Neither geological nor climatological but rather sociological in characterThanks Nikas777.

|

||

| · join · view topics · view or post blog · bookmark · post new topic · subscribe · | ||

Posted on 09/28/2009 9:26:36 AM PDT by Nikas777

“The Catastrophe” - Part 1: What the End of Bronze-Age Civilization Means for Modern Times

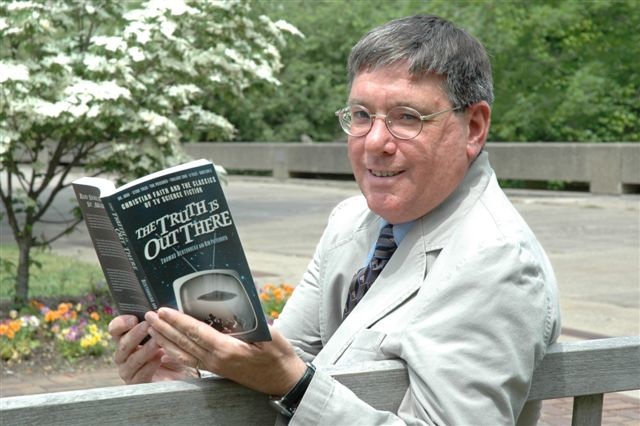

From the desk of Thomas F. Bertonneau on Tue, 2009-09-15 09:20

Introduction to Part I: Modern people assume the immunity of their situation to major disturbance or – even more unthinkable – to terminal wreckage. The continuance of a society or culture depends, in part, on that very assumption because without it no one would complete his daily round. A man cannot enthusiastically arise from bed as the sun comes up and set about the day’s errands believing that all undertakings will issue vainly because the established order threatens to go up in smoke before twilight. Just as it serves this necessity, however, the assumption of social permanence, that tomorrow will necessarily be just like today, can, when it becomes too habitual through lack of reflection, lead to dangerous complacency.

It is healthy, therefore, to think in an informed way about the possibility that our society might break down completely and become unrecognizable. Such things are more than mere possibility – they have happened. Societies – and, it is fair to say, whole standing civilizations – have disintegrated swiftly, leaving behind them depopulation and material poverty. In the two parts of the present essay, I wish to look into one of the best documented of these epochal events, one that brought abrupt death and destruction to a host of thriving societies, none of which survived the scourge. I have divided my essay into two parts, each part further divided into four subsections.

I. Archeologists, historians, and classicists call it “the Catastrophe.” It happened more than three thousand years ago in the lands surrounding the Eastern Mediterranean. Neither geological nor climatological but rather sociological in character, this chaotic enormity erased civilization in a wide swath of geography stretching from the western portions of Greece east to the inner fastnesses of Anatolia, and all the way to Mesopotamia; it turned south as well, overrunning many islands, finally swamping the borders of Egypt. It left cities in smoking ruin, their wealth plundered; it plunged the affected regions into a Dark Age, bereft of literacy, during which populations drastically shrank while the level of material culture reverted to that of a Stone Age village. Echoes of the event – or complicated network of linked events – turn up in myth and find reflection in early Greek literature. The Trojan War appears to be implicated in this event, as do certain episodes of the Old Testament. Recovered records hint at this massive upheaval: diplomatic letters dictated by Hittite kings and tablets bearing military orders from the last days of the Mycenaean palace-citadels. Places like Sicily and Sardinia took their names in the direct aftermath of the Catastrophe.

A distant but still piquant awareness of the Catastrophe’s effects inspired one of the earliest theories of history. In his Works and Days, mostly consisting of common sense advice to the humble peasant farmers of Boeotia, the Eighth Century B.C. Greek poet Hesiod declared that humanity could count five phases. The first three belong clearly to myth, but the fourth and the fifth boast a more realistic or historical character in the poet’s description. The fourth men, Hesiod says, generated the heroes whose deeds the riveting lays of the Trojan War enshrine, but the war itself amounted to the last, lusty cry of a warrior caste that, while pouring blood and treasure into a ten-year siege, ignored sinister developments back home. The prolonged absence of the baron-kings in their enterprise of glory led to a domestic power vacuum. The Greek adventurers would pay dearly for the costly vanity of their Asian victory. In Hugh Evelyn-White’s translation of Hesiod: “Grim war and dread battle destroyed a part of [the heroes], some in the land of Cadmus at seven-gated Thebes when they fought for the flocks of Oedipus, and some, when it had brought them in ships over the great sea gulf to Troy for rich-haired Helen’s sake: there death’s end enshrouded a part of them.”

Homer’s Odyssey, which precedes Works and Days by a generation, gives another hint of the debacle through its constant invocation of Agamemnon’s fate when he returned from Troy to Mycenae and by its main storyline of the squatters in Odysseus’ palace who have taken advantage of the king’s absence to make a blatant attempt on his kingdom. The legend of Idomeneus hints at similar troubles in Crete. In light of the Catastrophe, Homer’s emphasis on the gluttony and loutish behavior of the suitors acquires a provocative meaning. The suitors resemble Hesiod’s fifth men, the phase of humanity to which Hesiod sees himself as belonging: this is the age inaugurated by the “race of iron.” Envy or resentment, disregard for law and civilized achievement, and a strong proclivity to violent expropriation of other men’s chattels constitute the chief traits of the Hesiodic “Iron Age.”

Hesiod says that the successors to the heroes brought forth a degraded way of life inherently violent and unjust, so much so that in a prophecy he foresees divine retribution:

Zeus will destroy this race of mortal men also when they come to have grey hair on the temples at their birth. [Neither will] the father… agree with his children, nor the children with their father, nor guest with his host, nor comrade with comrade; nor will brother be dear to brother as aforetime… They will not repay their aged parents the cost of their nurture, for might shall be their right: and one man will sack another’s city… The wicked will hurt the worthy man, speaking false words against him, and will swear an oath upon them.

Homer’s suitors resemble the Hesiodic savages closely, being oath-breakers, flouters of custom, and plotters of assassination, who scheme with criminal invidiousness to appropriate Odysseus’ wealth and royal authority for their own. Homer, of course, identifies the suitors not as invaders who have come to Ithaca with a piratical intention but rather as spoiled sons of local aristocrats, thwarted at home in their ambitions, who constitute a kind of insurgency. The suitors seek illegitimate upward mobility in the presumptive widowhood of Penelope and the patent inexperience of Telemachus.

Homer makes it abundantly, thematically clear that the suitors despise orderly existence, labeling them with the same pejorative formulas that he applies to the inarguably primitive Cyclopes, who are actual cave dwellers. The disintegration of the heroic polities all across the Greek world is what provides the often-invoked backdrop of Odysseus’ adventures. The fate of Troy at the hands of the Achaean expedition foretells the fate of many a heroic kingdom on its monarch’s return. Homer thus grasps acutely that he lives in a time of providential revival. Homer knows that between his own brightening day and the last sunlit era stretches a prolonged twilight commencing with abrupt destruction and consisting in fallow centuries. The heroic sagas follow the generations far enough to say that Orestes avenged the death of Agamemnon and that Odysseus quelled the insurrection in his palace, but after that they fall silent. No contemporary of Homer tells us about the reign of Telemachus or that of Nestor’s eldest son. Apollodorus does record, at a late date, a story that after the events in Odyssey foreigners indeed descended on Ithaca and drove Odysseus into exile.

II. Hesiod’s characterization of the fifth men as a race of “iron,” the emblematic metal of moral degradation, signifies a good deal. In his metallic succession of ages, the poet had identified the heroes with the metal bronze. Archeologists have long spoken of the phase of civilization, from about 2000 B.C. down to 1100 B.C., as the Bronze Age, on account of its primary metallurgical achievement. The Bronze-Age polities were also the first literate societies, not in a sense of general literacy, but rather of administrative literacy. The mastery of elaborate syllabary writing systems by royal bureaucracies made possible for the first time in history the organization of complex principalities and even empires, while the bureaucratic character of such regimes perhaps also limited their adaptability in emergent conditions. As Robert Drews points out in his masterly End of the Bronze Age (1993), a providential access to iron weaponry endowed on “uncivilized populations that until that time had been no cause for concern to the cities and kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean” a capacity for “a new style of warfare” that the existing societies never anticipated and could not rally themselves to meet.

Rapidly moving foot soldiery armed with novel iron swords broke the back of aristocratic chariot-and-archery armies on every occasion. The tempest of plundering and burning commenced in the northern areas of Greece, with raids on the tempting granaries and treasuries of the palace-citadels, around the time that the heroes of Troy undertook to wend their way home. Drews, correlating the mass of evidence and the many interpretations, writes, “the Catastrophe seems to have begun with sporadic destructions in the last quarter of the thirteenth century [B.C.], gathered momentum in the 1190s, and raged in full fury in the 1180s.” In its whirlwind celerity as well as in its incendiary result, Drews reckons the Catastrophe as “arguably the worst disaster in ancient history, even more calamitous than the collapse of the western Roman Empire.”

One glimpses the urgency of those remote and foreign days in the “Linear B” tablets recovered from the burnt remains of the Mycenaean palace – identified by archeologists not without cause as “Nestor’s Palace” – at Pylos on the west coast of the Peloponnese in the Messenia district. In Odyssey, Homer records how Telemachus visited Pylos in search of intelligence about his long-absent father. For Homer, Nestor’s city represents the ideal of an intact heroic society, at peace with itself, aware of no external threat, its common people reconciled to the ruler by his justice and generosity. Pylos, unlike Mycenae, lacked fortifications. The obvious inference is that its builders and occupiers never thought it needed any.

Drews argues that whatever the vices of the Bronze Age societies, whether Greek or Levantine or Anatolian, they all give abundant evidence of working in proper order until the last days although there are signs of alarm here and there in the record. For example, in the final decade of the Thirteenth Century B.C. or in the initial decade of the Twelfth, someone – we might guess at a consortium of Peloponnesian principalities, with Pylos or perhaps Mycenae taking the lead – undertook construction of an ambitious defensive wall across the Isthmus of Corinth. The builders of this Achaean equivalent of Hadrian’s Wall can only have embarked on the project hastily when they saw an imminent, potentially lethal menace developing rapidly to the north. The wall, incomplete, failed its purpose.

At Pylos, shortly before the enemy sacked and burned the city, the king through his lieutenants busied himself in issuing abrupt and desperate orders to his field officers. We know this because the scribes wrote these orders on clay tablets for later copying in a more “permanent” medium, such as papyrus or vellum. Ordinarily, the janitor threw out the clay tablets. The conflagration, however, destroyed the “permanent” records and providentially baked the raw clay into a form that burial beneath the rubble then fortuitously preserved. It is a snapshot of the end.

The best account of these military orders, as issued in a distraught hour by desperate men, comes from Leonard Palmer’s invaluable Minoans and Mycenaeans, published more than forty-five years ago. Palmer considered the geography implied by the tablets, which direct military commanders to send soldiers and weapon-makers hurriedly to different locations. Palmer came to the conclusion that the leaders of Pylos expected attacks from the north, primarily along the shoreline – and therefore from a ship borne, Viking-like raid – but also over various inland routes. The enemy must have been numerous and mobile. The Cretan writing system used by the Mycenaean scribes ill fitted the Greek language, so Palmer, like every other decipherer of “Linear B,” whether in the case of the Pylos tablets or others, must tease out much by guesswork. Nevertheless, Palmer can actually identify by name at least two of the line officers, Echelawon and Lawagetas, whom the inscriptions indicate as commanders of the coastal and border guards.

Like Crockett and Bouwie at the Alamo, Echelawon and Lawagetas were doomed heroes. As the crisis loomed, headquarters exerted itself to send additional oarsmen to a naval station on the Gulf of Messenia. The defenders, as Palmer reports, were sufficiently desperate to have ordered votive statuettes of Potnia or “the Mistress” to be removed from temples and melted down to make weapons. The Pylians much revered this Mycenaean goddess antecedent to Athene. In Odyssey, Athene figures as the hero’s divine patroness. She fights beside Odysseus and Telemachus in their battle against the suitors. Metaphorically Potnia was fighting beside Echelawon and Lawagetas at Messenia and at the unfinished wall.

It did not go as well in Pylos a generation after the heroic returns as it went for Odysseus in his time. The commanders of the Pylian defense ordered the hasty transfer of soldiers described as “willing to row” from army to navy postings. To the “farther provinces” went the foundry workers whose job it would have been to melt down the images of Potnia for the casting of arrowheads and javelin points. “Masons” accompanied these smiths. One immediately thinks of fortifications in need of bolstering or defensive walls in need of repair. The tablets also make reference to women who work as “grain pourers.” These had been convened en masse in Pylos itself and at Leuktra, a northerly regional settlement, where they undoubtedly helped to prepare field-rations for the line. “The overall picture of emergency… is unmistakable,” Palmer writes; “the archive is permeated with this sense emergency.” Palmer concludes: “Thus alerted and organized, the Pylians awaited the attack from the sea. The ruin of the palace and the fire that preserved the archives are eloquent testimony that the attack was successful. Pylos was blotted from the face of the earth and its site was never again occupied by human habitations.”

III. “One man will sack another’s city.” So wrote Hesiod. In a chapter of The End of the Bronze Age entitled “The Catastrophe Surveyed,” Drews systematically tallies up the wave of early Twelfth-Century incendiary activity in Anatolia, Cyprus, Syria, the Southern Levant, Greece, the Aegean, and Crete. Borrowing a phrase from the German scholar Kurt Bittel, Drews remarks that, “at every Anatolian site known to have been important in the Late Bronze Age” one finds a “destruction level” significant of a universal “Brandkatastrophe.” Thanks to Homer, posterity remembered the Mycenaeans although for a long time intellectual opinion considered the events of Iliad and Odyssey to be pure fancy. In the absence of a Homer, however, the Anatolian victims of the Catastrophe vanished from memory. The Hittites ran a formidable empire with monumental cities for three hundred years and were perhaps the greatest diplomatists of their age, but in classical times no one remembered them; they emerged from millennia of oblivion only through the efforts of archeology in the first half of the Twentieth Century.

Hattusas, the capital city of the Hittite Empire, went up in flames shortly after the destruction of Troy VI, which the Hittites knew under a double name as the kingdom of Taruisa-Wilusa (Troy-Ilios). The last effective Hittite king, Suppiluliumas II, had actually helped his Syrian and Cypriote allies vanquish a pirate flotilla, with its embarked marine soldiery, near Cyprus, swiftly raising his own navy for the purpose. This sea battle signified the military last hurrah of the once formidable Hittite empire. With his northern trade routes already cut by the disaster at Troy and his attention drawn to the south, Suppiluliumas could not overcome powerful pressure from an age-old barbarian enemy, the Gasga or Kaskians. It was not only Hattusas that collapsed amidst fire and smoke, as Drews says, but also the cities at Alaka Höyük, Alishar, Maşat Höyük, and Karaoglan, whose old names vanished with their inhabitants so that we must nowadays identify them by the nomenclature of Turkish geography. Milawanda (classical Miletus), where Achaean colonists maintained a trading polity under Hittite license, also perished in the general rout.

The architects of the Cypriote cities built according to a sophisticated aesthetic, influenced by the old Cretan civilization. These exquisite towns met their death at just about the same time as the Anatolian cities met theirs. At one Cypriote site, the fleeing citizens hid their valuables in cubbyholes, imagining that they might soon return. Cyprus, like Attica, evidences a modicum of cultural continuity in the aftermath of the Catastrophe. The new style compares with the old, however, in an impoverished way. The people resettle not so much in the old places as in difficult-to-reach mountain fastnesses. The new architecture is – defensive. Refugees from the Peloponnese certainly arrived in Cyprus following the destruction in their homeland. A form of “Linear B,” the Eteo-Cypriote Syllabary, remained in use among the Cypriote Greeks, who spoke an Achaean-derived Ionian dialect, well into historical times.

In the Levant, the best-attested site of the Catastrophe is ancient Ugarit (now Ras Shamra in Syria), a wealthy and culturally sophisticated Bronze Age city, with an attendant petty empire. Ugarit derived its prosperity from its middleman position in the Eastern Mediterranean trading economy; the kingdom could make war but it preferred to make treaties of exchange. As at Pylos, the onslaught accidentally preserved written documentation of the final panic. In Drews’ words, “when Ugarit was destroyed some hundred tablets were being baked in the oven, and so we have documents written on the very eve of its destruction.” Hammurapi, the Ugaritic king, reported on the news to his ally the king of Alashia (Cyprus). His words register his sense of shock and helplessness: “Behold, the enemy’s ships came (here); my cities (?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country.” Manuel Robbins, in his Collapse of the Bronze Age (2001), quotes Hammurapi’s letter of appeal to the Hittite king, not yet driven down but already in dire straits on his own. Says Ugarit: “The enemy advances against me and there is no number… our number is… send whatever is available, look to it and send it to me.”

The phrase “no number” means numberless or innumerable. The image of a multitudinous swarm or horde represents the Catastrophe essentially. But the Hittite king – it might be Suppiluliumas II although it might also be Arnuwanda, his obscure successor – had already written to Hammurapi requesting grain by urgent transport to offset the effects of a devastating famine. This food shortage might have stemmed from tentative depredations in the northern provinces of Hatti (the Hittites’ name for their country), or social collapse driven by crop-failure might have signaled to a piratical conscience that plundering raids could safely commence. “Look, lads – the guard is down,” as some cunning brigand might have said. With Hatti already embroiled, no aid came. Ugarit died. A large number of arrowheads excavated from its ruins suggest to Robbins a systematic slaughter of those inhabitants who could not escape. In addition to Ugarit, the cities of Alalakh, Hamath, Qatna, and Qadesh also fell to “the hordes” (Hammurapi’s phrase) that launched themselves on the Levant.

IV. In the east, Assyria proved a bulwark against the tide. In the south, Egypt likewise held out, in its qualified way. Pharaoh Ramesses III erected stelae celebrating his victory over “the Sea Peoples” who poured into the Nile delta in the 1180s. Yet as Drews and Robbins and many other commentators have pointed out, the defeat of the invaders, while it prevented the destruction of the New Kingdom, portended the stultification of Egyptian culture and the end of Egypt’s role as an international power. From the Eleventh Century B.C. onwards the Pharaohs largely minded their own business until first the Persians and then the Macedonians incorporated them. That aside, the victory stelae provide useful information about the identity of the mischief-makers. Among the identifiable ethnic components of this marauding conglomerate, the Egyptian scribes listed (following Drews’ summary) Ekwesh, Denyen, Lukka, Shardana, Shekelesh, Tjekker, Tursha, and Weshesh. According to the scribes, these mixed peoples came from “the islands” or “the coastal lands.”

Some of these names retain meaning for modern researchers. The Ekwesh and Denyen, for example, are probably Achaeans and Danaans – that is Greeks, dubbing themselves, as they do in Homer. The Lukka are Lycians, an Anatolian people who lived more or less at peace with the Hittites as allies or vassals; they were still a nation in classical times. The Shardana, Shekelesh, and Tursha adorn the roster somewhat unexpectedly. The first two names have connections with Sardinia and Sicily, but the evidence cannot tell us whether they came from those places bearing the name of their origin or went on to them subsequently to christen them. The Tursha are the Tyrrhenians or Etruscans, a people associated with Italy. Again, it remains unclear whether they came from Italy or went on to that place. The Tjekker are hill tribes from the Levantine interior. The name Weshesh might be a variant, hence also a duplicate, of Ekwesh. Why are these exotic philological matters important?

These items of linguistic esoterica warrant attention because they bring up the problem of catastrophic agency. Archeologists and historians have known about the Catastrophe for a century although their sense of it has become more acute in the last fifty years. Several theories have arisen to explain the near-universality of the Catastrophe in its region. The earliest and in some ways the most tenacious is the Migration Theory. This theory posits that a single ethnically uniform people, reaching a point of crowded numbers in their Balkan homeland and arming themselves with novel iron swords, poured into Greece and then into the Aegean; they would also have crossed the Bosporus into Asia Minor where they continued their rampage, driving all before them. In a kind of domino process, they displaced others, some of whom joined them in the train of rapine and arson until the madness spent itself in Egyptian sands. Various minor sequelae to this Völkerwanderung account for the redistribution of old nationalities, the disappearance of others, and the appearance of novel nationalities that differentiate one end of the catastrophic epoch from the other.

Introduction to Part II: In Part I of this essay, I began by reminding readers of the necessary complacency that accompanies civilized life. Civilized people go about their lives on the dual assumption of institutional permanency and a continuity of custom. The assumption that plans made today will see their fruition tomorrow belongs to the background of organized existence and contributes to motivating our purposive behavior. The same assumption can lapse into complacency, however, so that, even as signs of trouble emerge on the horizon, a certain denial disarms people from responding to looming disruption with sufficient swiftness and clarity. People take civilization for granted; they rarely contemplate that it might come tumbling down about their ears. Insofar as the historical record has something important to teach ordinary people who are not specialists in the subject, it might well be the lesson that all known societies before the modern society have come to an end. Some of them have come to an end abruptly and violently.

One such society, or civilization, was the Bronze Age civilization of the Twelfth Century B.C. in the Eastern Mediterranean. The singular term “civilization,” rather than the plural, is appropriate even though the geographical-cultural region of the Eastern Mediterranean contained many separate peoples distinguished by their distinctive languages, religious beliefs, and customs. These societies – Greek, Semitic, Western Anatolian, and Pelagic – were in commercial, diplomatic, and artistic communication with one another. They together constituted a pattern of civilized life, whose individual element-nations all had the same stake in maintaining the coherency of the whole. As was Part I, Part II is divided in four subsections.

I. The preponderance of archeological and epigraphic evidence coupled with the testimony of legend and epic narrative would attribute the Catastrophe to a wave of barbarian depredation. This does not mean that other factors played no role. Competing theories about the Catastrophe, as summarized by Robert Drews in The End of the Bronze Age, postulate Systemic Breakdown or Natural Disaster, such as drought or earthquake, as accounting for the abrupt collapse of so many nations, somewhere between 1200 and 1180 B.C. Drews discounts both as likely sole causes, but suggests that Systemic Breakdown in response to a crop-failure or an outbreak of disease might have eroded the stability of the existing societies. The Bronze Age kingdoms were inflexibly organized, heavily ritualistic in their conception of life, and on occasion testily feudal in their relations with one another, as the episode of Paris and Helen makes clear. Widespread drought leading to famine and disease, which the records of Hatti attest, might well have created a social crisis, with a cascading effect, with which administrative inflexibility could not cope. Yet as Drews emphasizes, despite their cumbersomeness, the Bronze Age kingdoms apparently functioned as usual right up to the hour of their sudden demise.

Drews rejects the single-people version of the Migration Theory, still entertained by some, but he retains certain elements of the same general idea. There is little practical difference, after all, between a monoglot swarm of buccaneers and a polyglot congeries of predatory peoples, all operating according to the same near-term opportunism. Manuel Robbins stresses the importance of drought and famine in fueling the violence but like Drews sees the commotion of peoples, rather than the movement of one people, as essential to understanding the violence of the phenomenon. Drews’ interpretation is interesting because it implies – even if it never explicitly states – that there was something mimetic or imitative in the rapidly successive separate chapters of the Catastrophe; his idea furthermore possesses the charm that literary echoes of the event, such as those in Homer and Hesiod, acquire added explanatory value in light of it. If not in Drews or Robbins or other modern sources, then in observations by the archaic poets we might actually be able to discover the motivation of the Catastrophe.

The Catastrophe begins, as Drews sees it, with the descent of a people called the Dorians into Greece. The Dorians, a culturally primitive Greek-speaking tribe (or plurality of tribes), lived in the mountainous North of the Helladic peninsula and in adjacent regions of the southern Balkans. Greek legend speaks of the violent “Return of the Heraclidae” following the conclusion of the Trojan War. The “Return of the Heraclidae” – that is, the Dorians – plunged the heroic world into terminal chaos.

The Dorians staged the murderous, incendiary assault on Pylos. Their rapacious kinsmen had already pillaged and burned the palace-citadels at Gla, Mycenae, Orchomenos, Sparta, Thebes, Tiryns, and dozens of other sites, big and small. (See map) Some of these, like Mycenae, were heavily fortified, suggesting that the attackers were numerous and ferocious. When Hellas emerged from the four centuries of its Dark Age, the Hellenes remained culturally divided between the descendants of the Mycenaeans and the descendants of their destroyers. The Attic-Ionian civilization, literate, political, and mercantile stood against Doric culture, exemplified by the Spartans, who remained locked in the warrior-society ruthlessness that had made their barbaric ancestors such formidable final enemies of the Achaean Greeks. As Drews mentions, the Peloponnesian Wars in many ways merely resumed an old conflict in the Greek world going back to the end of the Bronze Age.

The holocaust in the Peloponnese made prodigious mayhem but at last fell shy of the absolute. Pockets of resistance put up a fight, forcing the invaders to bypass them. This happened in Iolkos in Thessaly and more importantly in Attica. The Athenians always maintained that their history on the site was undisrupted from heroic times. So it seems, on the material as well as on the folkloric evidence. So also does it seem that refugees from the turmoil elsewhere in Greece saw Attica as an initial destination for displaced persons. One Attic legend speaks of Neleius, a refugee from Pylos, no less, who organized resistance against brigands. From Attica, displaced persons embarked for Cyprus, Rhodes, and the coastal areas of Anatolia after the violence had worked itself through. A variant of Linear B, the Mycenaean script, appears in Cyprus where it remains in use down to the Hellenistic period.

In this way the Ionians gradually resettled in parts of Greece beyond Attica, extending their sense of enlightened order well beyond their home base – in particular to the coastal areas of what is today Turkey. The Ionians, unlike the Dorians, discarded many of the institutions of the Bronze Age, most especially kingship, but also the habit of the fortified city. Where kingship remained in the Ionic world, it persisted only as a ritualistic vestige. The new dispensation in Ionia inclined to the democratic. Doric institutions, as at Sparta or in Crete, remained tribal and hidebound. Spartan hegemony in Laconia gives some idea of the original Doric attitude to the conquered – utter dominating bigotry and, in practice, enslavement or Helotism. Originally it would have been contempt sprung from envy: the envy of the savage who sees across the borders into the ease and luxury of a more highly developed way of life and schemes how he might profit by the labor of others.

Homer’s suitors, despite the poet’s presentation of them as natives of Ithaca, exhibit just this resentful attitude. The pampered sons of local aristocracy, they can boast no accomplishments of their own. They produce nothing while they consume the produce of others. Resenting Telemachus, the heir apparent in Ithaca, they see cynically in Penelope the chance for dynastic marriage and wealth-by-dowry. The name of their leader, Antinous, means “He who defies Reason” or more simply “He of the Disordered Mind.”

It is possible that the Greek chapter of the Catastrophe combined external encroachment by treasure-hungry savages with internal divisions and treachery in the feudal kingdoms. One can imagine Mycenaean betrayers offering their expertise in organization to the restless Dorians or trading simple access to the city for the privilege of participating in the sack and so either way exacerbating the troubles. “For a share of the takings and safe passage, a certain gate will be left unguarded.” It would have been something like that.

Beyond this theorizing lies another, perhaps more important point. The Bronze-Age kingdoms constituted an ecumene: All of them communicated with one another regularly, all traded with one another, and all exchanged intelligence along with goods via the trade-routes. A coherent world, this network of mercantile polities permitted and encouraged the dissemination of intelligence. With the channels still open news of the disaster in Greece would have crossed the Bosporus in short order. It would have filtered from the cities into the hinterlands. It would have provided an example, a set of cues: The cities are vulnerable; a mass of skirmishers can defeat the chariot brigades. The victorious horde can take what it wants from the defenseless settlement – food, wine, plate, and women. Rumors of the Dorian success might well have emboldened the Gasga to descend on Hattusas. Soon, all sorts of marginal people would have reached the decision to strike now and take their chances. No one had a plan. The motive everywhere was invidious, concupiscent, and bestially myopic. It stemmed from long-festering differences and capacities.

II. The Catastrophe amounted to vast spontaneous Jacquerie, whose sole aim consisted in satisfying the short-term lusts that motivate brawny clan-warriors. The pirates built nothing; they merely consumed and destroyed. Once their orgy had expended its zeal, the authors of it faded into the same chaotic background that their violence had generated. Laconia and Crete lapsed into Doric stasis. The Philistines, influenced by a formative segment of displaced Mycenaean aristos, imposed a gaudy conquistador order in the Levant, shortly to be challenged by the Israelites, whose exodus from Egypt and arrival in Canaan is probably an episode of the general disruption. A Levantine exodus established Carthage – literally, “The New City” – on the Tunisian coast; and evidence for Levantine activity in Sardinia and Sicily also exists for this time. A nucleus of Hittite elites left the burnt-out citadels and migrated into the Anatolian littoral. Here “Neo-Hittite” polities came into existence in the archaic period. The ruling class, like the Midas dynasty in Phrygia, became Hellenized on the Ionic pattern. Passages in Livy on The Roman Republic and elements of the Aeneas story, which is older by far than Virgil, together suggest that Mycenaean and Hittite refugees reached Italy and actively fostered novel polities in the early Iron Age of the peninsula. (See map)

Hesiod’s thematic insistence on “Envy,” “Strife,” or Eris (to give it its Greek name) in Works and Days fits what one could call Post-Catastrophic Ethics quite aptly. It is the poet’s initial topic. Two Erites exist, Hesiod opines: “One fosters evil war and battle, being cruel: her no man loves; but perforce, through the will of the deathless gods, men pay harsh Strife her honour due. But the other… stirs up even the shiftless to toil; for a man grows eager to work when he considers his neighbour, a rich man who hastens to plough and plant and put his house in good order; and neighbour vies with is neighbour as he hurries after wealth.”

Drews, writing in The End of the Bronze Age, can say moderately contradictory things about the Catastrophe. He narrates the destruction vividly, to be sure. He address the energetic dilapidation, however, in slightly misplaced teleological language: “In the long retrospect… the episode marked a beginning rather than an end, the ‘dawn of time’ in which people in Israel, Greece, and even Rome sought their origins.” Drews has some grounds for his assertion because, as he says, with the recovery after four hundred years came not only “alphabetic writing” but also “nationalism” and “republican political forms” along with “monotheism” and the life of the mind. The Catastrophe and the belated recovery, while not entirely separable, nevertheless consist of distinguishable events buffered from one another by an impressive block of four centuries. The moral lies in the annihilation.

Robbins, more sanguine in his view than Drews, describes post-Catastrophic Greece as “so impoverished, so lacking in material possessions, that archeologists have found little which would illuminate those times.” Drews remarks that: “Great buildings were not built, and houses were of the simplest sort, hardly more than huts.” Except in Attica, “pottery design and execution degenerated” and “there was no writing, even in the alphabetic script which came into Greece later.”

III. Antiquity’s greatest philosopher, Plato, seems to have been aware of the Catastrophe, echoes of which appear in the adjacent dialogues Timaeus and Critias, where we find the Atlantis story, and again in The Laws, with its story of the Cosmic Reversals.

The pedigree of the Atlantis story interested Plato almost as much as the story itself. In Timaeus, Critias, the teller of the tale, says that he heard it from his grandfather, also called Critias, who heard it from Solon, who had cast it in the form of a short epic poem; but Solon had a source prior to himself – certain Egyptian priests in a temple complex on the island of Saïs in the Nile Delta, where he had gone on a diplomatic and intelligence gathering mission as an envoy of the Athenian state. Wanting to impress the priests with his knowledge of the past, Solon began retailing stories about ancient events of his own nation, beginning with the story of the Deluge of Deucalion and Pyrrha. His priestly interlocutor interrupted him, saying, in Desmond Lee’s translation, “Oh Solon, Solon, you Greeks are all children, and there’s no such thing as an old Greek.” The priest adds that Greeks like Solon “have no belief rooted in old tradition and no knowledge hoary with age.” Solon registers wordless surprise. The priest continues:

There have been and will be many different calamities to destroy mankind, the greatest of them by fire and water, lesser ones by countless other means… There is at long intervals… widespread destruction by fire of things on earth… When on the other hand the gods purge the earth with a deluge, the herdsmen and those living in the mountains escape, but those living in the cities in your part of the world are swept… into the sea.

Later the priest comments on one invariant effect of the periodic calamities: “Writing and the other necessities of civilization have only just been developed when the periodic scourge of the deluge descends, and spares none but the unlettered and uncultured, so that you have to begin again like children.” Given the tendency of ancient discourse to confuse social and natural calamities, or to let natural metaphors refer to sociological events, this prologue to the Atlantis story and the story itself make sense as remote recollections of the human upheavals of the Catastrophe. “Deluge” can mean a human as well as a hydrological event. (“Après moi le deluge!”) The priest was right in his knowledge that the civilization that Solon represented was new and that it was largely unaware of the background to its own emergence. He was also right that the destruction of civilization, by whatever cause, entails the destruction also of literacy, therefore of record keeping, and therefore of archival and learned memory. He was right finally in his ascription of survival to those who live or who take refuge in the high country, as happened in Attica and in Cyprus.

In The Laws, the Stranger tells Socrates, represented as a young man, about the periodic bouleversements that afflict the cosmos. The cosmos has a rhythm of two phases. In one phase, God infuses the order of his Logos into things and sends the world careening away from him. At the inception of this phase, life conforms to a Golden Age, rather like Hesiod’s Cronian Age, when the first men lived happily under the tutelage of the chief Titan god. As the cosmos spins farther away from God, social conditions deteriorate until, in a calamitous moment, the direction of things reverses and the world starts its journey back towards God. At the instant of bouleversement, the second phase begins. First the influence of God ceases; next things fall apart, men are reduced to savagery, and they must struggle to rebuild orderly life all on their own. This fable operates at a higher level of abstraction than the Atlantis story, but once again at its core one confronts the philosophic sureness that nothing human goes on forever.

Consider the fragility and vulnerability of the existing Western civilization represented by North America and Europe (along with Australia and New Zealand) and to a degree by Japan and South Korea. (Let us include parts of South America.) People of this civilized dispensation necessarily awake each morning with the assumption that things will go on as they have, that the order remains stable, and that they may presume it as the background to their pursuit of happiness. Civilized order demands a measure of blitheness, hardly distinguishable from an attenuated faith, for its maintenance. The common man disdains prophets because he finds it difficult to differentiate prognosticators of doom from positively disposed agents of dissolution, seeming, as the prophets do, to call for changes in attitude and behavior that strike ordinary people as themselves corrosive of normality and habitude. Cassandra knows that Troy totters on the brink of fire and bloodletting but no one pays her the slightest attention.

Suspicion of disaster as a possibility sometimes succeeds in breaking through the outer shell of social complacency, but in curious self-disarming ways. The acute concern at the recent turn of the century over the “Y2K” computer-programming problem offers a case in point. All sorts of panic-stricken predictions hung on the belief that on 1 January 2000 every computer in the world would shut down causing the infrastructure of the industrial nations to grind to a halt. The “Global Warming” hysteria has something of the same character, with its predictions of a rising ocean inundating Florida and millions of people dying from heat stroke, as even the temperate zones become uninhabitable. To the list of doom-scenarios one could add fear of plague (AIDS, it used to be, or nowadays “bird flu”) or anxiety about a giant-meteor impact of “Dinosaur Killer” magnitude. Such apocalyptic fantasies characteristically elide the most probable cause of any impending systemic collapse of civilization.

IV. Men build civilization and men tear it down. They build it by intention, exertion, and discipline, under an image of order. They tear it down by acts of casual omission as much as by acts of concupiscent aggression and destruction. Omission and aggression can operate in synchronization to destroy a society. Civilization indeed carries with it many of the causes of its own gradual declension. In the achievement of widespread and sustained security, for example, the likelihood that the beneficiary generation will fail to appreciate the formative insights of the benefactor generation runs high. Complacency results. The beneficiary generation then fails in the obligation to maintain the basis of security, institutional, economic, military or otherwise. It can embrace novel “theories” that titillate through being exotic in their vocabulary and counterintuitive in their implications and which, being incompatible with received lore, undermine that lore and weaken the cultural health. The society is too busy “having fun” to reflect on its situation. In the succession of the beneficiary generation, once again, an Oedipal contempt for the benefactor generation can develop, which seriously distorts the concept of reality of the beneficiaries.

A delusory independence from ancestral exertion invariably expresses itself in the spurious rebuke of received authority. In Odyssey, Homer sharply contrasts Odysseus’ hard-won capacity for self-restraint with the suitors’ concupiscent impulsiveness – their mindless enthrallment to their own grossest appetites. The same difference marks Odysseus off from his crewmates, all of whom succumb to their lack of any appetitive brakes leaving the king to return to his kingdom alone. The suitors, who are a beneficiary generation par excellence, treat law and custom with disdain. In a speech, Telemachus makes the prediction that, unless checked, the suitors’ arrogance will spread through all of Ithaca and wreck the society.

It lies in the logic of Homer’s story, that, had Odysseus not returned home and had one of the suitors indeed become the technical husband of Penelope and therefore the nominal king in Ithaca – the exegesis would nevertheless not have found its terminus. The remaining disappointed suitors would have besieged the lucky victor and done away with him, and so on, not quite ad infinitum. One human trait that restraint restrains, after all, is envy, resentment, or what Hesiod calls destructive Strife, and which he sees as the perpetual corruptor of social order.

In its complacent self-absorption, a beneficiary generation can become flagrant in the ostentation of its affluence. It can come to regard itself as naturally endowed with permanence in its status and as possessing a kind of invulnerability to threat rather than as having direct responsibility for the maintenance of its own welfare. Such ostentation provokes renewed resentment – first among the internal proletariat that exists in every society and second among the various external proletariats that gaze into affluence from the impoverished yonder side of the frontier. This is not a matter of justification, but of imitation, as inflamed desire transforms itself into a practical if thoughtless intention to acquire by any means what others flaunt as their entitled portion of enjoyment. In a legal sense, the inheritors of wealth have an absolute right to it whereas the bandits who scheme to take it for their own have absolutely none.

Should the constabulary catch the bandits in actu, then the bandits can only expect to be shut away, sent to forced labor, or even strung up in the town square. This will all be entirely correct, as the French say, and not simply from the civic perspective. A mass of bandits will, however, exceed the ability of the constabulary to respond. “Behold, the enemy’s ships came (here); my cities (?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country,” wrote the Ugaritic king.

If the affluent society should begin to federate members of the external proletariat for unskilled labor or military service, as the Bronze Age kingdoms seem to have done with the Shardana and the Shekelesh and as the Roman Empire did with the Gothic barbarians, then the internal and external proletariats can arrive at a sense of a common grudge and, however dimly perceived, of a common cause. The avarice of the proletariat can grow stronger than the commitment of the civic classes to their own preservation. As one fits aspects of Homeric and Hesiodic sociology into what is known historically and archeologically about the Catastrophe one sees that something like this process must have occurred in a great boiling-over three thousand years ago in the region comprising Greece, Anatolia, the islands, and the Levant. The Catastrophe, says Drews, was worse than the fall of the Western Empire.

So that there might be order in the polity, Plato constantly argued, there must first be order in the individual soul. Restraint and askesis play essential roles in the orderliness of the soul – hence also in civic arrangements. Restraint acknowledges the sacredness of persons and property and askesis honors the wisdom not to flaunt affluence – not because one is not entitled to it either as the fruits of personal productivity or as inheritance, but because it is anthropologically foolhardy to do so. Ours is an age of fantastically inflated, pathologically ostentatious economies; quite without cosmic calamities it is also an age rapidly losing its historical memory and even its literacy. There is a voluntary relinquishment of intellectual and moral rigors for the sake of paltry divertissement. Too many modern people see in their electronic conveniences, in their false freedom from anxiety and care, what the guardians of Mycenae must have seen in their Cyclopean walls and defensive ditches: untouchable superiority and immunity from annoyance.

Our electronification, our material flagrancy, and our sense of rightful endowment likely render us more, not less, vulnerable than ancient peoples to sudden unforeseen catastrophes whose occasion might simply lie in a power failure but whose form (or rather formlessness) will be greed and rapacity at their rawest and whose story will be one of the precipitous collapse of those institutions that, despite our delinquency or our contempt, formerly protected us from “evil things.”

Europe is headed for another calamity.

Interesting article, thanks

And don’t forget “A Canticle For Leibowitz”

So that there might be order in the polity, Plato constantly argued, there must first be order in the individual soul. Restraint and askesis play essential roles in the orderliness of the soul – hence also in civic arrangements. Restraint acknowledges the sacredness of persons and property and askesis honors the wisdom not to flaunt affluence – not because one is not entitled to it either as the fruits of personal productivity or as inheritance, but because it is anthropologically foolhardy to do so. Ours is an age of fantastically inflated, pathologically ostentatious economies; quite without cosmic calamities it is also an age rapidly losing its historical memory and even its literacy. There is a voluntary relinquishment of intellectual and moral rigors for the sake of paltry divertissement. Too many modern people see in their electronic conveniences, in their false freedom from anxiety and care, what the guardians of Mycenae must have seen in their Cyclopean walls and defensive ditches: untouchable superiority and immunity from annoyance.This is the understanding that underscored the wisdom of America's founders; this is also the understanding that so many of us have cast aside in favor of our toys and amusements. I have said that God will not save that upon which so many of us have turned our backs. There is a price to be paid forthat, and it will consume the innocwent abd guilty alike.

The author of this essay points out that all civilizations fail in the end. Some through conquest, but for many it was simple exhaustion and IGNORance of the values that once invigorated them. We have no special dispensation.

This author uses an impressive vocabulary and a scholarly approach to tell us wht many of us are now coming to realize: Something Wicked This Way Comes. And it is not the old Soviet barbarian, the Islamic homicidal bomber or the Chinese cultural hegemonist - rather, it is the collapse of our own Western civilization chiefly due to our own weakness. It may not yet be too late to turn the tide, but the issue at stake is so much larger than perhaps any of us realize. This essay is a jaw-dropper, for it is a crucial pieceof the puzzle slotting into place.

Neither geological nor climatological but rather sociological in characterThanks Nikas777.

|

||

| · join · view topics · view or post blog · bookmark · post new topic · subscribe · | ||

|

|

|||

Gods |

Thanks Nikas777.It left cities in smoking ruin, their wealth plundered; it plunged the affected regions into a Dark Age, bereft of literacy, during which populations drastically shrank while the level of material culture reverted to that of a Stone Age village.The author mildly overstates his case. :') |

||

|

· Discover · Nat Geographic · Texas AM Anthro News · Yahoo Anthro & Archaeo · Google · · The Archaeology Channel · Excerpt, or Link only? · cgk's list of ping lists · |

|||

'The Truth Is Out There'...and as soon as I find some way to contact him I will send him a link to EARTH IN UPHEAVAL.

Ping for later.

The blow-out of Thera destroyed the Minoans but it didn’t bring about the end of the Bronze Age. What’s important to realize about Thera was that it was a crater with an island in the center before the Bronze Age eruption, not a mountain, with limited access from the sea creating the perfect sheltered harbor. The Minoans essentially build their Hong Kong right on top of an active volcano on the island in the middle.

The cause of the Catastrophe as described is similar to the Fall of Rome—various barbarian people driven by a particularly vicious tribe, e.g. the Huns. A difference was the Church preserving knowledge and civility -— there was no equivalent in the Catastrophe.

“...It left cities in smoking ruin, their wealth plundered; it plunged the affected regions into a Dark Age, bereft of literacy, during which populations drastically shrank while the level of material culture reverted to that of a Stone Age village. Echoes of the event – or complicated network of linked events – turn up in myth and find reflection in early Greek literature. The Trojan War appears to be implicated in this event, as do certain episodes of the Old Testament. Recovered records hint at this massive upheaval:

http://www.geocities.com/regkeith/linkipuwer.htm PAPYRUS IPUWER

Egypt in Upheaval

The Papyrus Ipuwer is not a collection of proverbs... or riddles; no more is it a literary prophecy... or an admonition concerning profound social changes. It is the Egyptian version of a great catastrophe.

The papyrus is a script of lamentations, a description of ruin and horror.

PAPYRUS 2:8 Forsooth, the land turns round as does a potter’s wheel.

2:11 The towns are destroyed. Upper Egypt has become dry (wastes?).

3:13 All is ruin!

7:4 The residence is overturned in a minute.

4:2 ... Years of noise. There is no end to noise.

What do “noise” and “years of noise” denote? The translator wrote: “There is clearly some play upon the word hrw (noise) here, the point of which is to us obscure.” Does it mean “earthquake” and “years of earthquake”? In Hebrew the word raash signifies “noise”, “commotion”, as well as “earthquake”. Earthquakes are often accompanied by loud sounds, subterranean rumbling and roaring, and this acoustic phenomenon gives the name to the upheaval itself.

Apparently the shaking returned again and again, and the country was reduced to ruins, the state went into sudden decline, and life became unbearable.

Ipuwer says:

PAPYRUS 6:1 Oh, that the earth would cease from noise, and tumult (uproar) be no more.

The noise and the tumult were produced by the earth. The royal residence would be overthrown “in a minute” and left in ruins....

The papyrus of Ipuwer contains evidence of some natural cataclysm accompanied by earthquakes and bears witness to the appearance of things as they happened at that time.

I shall compare some passages from the Book of Exodus and from the papyrus. As, prior to the publication of Worlds in Collision and Ages in Chaos, no parallels had been drawn between the Bible and the text of the Papyrus Ipuwer, the translator of the papyrus could not have been influenced by a desire to make his translation resemble the biblical text.

PAPYRUS 2:5-6 Plague is throughout the land. Blood is everywhere.

EXODUS 7:21 ... there was blood thoughout all the land of Egypt.

This was the first plague.

PAPYRUS 2:10 The river is blood.

EXODUS 7:20 ... all the waters that were in the river were turned to blood.

This water was loathsome, and the people could not drink it.

PAPYRUS 2:10 Men shrink from tasting — human beings, and thirst after water.

EXODUS 7:24 And all the Egyptians digged round about the river for water to drink; for they could not drink of the water of the river.

The fish in the lakes and the river died, and worms, insects, and reptiles bred prolifically.

EXODUS 7:21 ... and the river stank.

PAPYRUS 3:10-13 That is our water! That is our happiness! What shall we do in respect thereof? All is ruin!

The destruction in the fields is related in these words:

EXODUS 9:25 ... and the hail smote every herb of the field, and brake every tree of the field.

PAPYRUS 4:14 Trees are destroyed.

6:1 No fruit nor herbs are found..

This portent was accompanied by consuming fire. Fire spread all over the land.

EXODUS 9:23-24 ... the fire ran along the ground.... there was hail, and fire mingled with the hail, very grievous.

PAPYRUS 2:10 Forsooth, gates, columns and walls are consumed by fire.

The fire which consumed the land was not spread by human hand but fell from the skies.

By this torrent of destruction, according to Exodus,

EXODUS 9:31-32 ... the flax and the barley was smitten; for the barley was in the ear, and the flax was boiled. But the wheat and the rye were not smitten: for they were not grown up.

It was after the next plague that the fields became utterly barren. Like the Book of Exodus (9:31-32 and 10:15), the papyrus relates that no duty could be rendered to the crown for wheat and barley; and as in Exodus 7:21 (”And the fish that was in the river died”), there was no fish for the royal storehouse.

PAPYRUS 10:3-6 Lower Egypt weeps... The entire palace is without its revenues. To it belong (by right) wheat and barley, geese and fish.

The fields were entirely devastated.

EXODUS 10:15 ... there remained not any green thing in the trees, or in the herbs of the fields, through all the land of Egypt.

PAPYRUS 6:3 Forsooth, grain has perished on every side.

5:12 Forsooth, that has perished which yesterday was seen. The land is left over to its weariness like the cutting of flax.

The statement that the crops of the fields were destroyed in a single day (”which yesterday was seen”) excludes drought, the usual cause of a bad harvest; only hail, fire, or locusts could have left the fields as though after “the cutting of flax”. The plague is described in Psalms 105:34-35 in these words: “... the locusts came, and caterpillars, and that without number. And did eat up all the herbs in their land, and devoured the fruit of their ground.”

PAPYRUS 6:1 No fruit nor herbs are found... hunger.

The cattle were in a pitiful condition.

EXODUS 9:3 ... the hand of the Lord is upon the cattle which is in the field... there shall be a very grievous murrain.

PAPYRUS 5:5 All animals, their hearts weep. Cattle moan....

Hail and fire made the frightened cattle flee.

EXODUS 9:19 .. gather thy cattle, and all that thou hast in the field...

21 And he that regarded not the word of the Lord left his servants and his cattle in the field.

PAPYRUS 9:2-3 Behold, cattle are left to stray, and there is none to gather them together. Each man fetches for himself those that are branded with his name.

The ninth plague, according to the Book of Exodus, covered Egypt with profound darkness.

EXODUS 10:22 ... and there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt.

PAPYRUS 9:11 The land is not light....

“Not light” is in Egyptian equivalent to “without light” or “dark”. But there is some question as to whether the two sentences are entirely parallel. The years of wandering in the desert are described as spent in gloom under a cover of thick clouds....

The Last Night before the Exodus

According to the Book of Exodus, the last night the Israelites were in Egypt was a night in which death struck instantly and took victims from every Egyptian home. The death of so many in a single night, even at the same hour of midnight, cannot be explained by a pestilence, which would last more than a single hour. The story of the last plague does seem like a myth; it is a stranger in the sequence of the other plagues, which can be explained...

...Apparently we have before us the testimony of an Egyptian witness of the plagues.

On careful reading of the papyrus, it appeared that the slaves were still in Egypt when at least one great shock occurred, ruining houses and destroying life and fortune. It precipitated a general flight of the population from the cities, while the other plagues probably drove them from the country into the cities.

The biblical testimony was reread. It became evident that it had not neglected this most conspicuous event: it was the tenth plague.

In the papyrus it is said: “The residence is overturned in a minute.” On a previous page it was stressed that only an earthquake could have overturned and ruined the royal residence in a minute. Sudden and simultaneous death could be inflicted on many....

EXODUS 12:30 And Pharaoh rose up in the night, he, and all his servants, and all the Egyptians; and there was a great cry in Egypt: for there was not a house where there was not one dead.

A great part of the people lost their lives in one violent shock. Houses were struck a furious blow.

EXODUS 12:27 [The Angel of the Lord] passed over the houses of the children of Israel in Egypt, when he smote the Egyptians, and delivered our houses.

The word nogaf for “smote” is used for a violent blow, e.g. for thrusting with his horns by an ox.

The residence of the king and the palaces of the rich were tossed to the ground, and with them the houses of the common people and the dungeons of captives.

EXODUS 12:29 And it came to pass, that at midnight the Lord smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh that sat on his throne unto the firstborn of the captive that was in the dungeon.

PAPYRUS 4:3, and 5:6 Forsooth, the children of princes are dashed against the walls.

6:12 Forsooth, the children of princes are cast out in the streets.

PAPYRUS 6:3 The prison is ruined.

2:13 He who places his brother in the ground is everywhere.

To it correspond Exodus 12:30:

... there was not a house where there was not one dead.

In Exodus 12:30 it is written:

... there was a great cry in Egypt.

To it corresponds the papyrus 3:14:

It is groaning that is throughout the land, mingled with lamentations.

The statues of the gods fell and broke in pieces: “this night... against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgment” (Exodus 12:12).

A book by Artapanus, no longer extant, which quoted some unknown ancient source and which in its turn was quoted by Eusebius, tells of “hail and earthquake by night [of the last plague], so that those who fled from the earthquake were killed by the hail, and those who sought shelter from the hail were destroyed by the earthquake. And at that time all the houses fell in, and most of the temples.”

The earth was equally pitiless towards the dead in their graves: the sepulchers opened, and the buried were disentombed.

PAPYRUS 4:4, also 6:14 Forsooth, those who were in the place of embalmment are laid on the high ground.

Revolt and Flight

The description of distrubances in the Papyrus Ipurew, when compared with the scriptural narrative, gives a strong impression that both sources relate the very same events. It is therefore only natural to look for mention of revolt among the population, of a flight of wretched slaves from this country visited by disaster, and of a cataclysm in which the pharaoh perished.

Although in the mutilated papyrus there is no explicit reference to the Israelites or their leaders, three facts are clearly described as consequences of the upheaval: the population revolted; the wretched or the poor men fled; the king perished under unusual circumstances....

PAPYRUS 4:2 Forsooth, great and small say: I wish I might die.

5:14f. Would that there might be an end of men, no conception, no birth! Oh, that the earth would cease from noise, and tumult be no more!

The escaped slaves hurried across the border of the country. By day a column of smoke went before them in the sky; by night it was a pillar of fire.

EXODUS 13:21 ... by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way; and by night in a pillar of fire, to give them light; to go by day and night.

PAPYRUS 7:1 Behold, the fire has mounted up on high. Its burning goes forth against the enemies of the land.

The translator added this remark: “Here the ‘fire’ is regarded as something disastrous.”

After the first manifestations of the protracted cataclysm the Egyptians tried to bring order into the land. They traced the route of the escaped slaves. The wanderers became “entangled in the land, the wilderness hath shut them in” (Exodus 14:3). They turned to the sea, they stood at Pi-ha-Khiroth. “The Egyptians pursued after them. The Egyptians marched after them.” A hurricane blew all the night and the sea fled.

In a great avalanche of water “the sea returned to his strength”, and “the Egyptians fled against it”. The sea engulfed the chariots and the horsemen, the pharoah and all his host.

The Papyrus Ipuwer (7:1-2) records only that the pharaoh was lost under unusual circumstances “that have never happened before”. The Egyptian wrote his lamentations, and even in the broken lines they are perceptible:

... weep... the earth is... on every side... weep...

Excerpt from Ages in Chaos, by Immanuel Velikovsky (pages 18-31)

To this day, scholarly explanations for the collapse of the great Egyptian Empire, a civilization that burst on to History’s stage... arrayed in wisdom beyond our Centuries... that one day was... and then suddenly was not... most explanations remain woefully inadequate

Thank the gods and heroes that such decadent and boorish behavior never occured at the end of the Stone Age, when copper & bronze were discovered, and only used for peaceful and benevolent purposes!

Calling the start of the Iron Age "The Catastrophe" beggars belief. Spoken like true Luddites, still worshipping at the feet of The Noble Savage, denouncinging that most evil of all evils, the Mother Gaea raping iron plow.

My hat is off to any thinking person who can stand reading both Part I and Part II in their entirity, without gagging: they get the Iron Stomach Award with Bronze Cluster.

:’) I think he’s too far gone. The only reason a catastrophe is believed to have happened, a dark age, is because of the screwed up conventional pseudochronology.

Thanks.

You missed the point. You should read further.

I agree completely. Say what one will about the Soviet communist, the Islamic fundie, the Han supremacist -- at least they still believe in something. Here in the West, all we believe in is our own nerve endings.

In the end, they hate us for who we are and what we represent, and they want us all dead. You can't reason with the plague; you can't negotiate with cancer. You must destroy it. Because the alternative is...

Great article. Thanks for posting it. FreeRepublic rocks!

It is interesting to note that Plato’s (Solon’s) story of the location of Atlantis clearly refers to the existence of true continents to the west of the island. The explicit description of the island being beyond the Pillars of Hercules tells me that it was not Thera. Nor does the description of its end jibe with a massive volcanic eruption as occurred at Santorini.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.