japan somewhere on the China Coast and make representations with regard to Russia’s position and at the same time give them some information regarding the proposed use of atomic power, together with whatever assurances the President might care to make with regard to the Emperor of Japan and the treatment of the Japanese nation following unconditional surrender. It seems quite possible to me that this presents

the opportunity which the Japanese are looking for.

I don’t see that we have anything in particular to lose in following such a program. The stakes are so tremendous that it is my opinion very real consideration should be given to some plan of this kind. I do not believe under present circumstances existing that there is anyone in the country whose evaluation of the chances of the success of such a program is worth a great deal. The only way to find out is to try it out. (See pp. 225-226, Chapter 18)

Rear Admiral L. Lewis Strauss, special assistant to the Secretary of the Navy from 1944 to 1945 (and later chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission), replaced Bard on the Interim Committee after he left government on July 1. Subsequently, Strauss repeatedly stated his belief that the use of the atomic bomb “was not necessary to bring the war to a successful conclusion. . . .” (See p. 332, Chapter 26) Strauss recalled:

I proposed to Secretary Forrestal at that time that the weapon should be demonstrated. . . . Primarily, it was because it was clear to a number of people, myself among them, that the war was very nearly over. The Japanese were nearly ready to capitulate. . . . My proposal to the Secretary was that the weapon should be demonstrated over some area accessible to the Japanese observers, and where its effects would be dramatic. I remember suggesting that a good place—satisfactory place for such a demonstration would be a large forest of cryptomaria [sic] trees not far from Tokyo. The cryptomaria tree is the Japanese version of our redwood. . . . I anticipated that a bomb detonated at a suitable height above such a forest . . . would [have] laid the trees out in windrows from the center of the explosion in all directions as though they had been matchsticks, and of course set them afire in the center. It seemed to me that a demonstration of this sort would prove to the Japanese that we could destroy any of their cities, their fortifications at will. . . . (See p. 333, Chapter 26)

In a private letter to Navy historian Robert G. Albion concerning a clearer assurance that the Emperor would not be displaced, Strauss observed:

This was omitted from the Potsdam declaration and as you are undoubtedly aware was the only reason why it was not immediately accepted by the Japanese who were beaten and knew it before the first atomic bomb was dropped. (See p. 393, Chapter 31)

In his “third person” autobiography (co-authored with Walter Muir Whitehill) the commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet and chief of Naval Operations, Ernest J. King, stated:

The President in giving his approval for these [atomic] attacks appeared to believe that many thousands of American troops would be killed in invading Japan, and in this he was entirely correct; but King felt, as he had pointed out many times, that the dilemma was an unnecessary one, for had we been willing to wait, the effective naval blockade would, in the course of time, have starved the Japanese into submission through lack of oil, rice, medicines, and other essential materials. (See p. 327, Chapter 26)

Private interview notes taken by Walter Whitehill summarize King’s feelings quite simply as: “I didn’t like the atom bomb or any part of it.” (See p. 329, Chapter 26; See also pp. 327-329)

As Japan faltered in July an effort was made by several top Navy officials—almost certainly including Secretary Forrestal himself—to end the war without using the atomic bomb. Forrestal made a special trip to Potsdam to discuss the issue and was involved in the Atlantic Charter broadcast. Many other top Admirals criticized the bombing both privately and publicly. (Forrestal, see pp. 390-392, Chapter 31; p. 398, Chapter 31) (Strauss, see p. 333, Chapter 26; pp. 393-394, Chapter 31) (Bard, see pp. 225-227, Chapter 18; pp. 390-391, Chapter 31)

Air Force Leaders

(Partial listing:

See Chapter 27 for an extended discussion)

The commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces, Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, gave a strong indication of his views in a public statement only eleven days after Hiroshima was attacked. Asked on August 17 by a New York Times reporter whether the atomic bomb caused Japan to surrender, Arnold said:

The Japanese position was hopeless even before the first atomic bomb fell, because the Japanese had lost control of their own air. (See p. 334, Chapter 27)

In his 1949 memoirs Arnold observed that “it always appeared to us that, atomic bomb or no atomic bomb, the Japanese were already on the verge of collapse.” (See p. 334, Chapter 27)

Arnold’s deputy, Lieutenant General Ira C. Eaker, summed up his understanding this way in an internal military history interview:

Arnold’s view was that it [the dropping of the atomic bomb] was unnecessary. He said that he knew the Japanese wanted peace. There were political implications in the decision and Arnold did not feel it was the military’s job to question it. (See p. 335, Chapter 27)

Eaker reported that Arnold told him:

When the question comes up of whether we use the atomic bomb or not, my view is that the Air Force will not oppose the use of the bomb, and they will deliver it effectively if the Commander in Chief decides to use it. But it is not necessary to use it in order to conquer the Japanese without the necessity of a land invasion. (See p. 335, Chapter 27)

[Eaker also recalled: “That was the representation I made when I accompanied General Marshall up to the White House” for a discussion with Truman on June 18, 1945.]

On September 20, 1945 the famous “hawk” who commanded the Twenty-First Bomber Command, Major General Curtis E. LeMay (as

reported in The New York Herald Tribune) publicly:

said flatly at one press conference that the atomic bomb “had nothing to do with the end of the war.” He said the war would have been over in two weeks without the use of the atomic bomb or the Russian entry into the war. (See p. 336, Chapter 27)

The text of the press conference provides these details:

LeMay: The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb.

The Press: You mean that, sir? Without the Russians and the atomic bomb?

. . .

LeMay: The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.

(See p. 336, Chapter 27)

On other occasions in internal histories and elsewhere LeMay gave even shorter estimates of how long the war might have lasted (e.g., “a few days”). (See pp. 336-341, Chapter 27)

Personally dictated notes found in the recently opened papers of former Ambassador to the Soviet Union Averell Harriman describe a private 1965 dinner with General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, who in July 1945 commanded the U.S. Army Strategic Air Force (USASTAF) and was subsequently chief of staff of U.S. Air Forces. Also with them at dinner was Spaatz’s one-time deputy commanding general at USASTAF, Frederick L. Anderson. Harriman privately noted:

Both men . . . felt Japan would surrender without use of the bomb, and neither knew why the second bomb was used. (See p. 337, Chapter 27)

Harriman’s notes also recall his own understanding:

I know this attitude is correctly described, because I had it from the Air Force when I was in Washington in April ‘45. (See p. 337, Chapter 27)

In an official 1962 interview Spaatz stated that he had directly challenged the Nagasaki bombing:

I thought that if we were going to drop the atomic bomb, drop it on the outskirts—say in Tokyo Bay—so that the effects would not be as devastating to the city and the people. I made this suggestion over the phone between the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and I was told to go ahead with our targets. (See p. 345, Chapter 27)

Spaatz insisted on receiving written orders before going forward with the atomic bombings in 1945. Subsequently, Lieutenant General Thomas Handy, Marshall’s deputy chief of staff, recalled:

Well, Tooey Spaatz came in . . . he said, “They tell me I am supposed to go out there and blow off the whole south end of the Japanese Islands. I’ve heard a lot about this thing, but my God, I haven’t had a piece of paper yet and I think I need a piece of paper.” “Well,” I said, “I agree with you, Tooey. I think you do,” and I said, “I guess I’m the fall guy to give it to you.” (pp. 344-345, Chapter 27)

In 1962 Spaatz himself recalled that he gave “notification that I would not drop an atomic bomb on verbal orders—they had to be written—and this was accomplished.” (p. 345, Chapter 27)

Spaatz also stated that

The dropping of the atomic bomb was done by a military man under military orders. We’re supposed to carry out orders and not question them. (See p. 345, Chapter 27)

In a 1965 Air Force oral history interview Spaatz stressed: “That was purely a political decision, wasn’t a military decision. The military man carries out the order of his political bosses.” (See p. 345, Chapter 27)

Air Force General Claire Chennault, the founder of the American Volunteer Group (the famed “Flying Tigers”)—and Army Air Forces commander in China—was even more blunt: A few days after Hiroshima was bombed The New York Times reported Chennault’s view that:

Russia’s entry into the Japanese war was the decisive factor in speeding its end and would have been so even if no atomic bombs had been dropped. . . . (See pp. 335-336, Chapter 27)

Army Leaders

(Partial listing:

See Chapter 28 for an extended discussion)

On the 40th Anniversary of the bombing former President Richard M. Nixon reported that:

[General Douglas] MacArthur once spoke to me very eloquently about it, pacing the floor of his apartment in the Waldorf. He thought it a tragedy that the Bomb was ever exploded. MacArthur believed that the same restrictions ought to apply to atomic weapons as to conventional weapons, that the military objective should always be limited damage to noncombatants. . . . MacArthur, you see, was a soldier. He believed in using force only against military targets, and that is why the nuclear thing turned him off. . . . (See p. 352, Chapter 28)

The day after Hiroshima was bombed MacArthur’s pilot, Weldon E. Rhoades, noted in his diary:

General MacArthur definitely is appalled and depressed by this Frankenstein monster [the bomb]. I had a long talk with him today, necessitated by the impending trip to Okinawa. . . . (See p. 350, Chapter 28)

Former President Herbert Hoover met with MacArthur alone for several

hours on a tour of the Pacific in early May 1946. His diary states:

I told MacArthur of my memorandum of mid-May 1945 to Truman, that peace could be had with Japan by which our major objectives would be accomplished. MacArthur said that was correct and that we would have avoided all of the losses, the Atomic bomb, and the entry of Russia into Manchuria. (See pp. 350-351, Chapter 28)

Saturday Review of Literature editor Norman Cousins also later reported that MacArthur told him he saw no military justification for using the atomic bomb, and that “The war might have ended weeks earlier, he said, if the United States had agreed, as it later did anyway, to the retention of the institution of the emperor.” (See p. 351, Chapter 28)

In an article reprinted in 1947 by Reader’s Digest, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers (in charge of psychological warfare on MacArthur’s wartime staff and subsequently MacArthur’s military secretary in Tokyo) stated:

Obviously . . . the atomic bomb neither induced the Emperor’s decision to surrender nor had any effect on the ultimate outcome of the war.” (See p. 352, Chapter 28)

Colonel Charles “Tick” Bonesteel, 1945 chief of the War Department Operations Division Policy Section, subsequently recalled in a military history interview: “[T]he poor damn Japanese were putting feelers out by the ton so to speak, through Russia. . . .” (See p. 359, Chapter 28)

Brigadier Gen. Carter W. Clarke, the officer in charge of preparing MAGIC intercepted cable summaries in 1945, stated in a 1959 interview:

we brought them [the Japanese] down to an abject surrender through the

accelerated sinking of their merchant marine and hunger alone, and when we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew that we knew we didn’t need to do it, we used them as an experiment for two atomic bombs. (See p. 359, Chapter 28)

In a 1985 letter recalling the views of Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, former Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy elaborated on an incident that was

very vivid in my mind. . . . I can recall as if it were yesterday, [Marshall’s] insistence to me that whether we should drop an atomic bomb on Japan was a matter for the President to decide, not the Chief of Staff since it was not a military question . . . the question of whether we should drop this new bomb on Japan, in his judgment, involved such imponderable considerations as to remove it from the field of a military decision. (See p. 364, Chapter 28)

In a separate memorandum written the same year McCloy recalled: “General Marshall was right when he said you must not ask me to declare that a surprise nuclear attack on Japan is a military necessity. It is not a military problem.” (See p. 364, Chapter 28)

In addition:

- On May 29, 1945 Marshall joined with Secretaries Stimson and Forrestal in approving Acting Secretary of State Joseph C. Grew’s proposal that the unconditional surrender language be clarified (but, with Stimson, proposed a brief delay). (See pp. 53-54, Chapter 4)

- On June 9, 1945, along with the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Marshall recommended that a statement clarifying the surrender terms be issued on the fall of Okinawa (June 21). (See pp. 55-57, Chapter 4)

- On July 16, 1945 at Potsdam—again along with the other members of

the Joint Chiefs —Marshall urged the British Chiefs of Staff to ask Churchill to approach Truman about clarifying the terms. (See pp. 245-246, Chapter 19)

- On July 18, 1945, Marshall led the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in directly urging the president to include language in the Potsdam Proclamation allowing Japan to choose its own form of government. (See pp. 299-300, Chapter 23)

In his memoirs President Dwight D. Eisenhower reports the following reaction when Secretary of War Stimson informed him the atomic bomb would be used:

During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. . . . (See p. 4, Introduction)

Eisenhower made similar private and public statements on numerous occasions. For instance, in a 1963 interview he said simply: “. . . it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.” (See pp. 352-358, Chapter 28)

That argument cuts both ways, IMO.

You and I were not on in the military in the Pacific at that time (I presume). But my father was, and as my post at #108 with my father’s image illustrates, he had very strong opinions on this. As did hundreds of thousands of other men, and millions of family members.

Just going to ask the question-did you actually view Bill Whittle’s video on this?

He discusses in great detail EXACTLY why the assumptions that the Japanese people would fight to the bitter end were not based on some kind of American government or military upper command announcement that said they would.

He references SPECIFIC policy statements made by Hirohito, and senior military officers who were responsible for the policies that would be implemented when an invasion would occur. This is completely separate from some politician in Washington saying “Oh, they would fight to the end and cause tens or hundreds of thousands of casualties, so we spared our own men by dropping the bomb”...

This analysis was based on hard fact, obtained by bloody experience going from island to island, the death toll and casualty tolls increasing the closer we got to mainland Japan, and the people in charge, the people responsible for making it happen, the people responsible for shooting or hanging anyone who refused to take part made definitive, clear statements about what they had in store.

Not that anyone needed to be convinced after seeing the actions of civilians deliberately destroying themselves in Saipan and Okinawa because of both fear, and the desire to fulfill the will of the Emperor.

I honestly don’t think I or anyone else is going to convince you otherwise. You have your opinion and do not seem in any way inclined to change it based on much of anything. And I will respect your personal opinion which you feel has validity.

As I expect you to respect mine, which I feel has validity.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.